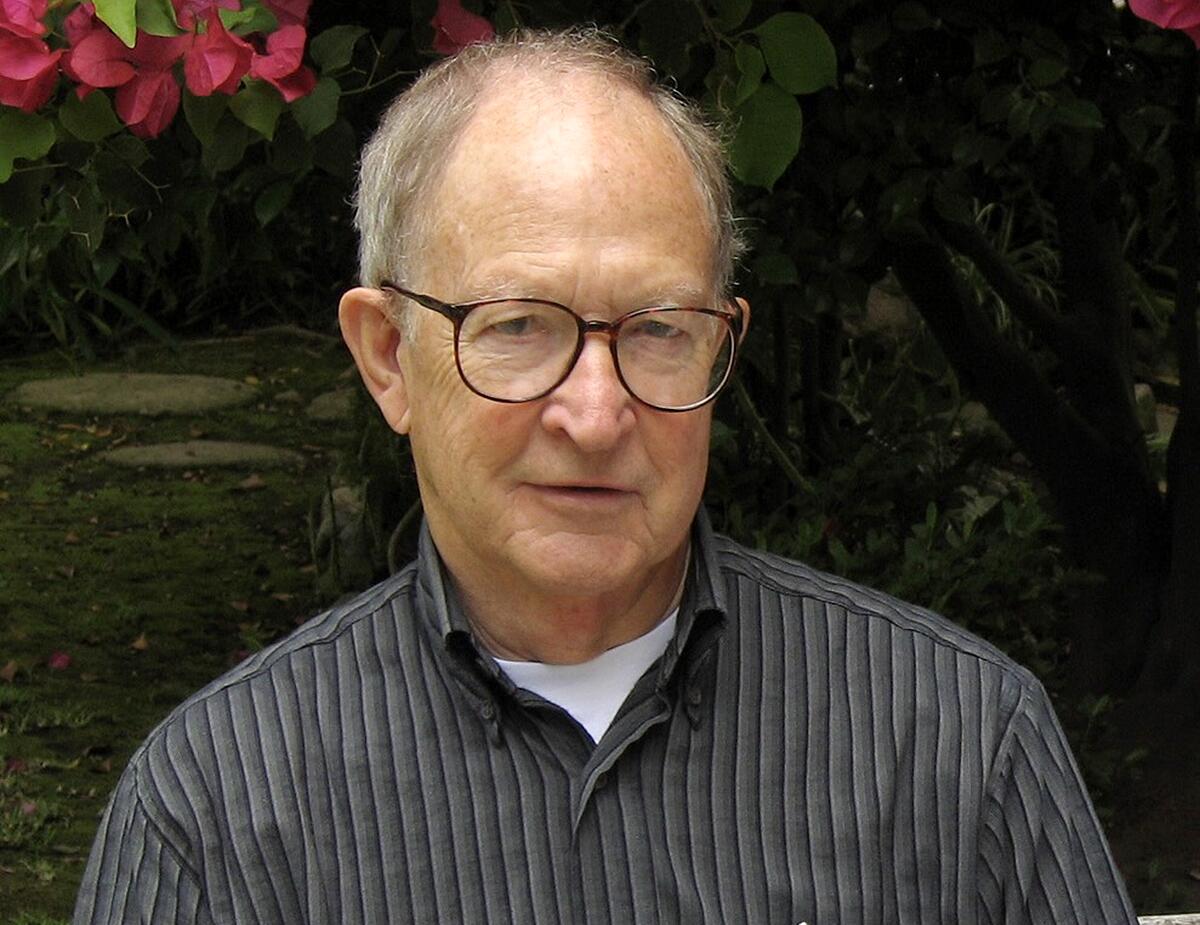

Harry Kelsey, former chief curator at L.A.’s Natural History Museum, dies at 93

- Share via

In the Archives of the Indies in Seville, Spain, Harry Kelsey pored over stacks of historical documents detailing the Spanish conquests in the New World. He nearly froze in the 16th century building as he taught himself how to decipher ancient writing systems and read Spanish.

“I was seated at a table wearing a scarf, overcoat and gloves with the fingers cut off so I could take notes,” Kelsey told the Los Angeles Times in 1985.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County planned to exhibit a chunk of California history, spanning from 1540 to 1940, and as chief curator of history, Kelsey volunteered to nail down how explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo built his sturdy ship. That way the museum could commission a replica of the vessel.

The more he researched, the more Kelsey grew fascinated with the explorer credited with providing the oldest written record of mankind in the West Coast. And he stumbled upon documents pinpointing Cabrillo’s birthplace — a point long debated by historians.

“Many historians have said he was Portuguese,” Kelsey said. “Perhaps successive writers have accepted as fact statements made in early chronicles. I discovered he was born in Spain, probably around 1498 or 1500.”

