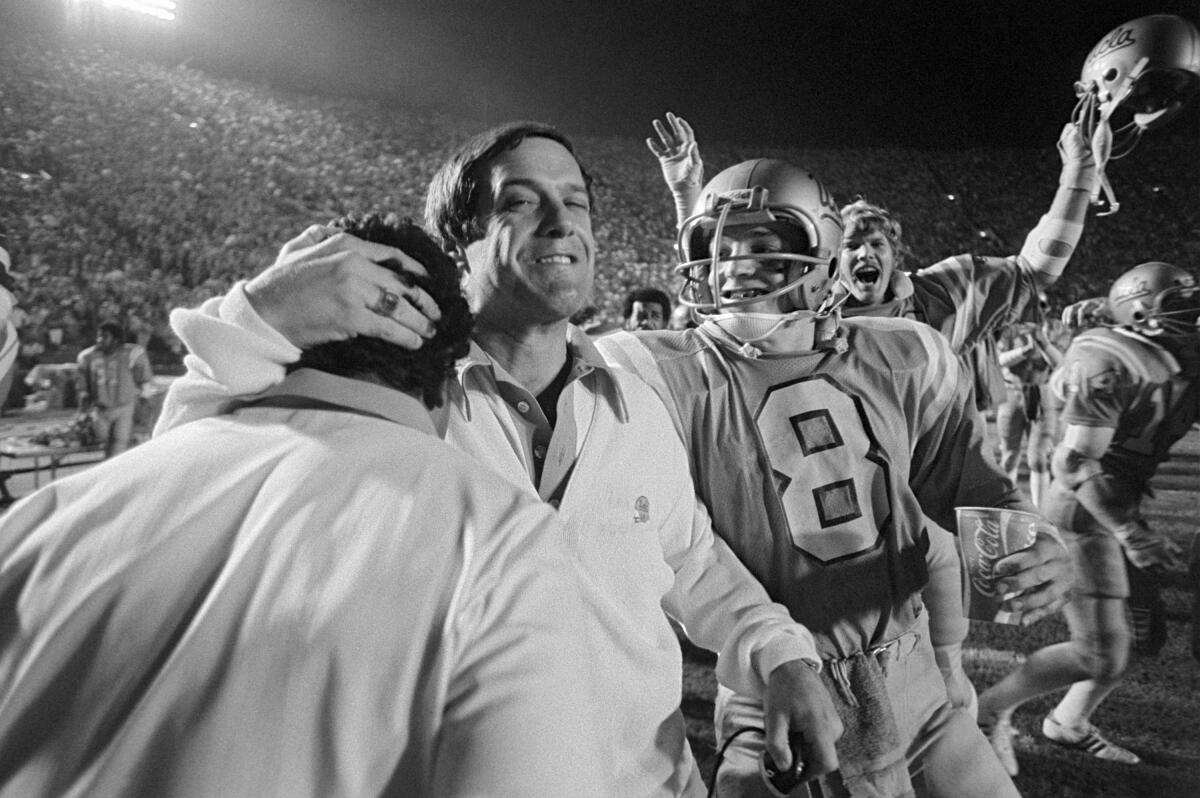

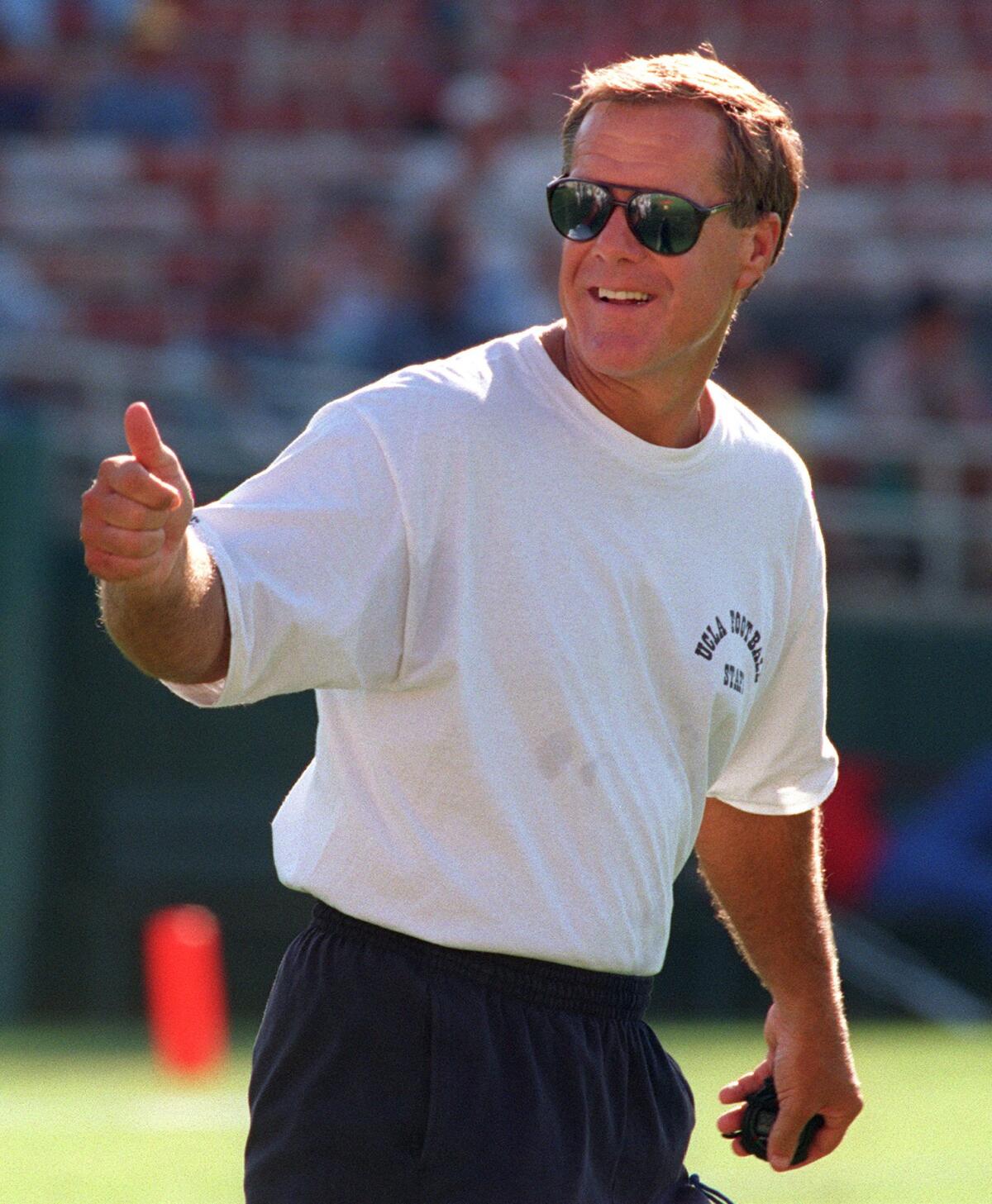

Terry Donahue, the winningest coach in UCLA football history, dies at 77

- Share via

Terry Donahue won more football games at UCLA than any other coach, establishing a blue-and-gold standard for sustained success over his 20 seasons at the school.

None of it would have been possible without what might have been his two greatest triumphs: getting to play for and coach the Bruins.

As an undersized defensive tackle initially passed over by the school, prompting stops at San Jose State and L.A. Valley College, he went from designated practice tackling dummy to two-year starter and member of the school’s first Rose Bowl championship team.

As a coach, he rose from an untested 31-year-old to universally esteemed veteran, his 151 victories more than doubling the total of anyone else in school history. His 98 Pacific 10 victories still stand as the most in conference history.

Donahue, the perpetually tanned, self-effacing and seemingly ageless coach who guided the Bruins to their longest run of football glory under a single coach, died Sunday evening at his home in Newport Beach surrounded by family after a two-year battle with cancer, the school announced. He was 77.

UCLA had announced in May 2019 that Donahue underwent surgery for an undisclosed form of cancer and was beginning chemotherapy. Donahue is survived by his wife Andrea and three daughters, Nicole, Michele and Jennifer, in addition to three sons-in-law and 10 grandchildren.

