Op-Ed: Is the call for Zika virus abortions the new eugenics?

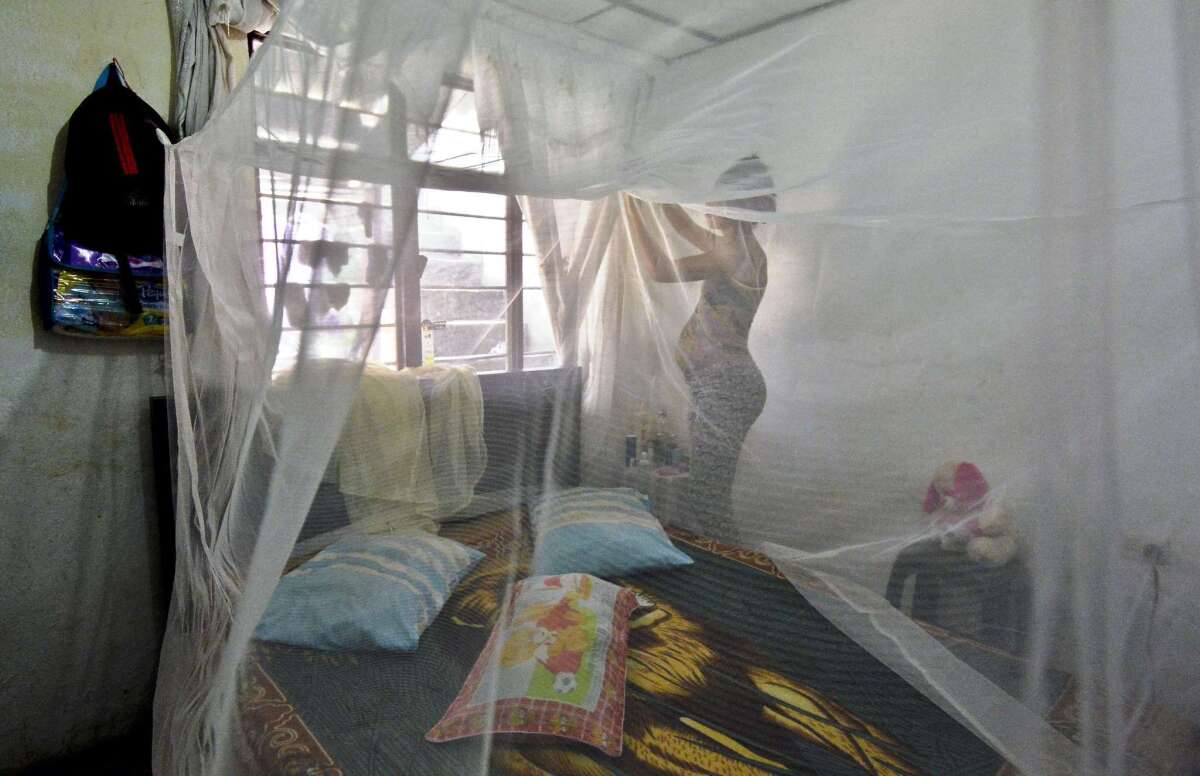

A woman who is seven months pregnant installs a mosquito net over her bed in Cali, Colombia on Feb. 17.

- Share via

When the World Health Organization declared the Zika virus a global emergency, it also claimed that the disease was tied to increased cases of microcephaly in babies. A day later, the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, which actively promotes the view that “access to abortion is a matter of human rights,” was putting pressure on countries in Central and South America to change laws that protect prenatal children from violence.

Other abortion rights activists seized on this new moment of opportunism. The blog ThinkProgress described it as “The Zika Virus’ Unlikely Silver Lining.” Slate’s feminist XXFactor blog sounded hopeful that Zika would be Latin America’s “rubella moment” — recalling that, in the 1950s, rubella’s association with birth defects began to make otherwise illegal abortion palatable in America. Amnesty International talked of the “devastating consequences” of antiabortion laws. Planned Parenthood’s international arm exploited the news to develop a special Zika virus fundraising campaign.