Years later, King Juan Carlos of Spain recognized the historian for the feat, a testament to decades of dogged work Kelsey pursued to learn more about the world and share its intricacies. He published numerous books on historical figures such as English explorer Francis Drake and the early, unsung Spanish mariners who traveled the globe. He also played a key role in helping establish downtown Los Angeles’ Broadway Theater and Commercial Historic District.

“He was a great one for delving into the history,” said Christopher Addé, manager of general collections at the Huntington Library in San Marino. “He knew his stuff and made sure a fact was a fact. He challenged general concepts about various people because of the research he’s done, and that’s what a good researcher does.”

Kelsey died Jan. 28 at his Altadena home surrounded by family. His son, Edward Kelsey, said his father suffered from congestive heart failure, prostate cancer and lung disease. He was 93.

Kelsey’s fascination with learning likely stemmed from his parents, who were teachers. Kelsey, who was originally from Illinois, served in the U.S. Army and later pursued his interest in history by using his G.I. Bill to return to school, earning his master’s and PhD in history in 1965 from the University of Denver.

Kelsey started at an insurance company to earn money as a newlywed until he landed a role as state historian for Colorado. The history buff held similar titles throughout the U.S. until a grant allowed him to study out of California’s Huntington Library. There, Edward Kelsey said his father knew he preferred Southern California’s impeccable weather to Michigan’s harsh winters and told his wife and eight children about their upcoming move.

At the San Marino library, Kelsey enjoyed leafing through its vast collection of Western and European history.

“To be able to wander among the stacks and pick out what information you needed, it helped him a lot,” Edward Kelsey said. “He said there was a lot of old, old documents — four or five or 600 years old — that he could only get what he needed by seeing them in person.”

Kelsey later began his role at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. His work on Cabrillo’s ship led him to eventually publish a biography on the explorer. He dedicated eight years of research, traveling to Spain often to review primary documents.

Colleagues commended Kelsey’s ability to handle original documents and manuscripts. They said the historian excelled in translating 16th century Dutch and the logbooks of early European explorers.

“Harry made sure that someone was quoting a fact, he wasn’t going to quote it verbatim,” Addé said. “He wanted to look at it from the beginning, with his own eyes, and own interpretation. He liked to get to the bottom of research.”

Before Pope John Paul II canonized Father Junipero Serra, debate broke out in the Catholic community. Supporters argued it was only a matter time for Serra’s sainthood, while others objected over his mistreatment of California natives. Today Serra, who founded nine of California’s missions, remains a controversial figure.

Kelsey, a devout Catholic, also weighed in.

“Father Serra was certainly a very human man,” he told The Times in 1986. “He had lots of weaknesses, I suppose, but he had tremendous dedication and strength of purpose. . . . He was a man who devoted himself to the Indians and really tried to help them.”

Kelsey said that life was hard for California natives when Serra arrived, adding that the idea that they “lived in a sort of pastoral Eden, in perfect peace with one another, is just the greatest malarkey. There’s absolutely no truth to it at all.”

Giles Mead, the late director of the history museum, grew fond of Kelsey’s approach and ensured the historian would have a place to continue his work. The Mead Foundation endowed an office at the Huntington Library and — for 50 years — awarded Kelsey grants to cover his research expenses. For years, Kelsey could be found in his office until the pandemic interrupted his routine.

Mead’s daughter, Parry Mead, said her father was in awe of Kelsey’s “meticulous attention to detail.”

“Dad used to say, ‘Harry is the only historian I know whose footnotes exceeded the narrative in his books!’ ” she said.

At a low point in Giles Mead’s life, Kelsey wrote almost daily letters to his friend. Using their mutual love of dogs, Kelsey spoke through his rescue pup, creating a unique voice to express his emotions to his friend. Parry Mead said she believes the letters helped keep her father alive.

Even after he retired, Kelsey continued pursuing his love of history. He traveled nearly annual — sometimes twice in a year — to walk historical routes such as Spain’s Camino de Santiago, where winding paths stretched from the coast to countryside hills. And just like the European navigators he studied, Kelsey wrote letters to his loved ones about his adventures.

“One time he literally did have a Saint Bernard find him because he got stuck in snow,” Addé said. “He made kind of light of it, but he did say at the time it was really tough going.”

In his spare time, Kelsey enjoyed refurbishing antique cars in his garage. He restored a 1915 Dodge he once drove in a Disneyland parade and built a replica of a 1920 Model T Ford. Even in his final days, his children helped him work on his 1960s Chevy pickup.

“He was the sort of person you never thought would die ever because at 92ish, he was still talking about going on pilgrimage trips,” Addé said. “And I’m thinking, ‘Well, I just want to get to 92.’ ”

Kelsey was most recently working on a new book, translating the account of a person who was on the ship with the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan when he was circumnavigating the world.

Kelsey is survived by seven children, 17 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his wife and a son.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.