Under Donahue, UCLA won four Pac-10 championships and tied for another. Donahue became the first coach to win a bowl game in seven straight seasons, and his teams finished ranked in the top 10 nationally five times.

It was a dizzying run of prosperity for someone whose humble beginnings in the sport briefly caused him to contemplate a career as a boxer.

“I am an overachiever,” Donahue said after going 9-2-1 in 1976 during his first season as UCLA’s head coach, “and very, very … ah, average. Actually, ‘sorry’ is probably the word I’m searching for.”

Donahue’s teams were anything but pathetic. In his first game as coach, the Bruins upset third-ranked Arizona State and legendary Sun Devils coach Frank Kush, 28-10, in Tempe, Ariz., but only after Pepper Rodgers, Donahue’s UCLA predecessor, soothed the antsy rookie coach.

Ed O’Bannon Jr. spearheaded the NCAA’s name, image and likeness movement but says in a first-person piece for the Los Angeles Times that ‘the baton has been passed.’

“Donahoo,” Rodgers said, purposefully teasing his protégé with the mispronunciation, “you and Kush aren’t playing. Your players are.”

Donahue routinely got the better of the Pac-10’s top coaches, including Washington’s Don James and USC’s John Robinson. Donahue won his last five games against the Trojans, part of a UCLA-record streak of dominance in the rivalry that eventually reached eight games under successor Bob Toledo.

Donahue’s early UCLA teams were known for a plodding, ground-oriented attack that won games, not to mention a legion of critics over what was derided as an overly conservative approach.

