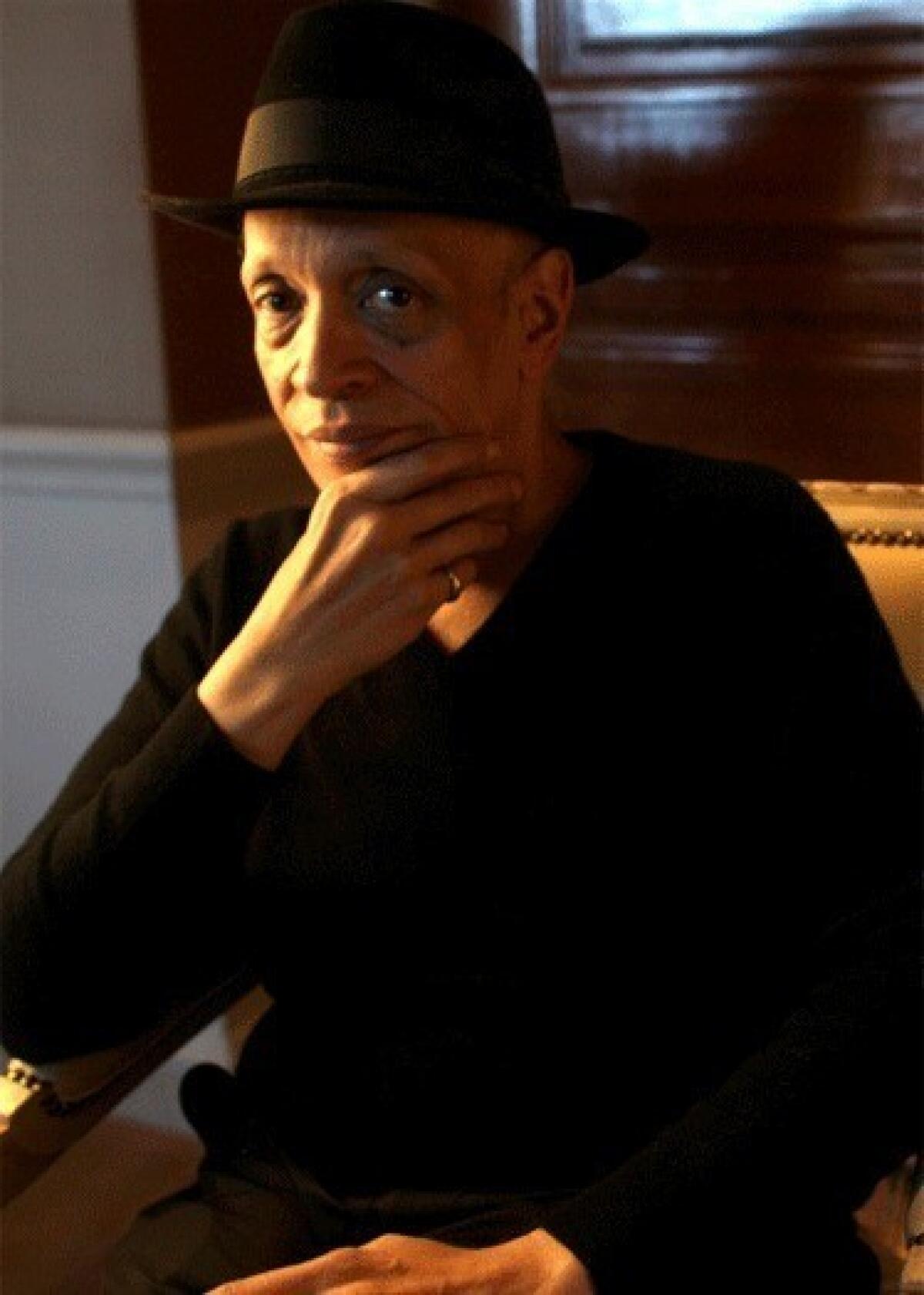

Walter Mosley, L.A.’s easy writer

- Share via

You can take Walter Mosley out of Los Angeles — in fact, Mosley did so himself, moving to New York decades ago — but you can’t take L.A. out of Walter Mosley. The master of several genres keeps the city present, from his Easy Rawlins detective novels set in black postwar Los Angeles to the Greek-myths-in-South-Central elements in one of the two novellas in his latest volume. Mosley appeared to wrap it up with Rawlins in “Blonde Faith” in 2007, but five years later, he’s found more for his most famous detective to do, just as Mosley has for himself. He has a fledgling production company, B.O.B. (for “Best of Brooklyn”) Filmhouse, and still writes with one foot in 212 and another here in 213.

One of the characters in your new novella “The Gift of Fire” is Prometheus. Did you read mythology when you were a kid?

I was always aware of mythology. I read comics, which are also very influenced by mythology.

Prometheus is an example of no good deed going unpunished, in Greek myth and in your book.

And then they punish him again. That’s the way it is. There’s a political element to all six of the novellas I wrote, not that I was aware of it when I was writing. When people ask what the books are about, I say they’re science-fiction in which a black protagonist destroys the world one way or another.

There’s an incipient and subversive power in that.

Recently, someone was saying, how can we change the world? And I said, it’s easy, all we have to is trust each other. It’s a giant notion. And that’s really what “The Gift of Fire” is about — mutual trust.

So many things get thrown into the sci-fi category. Ray Bradbury said he didn’t like that label.

