Op-Ed: The town that white supremacist Richard Spencer calls home

- Share via

Whitefish, Mont., is a bucolic town that breeds travel cliches. It’s nestled in the mountains and around a lake. It’s full of skiers and kayakers, climbers and snowmobilers, depending on the season. A tourist town, a ski town, a town of picture-perfect views around every corner and Glacier National Park is just a half-hour’s drive away. Until recently, it was a quiet town too.

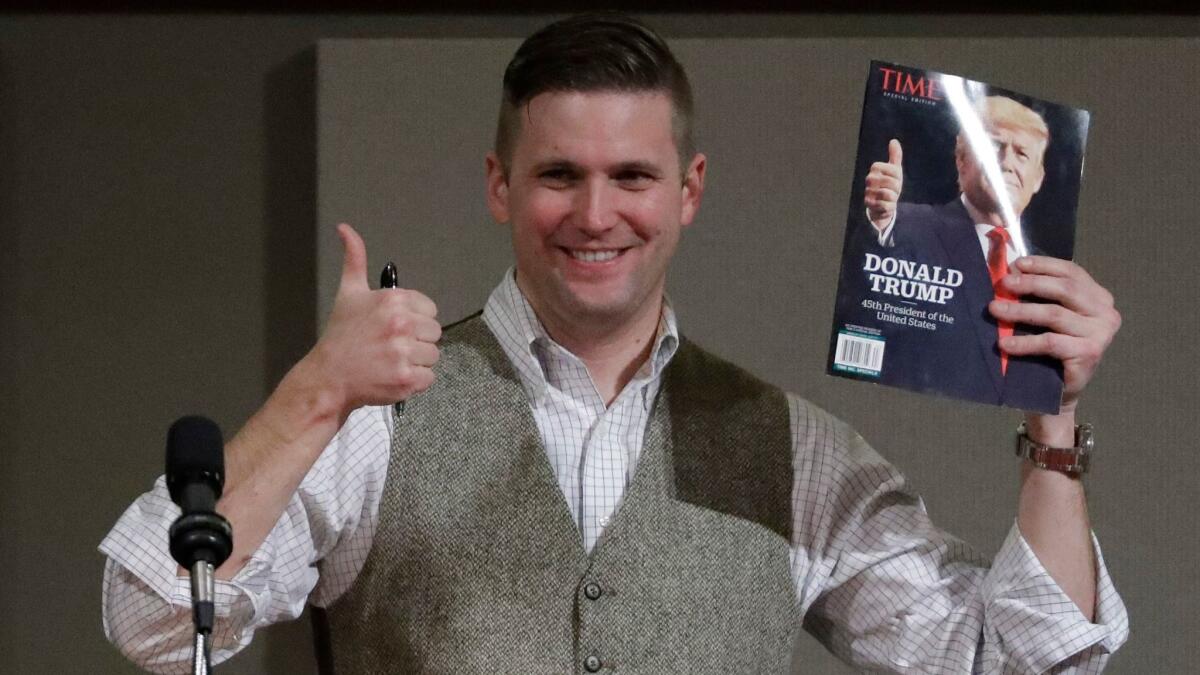

On a bright blue, snowy day earlier this month, a CNN film crew showed up in the main coffee shop. Nobody was under any illusions about why they’d come. Whitefish had been named in news articles all over the country — all over the world — as the town that the white supremacist Richard Spencer calls home. Already, publications from the BBC to the Montana Cowgirl political blog had asked locals if we supported the darkness in our midst, or simply speculated that we did.

Rumors and news fly fast in Whitefish, where the full-time population hovers around 6,000. The news, or rumor, was that CNN had expected to find a town where Spencer felt welcome, but the reading of an anti-discrimination statement at a packed City Council meeting a few days earlier had changed the story.

The world may have just gotten a whiff of Spencer’s well-groomed hatemongering, but Whitefish has been well aware of him [and his organization] for years.

