John Baldessari, radically influential Conceptual artist, dies at 88

- Share via

For the record:

5:24 p.m. Jan. 5, 2020An earlier version of this article misstated the day Baldessari died. It was Thursday, not Saturday.

In 1970, Los Angeles artist John Baldessari was ready to take his work in a new direction, so he gathered up paintings he made between 1953 and 1966, brought them to a mortuary and had them cremated — the remains laid to rest in an urn for what would eventually be called “Cremation Project.”

Even in the act of destruction, Baldessari was a man of creation.

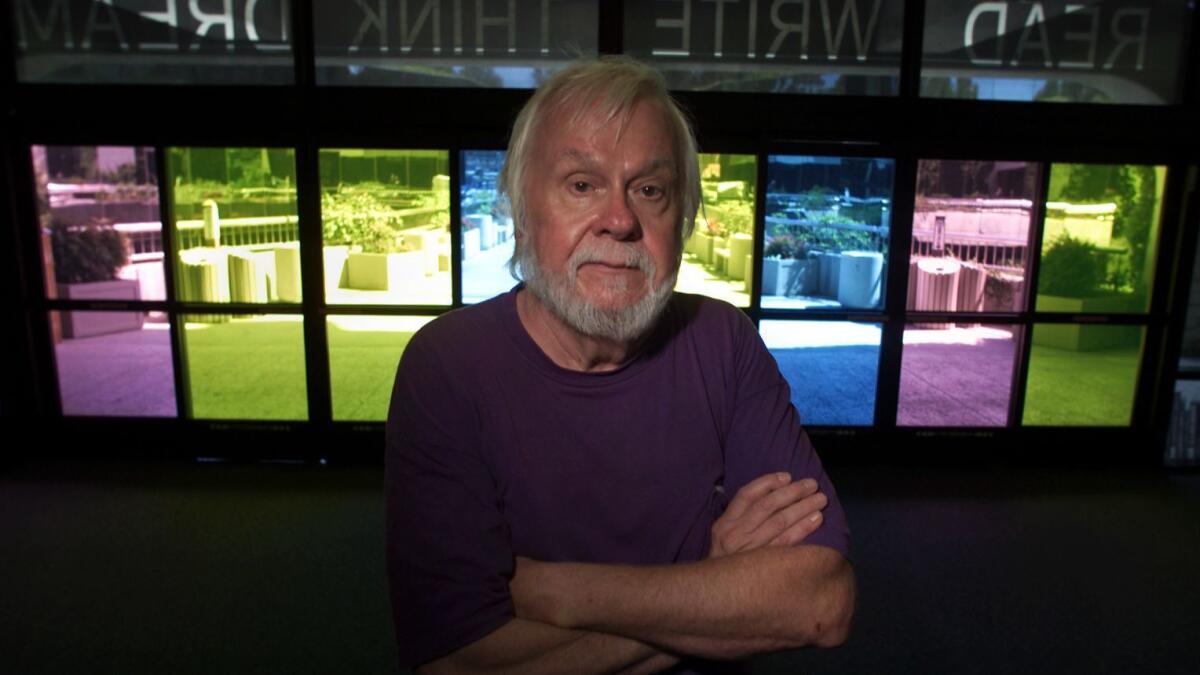

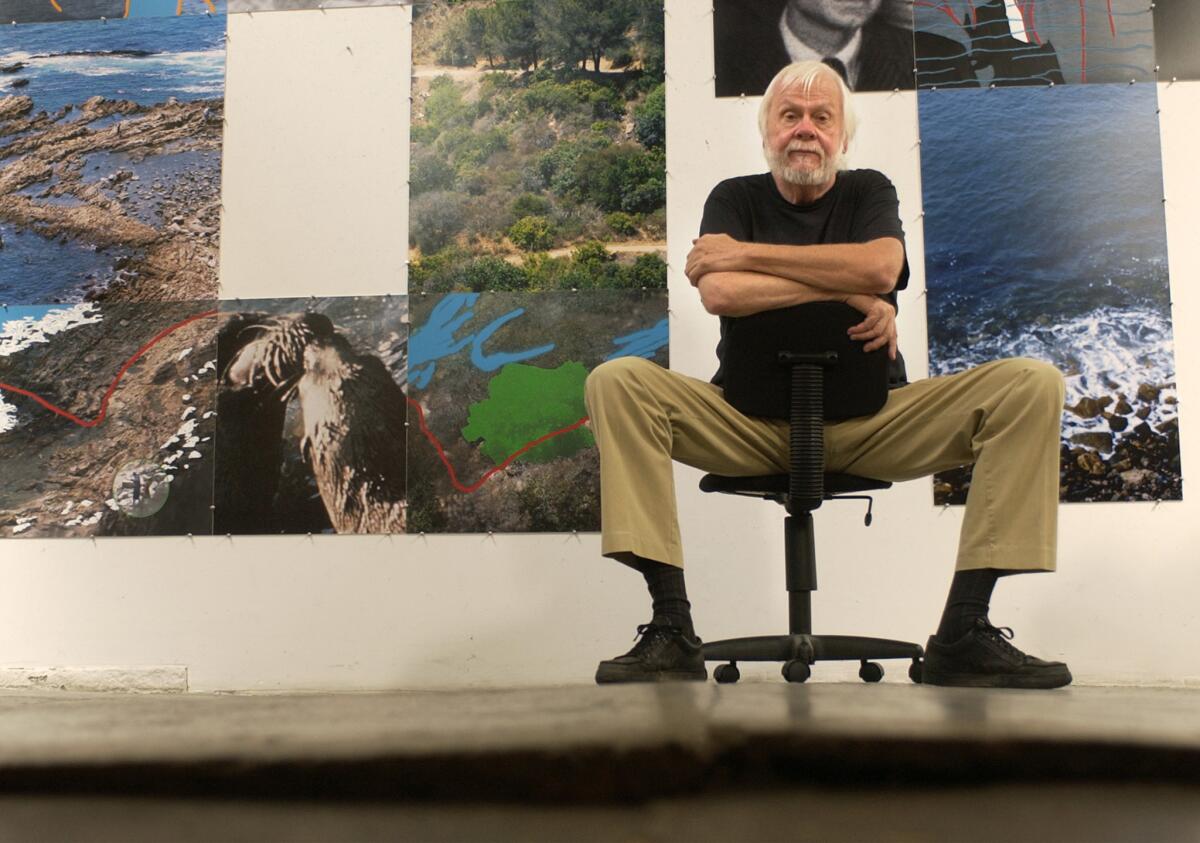

Forty-seven years later, when The Times visited the 85-year-old artist in his L.A. studio, Baldessari was in the midst of no fewer than five new series of works, with a survey exhibition of sculptural prints opening soon at the L.A. studio Mixografia and a retrospective on the horizon at the Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

This seemingly tireless spirit — a gentle giant of Conceptual art whose irreverent questions about the nature of art brought him international acclaim and shaped a generation of younger talent — died in his sleep Thursday at 88. The death was confirmed Sunday by Baldessari’s foundation and by Margo Leavin, his former Los Angeles art dealer.

Baldessari was known as a mild-mannered leader who spoke softly but with an abundance of human insight and droll wit. The 6-foot-7-inch artist towered over most of his students at CalArts, UCLA and UC San Diego, as he did over an art movement that valued ideas more than objects. His height enticed writers to describe him in physical terms, including “a cross between Walt Whitman and a redwood tree” (the Christian Science Monitor). But Baldessari was a thinker who called himself “a hybrid between a formalist and a moralist.”

Inspired by the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, who overturned traditional definitions of art in the early 20th century, and by L.A. artist Edward Ruscha’s imaginative combinations of pictures and words, Baldessari explored language and mass media culture in text-and-image paintings and photo compositions derived from film stills, magazines and other sources.

