Opinion: What L.A. can learn from the 1992 Barcelona Olympics

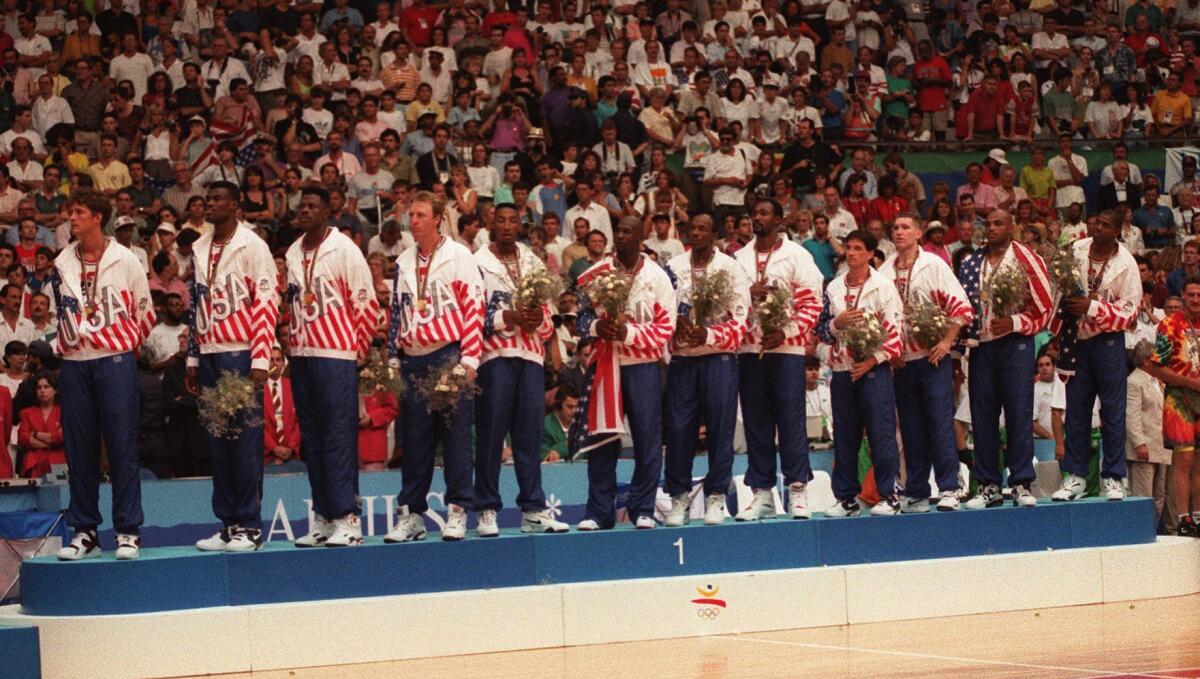

Members of the USA basketball “Dream Team” pose with their gold medals after defeating Croatia, 117–85 to claim the olympic medal in Barcelona, Spain on Aug. 8, 1992.

- Share via

The surprise has worn off Los Angeles’ last-minute sprint from distant runner-up to official U.S. host city nominee for the 2024 Summer Olympics. Now, shock has given way to both elation and unease as Angelenos consider the actual realities of the prize they are competing for. Fears of saddling the city with crippling financial debt may be well-founded. But before anyone panics, it’s worth examining the success and horror stories of cities that have hosted the Olympics in the past, and asking what L.A. can learn from them.

The most relevant example for L.A. 2024 is, of course, L.A. The 1984 Olympics are remembered as the most commercially successful Olympics since 1932 -- coincidentally, the first time L.A. hosted the Games. But net economic gains, unevenly distributed and often disputed in any case, are only one measure of success. Just as important is the impact on urban infrastructure. In that particular contest, Barcelona’s turn hosting the 1992 Olympics is often regarded as the gold medalist.

Prior to the 1992 Olympics, Barcelona was known as the regional capital that Spain’s long-reigning dictator Francisco Franco had purposely forgotten -- as retribution for opposition to his rule. When Barcelona was awarded the Games in 1986, more than a decade after Franco’s death, the city still had a dysfunctional airport, maddening congestion, and an inaccessible waterfront blighted by industry. Then it won its Olympics bid. Channeling an extraordinarily high percentage of its Olympic budget -- nearly 85% -- toward infrastructure improvements, Barcelona converted its waterfront into a center of nightlife and tourism and became the rare major European city to offer an enjoyable sand and surf experience. It also constructed a ring road, and brought its airport up to international standards, eventually becoming the fifth-most visited city in Europe and halving its unemployment rate in the process.

So is Barcelona 1992 a role model for L.A. 2024?

In many ways, no. Barcelona’s pre-Olympics infrastructure improvements, including a 35% increase in hotel capacity, sparked a lasting boom in overseas visitors. By contrast, L.A. is already an established international tourist destination, and its hotels can comfortably accommodate the record 45 million total visitors expected this year. Unlike post-Franco Barcelona, L.A. is already heavily invested in light-rail expansion, and five of Los Angeles International Airport’s passenger terminals are already undergoing a multibillion-dollar reconstruction. L.A. already has a ring road, so to speak, in its freeway system.

Then, of course, there’s the sprawl factor. Whereas Barcelona’s revitalized waterfront lies only a quick stroll from its concentrated urban core, L.A.’s population and tourist infrastructure is too widely dispersed to enjoy the same benefits Barcelona did in 1992 from localized improvements. While several individual neighborhoods could benefit from the Olympics, it is L.A.’s overall livability, not its tourist industry, that most needs a boost. The closest 2024 equivalent to Barcelona’s waterfront revitalization might be the plan to build an Olympic Village along the L.A. River at the L.A. Transportation Center (otherwise known as the Piggyback Yards). The Village will then be converted into residential housing after the Games. While this could yield some much needed affordable housing (how much remains unknown) and better transportation connections, planners are promising “further neighborhood renewal,” not dramatic change a la 1992.

Barcelona did make one improvement, however, that, if emulated in Los Angeles, would be noticed by both residents and visitors: the airport experience. After the city constructed a practically new airport at El Prat, the number of air passengers doubled. Already the fifth-busiest airport in the world, LAX doesn’t need more passengers so much as better connections to local transportation. County transportation officials have already appropriately applied to fast-track construction of a “people mover” linking LAX to the future Metro Crenshaw/LAX rail line.

Instead of simply widening the LAX gateway though, it might make sense to give Eastsiders -- and Olympics visitors -- access to what so many other comparably-sized metro regions have: a second major airport. One possible candidate is Burbank’s Bob Hope Airport, where an expansion is already planned. Conceived before the 2024 bid, however, the expansion is modest, increasing the size of the terminal without adding any gates to the existing 14. (By comparison, Chicago and New York City’s second-busiest airports, Midway and LaGuardia, have 43 and 72 gates respectively.)

Could the 2024 Games affect these plans? In the past, Burbank leaders have seen little to be gained in exchange for the greater noise and traffic. Were the expansion scaled up sufficiently to accommodate Olympics visitors, however, the benefits in investment and recognition might outweigh the drawbacks. If Burbank officials don’t like the idea of “Los Angeles” appearing in their airport’s new name, they might consider taking the bold steps needed to teach the world, as Barcelona did in 1992, what their city can offer.

Justin Clark is a journalist and scholar who writes about cities. Follow him on Twitter @Justin_T_Clark.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.