The statement was actually a re-reading of one that passed in 2014. The world may have just gotten a whiff of Spencer’s well-groomed hatemongering, but Whitefish has been well aware of him and his innocuously named white supremacist think tank, the National Policy Institute, for years. While NPI’s mission statement uses bland positive language to declare its dedication to “the heritage, identity and future of people of European descent,” the truth of its aims can be found in Spencer’s more blunt declaration at a recent Texas A&M talk: “America,” he said, “belongs to white men.”

Again, none of Spencer’s views are news in Whitefish. Just because we’re aware of him, however, doesn’t mean there’s a whole lot we can do about him or his beliefs besides to publicly reject them. This is 2016, not 1620. We don’t have recourse to tar-and-feathering; we can’t confiscate Spencer’s property or banish him, nor would we want to.

Imagine you’re in a family with a crazy distant cousin. Lots of families have one of these. Let’s call him Cousin Dick. Everyone knows that Cousin Dick has a screw loose. He gets together with his conspiracy theory buddies and shoots the breeze. Whenever you and your family remember that he exists, you breathe a sigh of relief that his loose screws haven’t yet caused anyone real harm.

And then one day NPR and the Atlantic and Vice and the Washington Post show up and say, “So, Dick, tell us about your ideas for the world.” Everyone understands that Cousin Dick is nothing but a crazy distant cousin, but suddenly his warped worldview is being taken seriously. He’s been given a platform, and he’s making the whole family look bad.

Spencer seems to think he’s on a lifelong episode of “Mad Men”; women or anyone of color are just walk-ons — and they’re messing up the plot.

Whitefish, however, is very much rooted in reality. The recent City Council meeting where we re-read the anti-discrimination ordinance was indeed packed door to door. “The City of Whitefish,” the mayor read from the proclamation, “rejects racism and bigotry in all its forms and expressions.” Clapping and quiet cheers from the crowd, from the people I see every day at the schools and on the hiking trails. “The City of Whitefish repudiates the ideas and ideology of the white nationalist and so called alt-right as a direct affront to our community’s core values and principles.” More clapping, more cheers. And after private citizens and representatives from the Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau stood up to repudiate Spencer’s worldview, we got on to the rest of the town’s business, starting with 45 minutes on stormwater drainage solutions and dedicated parkland for a proposed new subdivision.

Does drainage seem irrelevant or quaint when the issue at hand is white supremacy? This may not be obvious to most readers, especially those from big cities, but our unity against racism and our dedication to nitty-gritty local problems are related.

Whitefish residents are — and have long been — deeply involved in the community. We show up for the kind of boring civic work that makes a town function: figuring out how to build a comprehensive cycling network that can be plowed in our snowy winters, dealing with grizzly bears and deer getting into people’s trash.

National media stories focus on the divides in our country, of the chasms between liberals and conservatives, rural people and urban. But every community, whether it’s vast Los Angeles or itty-bitty Whitefish, has the capacity to find common ground in the everyday nuts and bolts of making society function. And when we find commonality in those places, we begin to find it elsewhere, too.

We don’t agree about everything, like what exactly to do about that aging wastewater treatment plant, but we respect each other. Because we see each other as neighbors, not as “liberals” and “conservatives,” we quite naturally come together against hate — and rest secure in the knowledge that our community will survive the likes of Richard Spencer.

The National Policy Institute has a home here, but it’s not — as President Obama is fond of saying — “who we are.” What defines Whitefish is the decades we’ve spent working with landowners to build a trails system that connects wilderness to the town, the timber company’s offer to help the town buy and conserve lands that would permanently protect our drinking water sources, the way people here hold doors open for one another and all show up at the same coffee shop.

Spencer’s having his 15 minutes of fame. Whitefish will be here when they’re over.

Antonia Malchik is a writer based in northwest Montana. Her nonfiction book “A Walking Life” will be released in 2018.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.