But after the Bruins went 5-6 in 1979, Donahue decided that some of the criticism was warranted. He hired Homer Smith, a Harvard-educated offensive coordinator who brought with him an aerial attack that accentuated the talents of quarterbacks Troy Aikman, Steve Bono, Jay Schroeder, Tommy Maddox and Tom Ramsey. UCLA blended in a sprinkling of trick plays, especially against teams considered superior in talent, to stunning results.

The Bruins went 9-2 in 1980 but were ineligible for a bowl game because of academic improprieties. The following season started a run of eight consecutive bowl berths that ended with seven straight victories, including four in a row on New Year’s Day. UCLA won the 1983 and ’84 Rose Bowls, the ’85 Fiesta Bowl, the ’86 Rose Bowl, the ’86 Freedom Bowl, the ’87 Aloha Bowl and the ’89 Cotton Bowl.

“He was an amazing man,” said Scott Altenberg, who played for Donahue long after his father, Kurt, caught the game-winning touchdown to beat USC as Donahue’s teammate in 1965 as part of a Bruins team that went on to win the Rose Bowl. “A Bruin to the end.”

Donahue finished his UCLA career with a 151-74-8 record, not to mention some regrets after what was widely considered a premature retirement in December 1995. While he publicly vacillated about his future, some Bruins players figured Donahue had provided a tipoff when he participated in the team’s season-ending ritual of jumping over a wall after the final practice.

But on the day that Donahue was set to announce his plans, uncertainty lingered. Marc Dellins, UCLA’s sports information director, prepared two news releases, one saying Donahue would leave and another saying he would stay. Not until the words left Donahue’s mouth that he was retiring to take a broadcasting job with CBS was his decision official.

He later acknowledged it was the wrong choice.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that I quit too early,” Donahue told the Los Angeles Daily News in 2015, alluding to unspecified differences with UCLA athletic officials that he said hindered his effectiveness and led to his departure.

Born on June 24, 1944 in Los Angeles, Donahue grew up as one of five brothers in North Hollywood. He played football at Sherman Oaks Notre Dame High but was not a coveted prospect, leading to one unhappy season as a walk-on at San Jose State.

Donahue returned home to Southern California and put his pugnacious streak to use — as a boxer.

He won an amateur bout in a long-shuttered San Fernando Valley arena against an opponent who outweighed him by 40 pounds. Figuring it was the start of a promising career, Donahue’s handlers wanted him to fight another young heavyweight named Jerry Quarry, who would go on to become “The Bellflower Bomber.”

But Donahue’s new pursuit was put to a quick end by his father, Dr. Bill Donahue, who was concerned for his welfare.

“If you want to live in my house and eat my food,” the elder Donahue said, “you will not box.”

The NCAA Board of Directors agrees to allow athletes to start earning money based on their fame and celebrity without fear of endangering eligibility.

Donahue attended L.A. Valley College for a year before arriving at UCLA as a 197-pound walk-on who didn’t play one snap all season.

Tommy Prothro, then UCLA’s coach, didn’t even know Donahue’s name, calling him Donny Donovan. Donahue was similarly crushed when Prothro acknowledged that he didn’t mind losing him to an ejection from a game along with the Stanford quarterback. “I’ll trade a defensive tackle for a quarterback anytime,” Prothro quipped.

But Donahue would gain more than respect over his final two seasons as one of Prothro’s gutty little Bruins. He became first-string defensive tackle while starting 21 consecutive games, including the Bruins’ epic upset of top-ranked Michigan State in the 1966 Rose Bowl.

His coaching career had a similarly fortuitous rise.

Donahue’s first job was in 1967 as an unpaid assistant under Rodgers at Kansas, where Donahue received only a movie pass to every theater in town as well as an invitation to eat with the football players. He made ends meet by managing an apartment complex.

The next season, Rodgers put his young assistant on staff, paying him $7,500 per year. Donahue followed Rodgers to UCLA as an offensive line coach when Rodgers got the head job before the 1971 season and stayed under Dick Vermeil when Rodgers departed for Georgia Tech three years later.

Donahue was about to get his big chance. Vermeil resigned after the 1975 season to become coach of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles at a time when the Bruins were on the eve of the period when high school seniors had to declare their college allegiance. Fearing an exodus of recruits should he hire an outsider, UCLA athletic director J.D. Morgan tabbed Donahue as Vermeil’s successor.

“I promised J.D. I would stay and build the program,” Donahue said on the day he announced his retirement in 1995. “I feel I’ve met my commitment.”

Donahue flirted with three NFL coaching jobs, only to stay at UCLA. He seriously considered offers from the Atlanta Falcons and Dallas Cowboys and also contemplated taking over the Los Angeles Rams job in 1994 before learning the team was headed for St. Louis.

He finally did make it to the NFL in 1999, serving as director of player personnel and later general manager of the San Francisco 49ers. Donahue held the latter post for four seasons before returning to the broadcast booth.

He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a coach in 2000. In his final years, Donahue remained a regular inside the Rose Bowl press box that was renamed the Terry Donahue Pavilion in his honor before the 2013 season.

“I’d hate to leave this place,” Donahue once said of UCLA, “even for heaven.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.