Understandable. He was telling parables and speculating about the nature of humanity. I’m trying to do the same thing. I don’t mind calling it science fiction or speculative fiction. The problem today is that everybody has forgotten that some of the most important literature of the 19th and early 20th century was science fiction. Jules Verne invented the 20th century. “1984” by Orwell. H.G. Wells took us beyond the imagination before the [world] wars and into this whole new world that we were facing. These were incredible books and writers who were major world thinkers. And for some reason contemporary literature has forgotten that and made almost all science-fiction writers outcasts, which is too bad because they are certainly the smartest writers and in many ways the most important writers.

One element in another of the novellas, “On the Head of a Pin,” is a creation called “the Sail,” described as a fiber-optic tapestry that becomes a portal to time. We just had the late Tupac Shakur “appearing” virtually at the Coachella festival. Isn’t that what you were getting at?

That’s true — you kind of re-create the world. That’s the first level of the Sail. The other level is that the world doesn’t need re-creating because it’s happening again and again and again.

What is your production company up to?

I’m looking to make television and shows and movies — my kind. I’m very happy with the movies that have been done [of his work]. I’m not happy with the regularity; I’d like to do more. I wrote a script based on “The Long Fall” for HBO, and I’m waiting for them to respond. I did a script about Easy Rawlins which I gave to NBC and they passed on that. Sam Jackson’s company has an expressed an interest in doing “The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey” as a movie.

You worked as a computer programmer before most people knew what that was. Is your writing more tech savvy because of it? More orderly? Do you tweet?

No, no and no. I look at what computers can do. The iPod: 15 years ago I had this thing called the Personal Jukebox, the same kind of machine, way before the iPod. I would be the only person in the airport working on a laptop computer, but now it doesn’t actually interest me anymore.

We can mistake mere change for progress?

There’s technological progress in ways that might be cultural progress, but you mustn’t mistake that for human progress. There’s a difference. There’s no novelist today any better than Homer. It’s just that we don’t have to go from town to town telling our stories from memory.

I’m not blaming computers or anything like that. Beginning to understand advancement would be an advancement of the human race, and we haven’t been able to do that. I’m worried if [humans] are happy or not happy, and if they have the potential for happiness. The word “happiness” is in that document [the Declaration of Independence], but there’s no Department of Happiness; there’s no commitment to happiness. We have the right to pursue it; we have no attempt to define it.

Some brick-and-mortar bookstores have gone under and others are struggling. Is this just an inevitable iteration of technology?

Absolutely, and it’s inevitable as long as we don’t face what we’re doing and make decisions about how we’re living. We have a country run by corporations, not by people, but we think we live in a democracy. You say, “Yeah, I vote, but for four years I just wait and then come back and say, ‘I’m dissatisfied.’” We should be working together: Where were you the last four years? So long as we don’t take the initiative and act upon our best interest, we’ll have the world that we live in.

You declared that the 10th Easy Rawlins novel would be the last. Did you feel like Arthur Conan Doyle, when he evidently sends Sherlock Holmes over Reichenbach Falls to his death?

I did a little bit — especially since I just finished writing a new Easy Rawlins novel.

Did you know all along you were going to bring him back?

I wasn’t absolutely sure, no. I knew I needed to stop writing him for a while, and that might have been forever, but it turned out that it wasn’t. It dawned on me in kind of a transitional period: Hey, I’ll write a new Easy Rawlins novel. It’s called “Little Green,” and I really enjoyed writing it.

You left L.A. in your early 20s. When you’re here now, what do you find changed?

When I was in L.A. as a kid, L.A. had no cuisine. I remember asking a guy in a fish restaurant about different fish, if his fish was frozen, and he said, “Man, this is L.A. — all the fish is frozen! Fresh fish? You’ve got to go to Louisiana if you want fresh fish.” Now, of course, it’s completely different.

What are the big cultural differences between here and New York?

Is there any cultural difference in America anymore? There are surface differences, really. The ideas people live by are similar all over the nation. There are minor differences. If you’re a black man, for instance, there’s no place in the country that’s safe for you. The prisons are the same, the education systems are the same. To one degree or another it might be somewhat different, but not enough to say it’s a different culture.

What’s the difference between the Los Angeles in “The Gift of Fire” and in the detective novels set in postwar L.A.?

“The Gift of Fire” is more California, between the Bay Area and L.A. In the [other] novels, the city is very much more a character.

All the black people who came to L.A. after World War II had reduced expectations, [but] they were very optimistic about those expectations. They thought, “I could be a janitor, a cook and a house painter all at the same time and buy me a house.” Those reduced expectations no longer belong to people in the culture. You have black sports figures and professors and writers and movie stars. You have a black president. Some people are more optimistic, [but] for some people downtrodden by the political and economic system, that’s just not true.

What do you read for your own pleasure?

I love science fiction, and I read history. I think I will always be reading Will and Ariel Durant’s “The Story of Civilization.” Hundreds of years ago, [French author] Cyrano de Bergerac wrote a sci-fi novel about going to the moon. I still can’t figure out whether the guy was joking, but the way he talked about going to the moon was so funny — and he wrote it in 1640 or something!

You’re reading a nearly 400-year-old novel?

Yeah, it’s very cool.

This interview was edited and excerpted from a taped transcript. An archive of Morrison’s interviews can be found at latimes.com/pattasks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.