In a review of Baldessari’s 2010 retrospective exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Times art critic Christopher Knight deemed him “arguably America’s most influential Conceptual artist.”

“John Baldessari has worked in the gap between paintings and camera images for the last 45 years,” Knight wrote, noting that “his marvelous rummaging around in that fissure” demonstrated that the gap was fertile territory and “often a strange and funny place to be.”

The LACMA exhibition, “Pure Beauty,” opened at the Tate Modern in London and later traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The show took its name from a 1966-68 painting with those words boldly painted in black across the center of a plain white canvas. Another early painting resembles a page from a how-to book for beginning photographers. A grainy photographic image of Baldessari standing in front of a palm that appears to sprout from his head is underscored by the word “wrong.” In both paintings, the lettering is the work of a commercial sign painter hired by the artist.

Commenting on “Wrong” in a Village Voice review, critic Peter Schjeldahl dubbed Baldessari “a poet of the wrongness that aesthetic devotion visits upon flawed, shaggy, mere individuality. He repeatedly evokes the experience … of feeling devalued by what one loves: just not good enough, unworthy, even fraudulent. This is an embittering experience for many. Baldessari absorbs it with consummate humor.”

When composing works of multiple images, the artist likened his task to that of writers of detective fiction or poetry who build an “architecture of meaning” by juxtaposing disparate elements.

Despite awards and honors throughout his long career — including a 2018 guest appearance on “The Simpsons” — Baldessari retained his humility.

“I feel fortunate. Somebody’s paying attention,” he said in an interview with The Times in 2017. “I’m grateful to be influential around the world. People look at what I do. I can’t ask for more than that.”

