Editorial: Want to help protect women worldwide? Apparently, Congress doesn’t.

- Share via

Recently, two girls, aged 14 and 15, were gang-raped in the poverty-stricken Uttar Pradesh state of India. They were later found dead, hanging from the branches of a mango tree. In Pakistan late last month, family members of a pregnant woman beat her to death with bricks and clubs outside a Lahore courthouse for marrying a man of her choice instead of the cousin her family preferred. Last February, in conflict-ravaged South Sudan, 20 women in the Mayendit region were raped by soldiers. Then the soldiers urinated into victims’ mouths, according to an eyewitness.

The litany of abuses perpetrated against women and girls around the world goes on and on. The U.N. Development Fund for Women estimates that 1 out of every 3 women will be beaten, coerced into sex or otherwise abused by an intimate partner during her lifetime. The fund also reports that between 100 million and 140 million girls and women have gone through female genital mutilation. More than 60 million girls worldwide are child brides, married before the age of 18. And women in war-ravaged countries are especially vulnerable; in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, there have been at least 200,000 cases of sexual violence since 1996, mostly involving women and girls, according to the fund.

Many of the most horrible of these atrocities take place in countries that receive tens of millions of dollars in annual economic and development aid from the United States. It makes sense for the U.S. to leverage its economic influence to persuade countries in which abuse based on gender is part of the culture to take steps toward preventing it. The International Violence Against Women Act — HR 3571 in the House and S 2307 in the Senate — calls for the U.S., in countries where it is engaged in foreign assistance, to address the problem of violence against women and girls, to help create programs to educate local populations about recognizing and preventing such violence, to promote gender equality and to support existing programs that are confronting these issues. The proposed law would also make the U.S. State Department’s Office of Global Women’s Issues permanent, headed by an ambassador at large appointed by the president and reporting to the secretary. If passed, it would also require that U.S. contractors and grantees take measures to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse within their workforces.

The legislation, introduced by Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) and Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), is broad and somewhat vague. But it should not be controversial. It does not call for cutting aid to countries, even if they have a vile history of tolerating the abuse of women. Nor does it discourage or divert funds from programs that might be used to stem violence against men and boys. The legislation concentrates on women and girls because they are disproportionately the victims of rape, often carried out with impunity; in some places they can be sold or given away to men, or killed for disobedience.

There’s no denying that the United States has its own continuing domestic problems with sexual violence, human trafficking and gender violence. This proposed law is not meant to suggest otherwise. But that does not mean that this country should not also have a role in fighting the violence against women that has become routine in other parts of the world, even as it seeks to address such issues here at home.

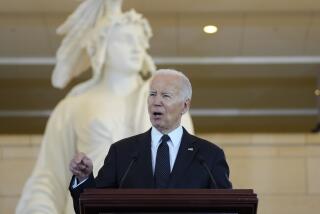

It’s difficult to understand why anyone would oppose a plan to combat gender-based violence, yet the International Violence Against Women Act has languished in both houses of Congress. Oh, wait — could that be because it is supported by the Obama administration, and in an earlier incarnation in 2007 it was cosponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden?

Particularly offensive are the attempts of some opponents to pretend that the proposed law is merely a misguided liberal hobby horse. One critic, for instance — a research fellow at the Independent Institute, a nonpartisan think tank — called it an attempt “to insert politically correct feminism into the structure of other nations.” Not only does that malign feminism and reduce rape and gender violence to issues of political correctness, but it misses the point of the legislation. This isn’t about ideology, it’s about human rights.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.