Government: When push comes to nudge

- Share via

News came last month that the Obama administration, following the lead of British Prime Minister David Cameron and his government’s so-called Nudge Unit, is recruiting behavioral scientists to help shape regulatory policy. Nudges are ways of offering choices that make people more likely to choose a particular option but preserve their ability to make a different choice.

This usage of “nudge” was coined in 2008 by economist Richard Thaler and legal scholar Cass Sunstein, but the concept was first studied more than a decade ago by economist Brigitte Madrian and insurance executive Dennis Shea. They noted that when employees joined a company with a retirement savings plan like a 401(k), they typically had to affirmatively choose to enroll. Then they had to select investment options and specify an amount to save from each paycheck.

Setting aside income tax-free for retirement is good for most employees. But for various reasons, including inertia, many failed to enroll. Madrian and Shea evaluated the effect of a simple solution: switch the default choice so that employees must check a box to opt out of the savings plan rather than opt in. Then, if the employees did nothing, a default percentage of their salary would go to a default investment. After the change, the number of savers jumped.

Several features of this archetypal nudge should make it attractive to people of all political stripes. Employees have exactly the same choices before and after the nudge; nudges by definition neither forbid nor mandate any choice. And the nudge makes it more likely that nudgees will, in reflective moments, feel they made the best choice they themselves prefer.

In the wake of the Obama administration’s announcement, some have called governmental nudges manipulative, even creepy. But there is no evidence that nudges alter individual preferences. What is true is that some nudges work without our being aware of them. If you don’t read your employment documents, then after the 401(k) nudge, you will save for retirement, whereas you would not have before. But people whose behavior flips when the default option changes are likely deciding on autopilot anyway.

Are such unexamined “choices” worth preserving in light of the considerable benefits that nudges can yield for both individuals and society, often by encouraging personal responsibility and forward-looking behavior? In Britain, simply telling taxpayers that most of their peers paid up on time increased timely filing by 15% over a three-month period. And asking people who lost their jobs to devise concrete plans for finding new ones led to a 15% to 20% decrease in their likelihood of claiming unemployment benefits 13 weeks later. Those are win-wins.

Nudges enjoy an additional, overlooked advantage over other forms of regulation: Before they are enacted, they can be evaluated with randomized, controlled trials to ensure that they are effective. This would be impractical and arguably unethical with tax incentives and outright bans.

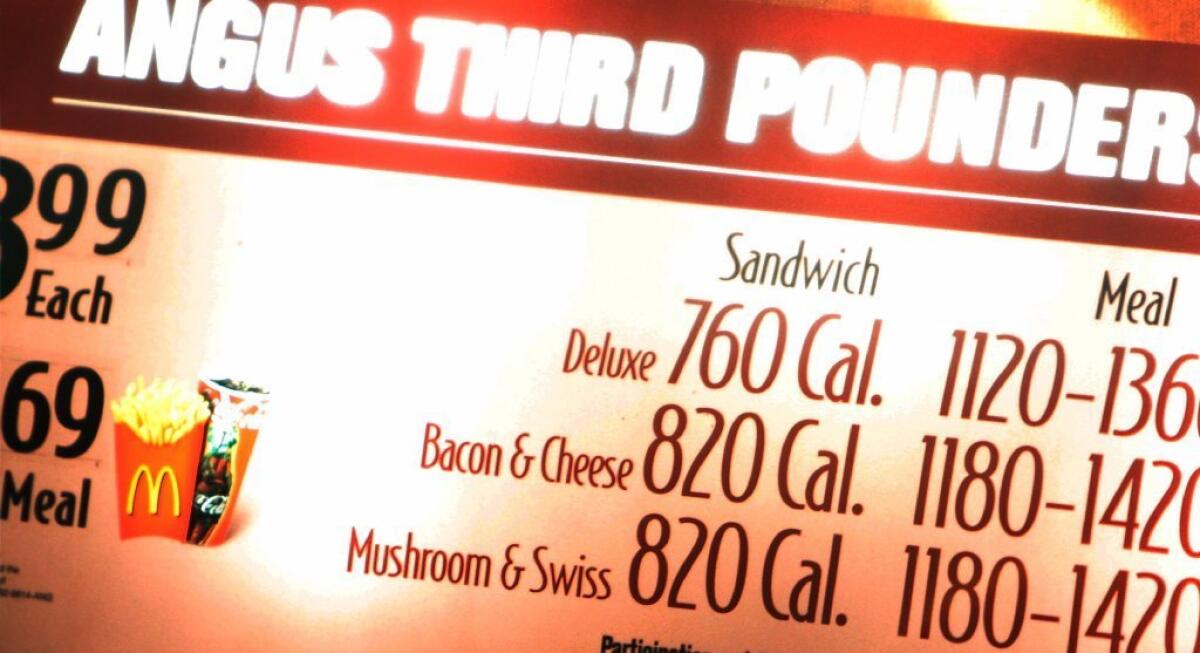

Of course, just because nudges can be tested does not ensure that they will be. Obamacare requires chain restaurants to post calorie counts for standard menu items, a policy similar to one enacted by New York City in 2008. It seems intuitive that this should nudge consumers to make better choices, thereby reducing obesity and saving potentially billions of dollars in healthcare spending.

But that intuition was not tested experimentally in advance, and observational studies of calorie displays are inconclusive. One study found that they had no effect, but another found a 6% decrease in calories purchased. The federal rule added a requirement that chain restaurants also post a suggested total daily caloric intake, perhaps on the assumption that telling consumers that a Big Mac has 550 calories will mean more when framed by the advice that an adult should eat about 2,000 calories a day. But a recent study undermined this intuition too: Benchmarks did not reduce purchased calories, and may have ironically promoted consumption of higher-calorie items.

Implementing untested nudges has real costs. According to the federal government, the Obamacare calorie rule imposes a new 14.5-million-hour paperwork burden, and first-year compliance costs for businesses could total $537 million. If the benefits of a government intervention are not expected to outweigh its costs, then doing nothing will often be the better policy choice.

Even if testing shows a nudge to be effective, it will rarely if ever benefit everyone who is subject to it. (In some cases, such as making posthumous organ donation the default, nudges do not directly benefit any nudgee, although there may be other reasons to support such proposals.) Although the Obama administration claims that its nudges will “help people to achieve their goals,” no government can know and simultaneously promote the many goals of a diverse citizenry. Nor do all people make irrational choices in the absence of nudges; some targets of a nudge will already have made choices that reflect their considered preferences.

But all this is true of every act of lawmaking. Under the Supreme Court’s expansive commerce clause jurisprudence, the regulators who would nudge us already can, in most cases, shove us instead. And shoves, unlike nudges, prevent people from making choices that differ from the government’s.

When some choice has to be the default — everyone must either save for retirement or not — nudges sensibly make it easier for people to choose what most of them prefer (or what is expected to yield the greatest social benefits), while allowing the minority to make a different choice with minimal effort.

Those who fear that nudging will put us on a slippery slope to an Orwellian nanny state ought to recognize that we are already on that slope. Nudges offer an offramp to a more sure-footed terrain that people across the political spectrum should prefer.

Michelle N. Meyer is a professor of bioethics, law, and policy at Union Graduate College. Christopher Chabris is a psychology professor at Union College and the coauthor of “The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.