Still, he grew disillusioned by the art world and worried about the corruption of money. When he began his career, he said in 2012, there was no expectation of becoming wealthy. “You did it because you believed in it. It wasn’t about money. Now, it’s all about money.”

Born June 17, 1931, in National City, Calif., near San Diego, John Anthony Baldessari was the son of Antonio Baldessari, a salvage dealer, and his wife, Hedvig. Baldessari showed interest in the arts as a young boy. His schoolteachers acknowledged his natural artistic abilities, often picking him to do murals and special projects. That recognition gave him the courage to pursue art, although his father worried it wasn’t a financially practical career.

Baldessari received a master’s degree in art in 1957 from what is now San Diego State University and taught art classes in San Diego-area public schools before landing a position as an assistant professor of art at San Diego State.

I set out to right all the things wrong with my own art education. But I found that you can’t really teach art, you can just sort of set the stage for it.

— John Baldessari

“I’ve taught all my life,” he told San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker in 2003. “Everything from grade school to college to juvenile delinquents. I set out to right all the things wrong with my own art education. But I found that you can’t really teach art, you can just sort of set the stage for it.”

Baldessari moved to Los Angeles and set up CalArts’ post-studio art course, which he described as “all the kind of art you didn’t need a studio to deal with.”

He continued to teach at CalArts as his career took off and later joined the faculty at UCLA, building a legacy of painters, sculptors, photographers and installation artists who were inspired by his work but found their own direction. Among his best-known students were Mike Kelley, David Salle, Matt Mullican, Barbara Bloom, Meg Cranston, Tony Oursler, Liz Craft and, more recently, Analia Saban.

Salle, Baldessari’s student at CalArts from 1971 to 1975, developed a friendship with his professor and came to know him as someone who was “immensely understanding of human predicament and what’s involved in being an artist.” He remembered him as having worn his “enormous acclaim very lightly.”

Baldessari, he said, brought new meanings to visual art that diverged from the traditions of painting and sculpture. “He gave form to a kind of linguistic, poetical way of representing the world that looks simple but is not.”

Cranston, who graduated from CalArts in 1986 and knew Baldessari for more than 30 years, said she was inspired by her professor’s curiosity about the world around him. He taught her that “I could do whatever I wanted to do ... to always have a plan and to keep it simple.” Baldessari, she said, broadened what was possible in art.

His impact while at CalArts was never forgotten. The John Baldessari Art Studio Building opened in 2013 for students and faculty in recognition of his years teaching there.

Baldessari also branched out into curatorial, installation and design work at museums. Particularly active at LACMA, he designed a logo, banners for the Wilshire Boulevard facade and a wildly popular installation of Belgian Surrealist Rene Magritte’s work that covered the floor with a sky-like carpet and the ceiling with freeway images.

His work has been shown in the Venice Biennial in Italy, the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, the Whitney Biennial in New York and Documenta in Kassel, Germany. Retrospective exhibitions of his work have appeared at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, where he served on the board of trustees, as well as at the Kunsthaus Graz in Austria and at Mumok, the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, also in Austria.

Baldessari’s work is in the collections of LACMA, MOCA and the Broad in Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney in New York. He exhibited his work in L.A. for nearly three decades at Leavin’s, which closed to the public in 2012; he began showing with Sprüth Magers gallery when it opened an L.A. outpost in 2016, and he’s represented by Marian Goodman Gallery in New York.

Baldessari was honored at MOCA’s annual gala in 2015, during which museum director Philippe Vergne told the crowd that Baldessari was “someone who’s been an inspiration, a teacher, a friend, a leader for many of us. And for us at MOCA, he’s a marvelous board member, a board member who tells it like it is — and God knows we need that.”

Speaking to Baldessari’s prolific output, Vergne added: “He’s someone who’s had over 377 solo exhibitions, been part of more than 1,500 group exhibitions, who has produced over 4,000 works of art.”

President Obama presented Baldessari with the National Medal of Arts in 2015 — another sign of the artist’s broad influence on culture.

A Baldessari quote was used in a 2013 arts education campaign: “Learn to dream” appeared on bus signs, billboards and Metro buses redesigned to look like traditional school buses across Los Angeles, all to spark conversations about the importance of arts education.

Baldessari was among the earliest artists to engage with image culture and the onslaught of mass media, said Lisa Wainwright, professor of art history, theory and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He pushed the notion that “the idea that generates the work is the key to the work, not the craft” and that art and art schools were “the last bastions of democratic thinking.”

But his legacy, she said, extends beyond his art; his work as an educator was just as influential.

“He had the idea that art school is about free play, that it’s about unfettered experimentation that issues creative propositions. ... Everything was possible and anything goes.”

More succinctly, Baldessari was radical, Wainwright said. “He poked at the art world. He poked at institutions. He was unafraid and irreverent and playful ... and he was committed to teaching. ”

Times art critic Christopher Knight contributed to this article.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.