Abortion is a crude response to the possibility of microcephaly.

This is a remarkable response, not least because the link between Zika and microcephaly has not yet been established. The WHO’s website cautioned that “no scientific evidence to date confirms a link between Zika virus and microcephaly.” Colombian officials reported 3,177 pregnant women infected with Zika with no evidence that the virus has caused even a single case of microcephaly. Two physicians organizations, in Argentina and Brazil, suggest that a pesticide could be the cause instead, noting that Zika has a long history in Latin America without an association with birth defects.

Even if a connection is established, abortion is a crude response to the possibility of microcephaly. The prenatal test for the disease — ultrasound — may not find evidence of it until the third trimester. That’s well after the baby can feel pain and live outside the womb, and past the point when a majority of those who identify as pro-choice are willing to accept abortions. (All prenatal tests, but especially those early in pregnancy, have a significant failure rate.) Furthermore, the prognosis for a child with microcephaly can vary widely — as a Brazilian journalist who has microcephaly pointedly reminded the world in a report from the BBC.

It isn’t difficult to understand why Latin Americans might be resentful of groups such as he U.N., Amnesty International and the International Planned Parenthood Federation and their long-standing attempts to impose foreign moral and legal principles onto those who think differently. In the U.S., only a few antiabortion groups have raised objections to what could easily be seen as yet another example of neocolonialism, or worse, as a new eugenics. Why so little reaction?

It may be that the eugenic impulse is so deeply embedded in U.S. culture that we don’t even recognize it. As early as 1909, Indiana passed eugenic compulsory sterilization, a law infamously upheld by the Supreme Court in an opinion that concluded by saying “three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Nor was this an unpopular position. A Fortune magazine poll in 1937 found that 2 in 3 Americans supported forced sterilization of “mental defectives.” Margaret Sanger, founder of an organization in 1921 that would become Planned Parenthood, insisted that the imbalance between “the birthrate of the unfit and fit” was “the greatest present menace to civilization.”

This sort of thinking is still expressed in the United States, though in a different form. According to Arthur Caplan, founding head of the bioethics program at New York University, “more than 85% of parents who learn through prenatal testing that a fetus has Down syndrome terminate the pregnancy.” This despite studies that find children with Down are actually happier than those who are “normal” and that families with such children are also disproportionately happy. These facts, however, are not always shared with patients when physicians describe the possibility of having a child with Down syndrome.

Medical ethicists have long worried about the language used by physicians when they speak to parents about genetic testing and abortion. Disability advocates argue that “directive” and “ableist” language has played a significant role in the 85% abortion rate. Many of us have heard tearful or even rage-filled accounts from parents who were strongly advised not to simply have prenatal tests but also to abort if the tests came back positive. In response, disability rights groups have led the way in passing laws requiring the medical community to end these unethical practices and to give their patients the actual data on positive outcomes.

Perhaps this is the beginning of a much-needed organized resistance to our impulse toward eugenics. But as the shameful reaction to the Zika outbreak demonstrates, we still have a long way to go. The practice of discarding the vulnerable when they become inconvenient is precisely what Pope Francis has criticized about our contemporary “throwaway culture.” Francis insists we give priority to the most vulnerable among us, not the most productive. Indeed, if someone is seen by others as a burden this is the first sign that we should give them special attention and care.

The rush to advocate for abortion as a response to the Zika virus is grounded in ignorance and expedience. If these organizations were actually interested in helping people with Zika — rather than exploiting the outbreak for a broader agenda — they would have held their fire until we know more. They also would have done more to wrestle with the views of the disability-rights community.

Instead of arrogantly insisting that developing nations must change their laws to suit someone else’s ideology, abortion proponents and the media would be better served by taking a critical look at the dark tendency here and elsewhere to turn to eugenics as a solution to a problem like Zika.

Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.