Op-Ed: Donald Trump is a parody of American manhood — and that’s what lifts him

- Share via

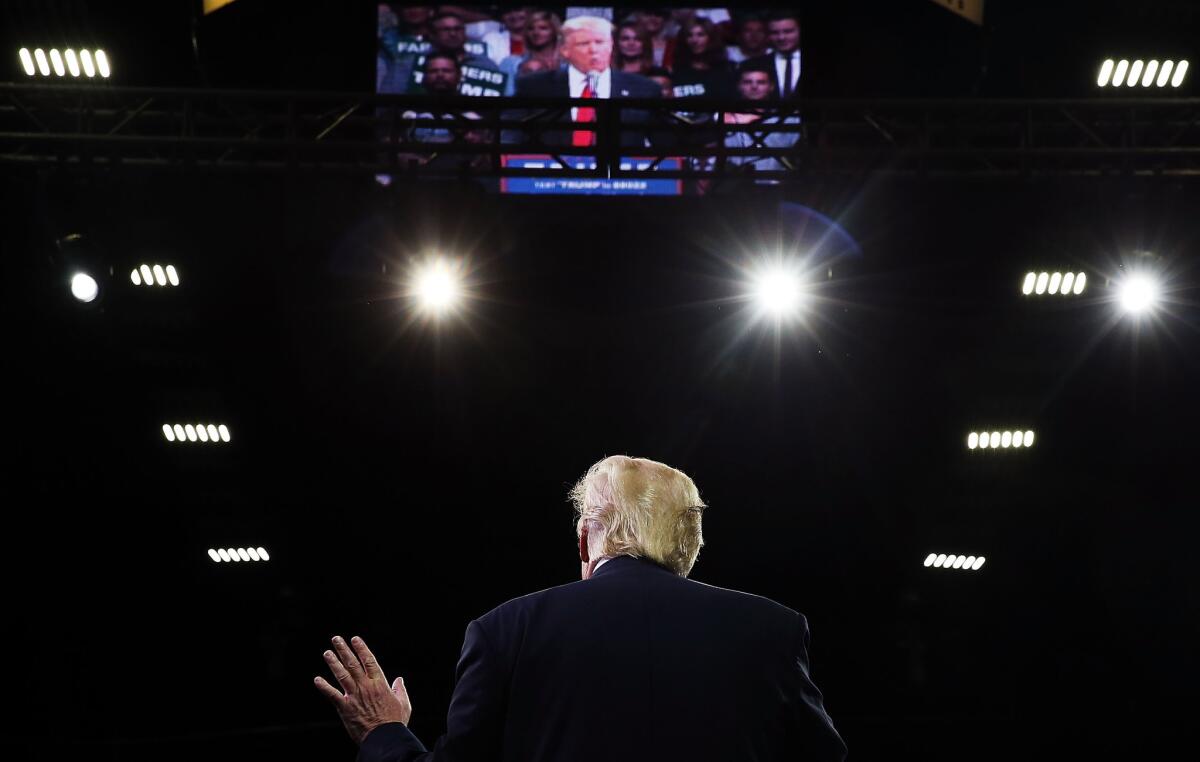

The most popular candidate among white American men is a parody of American manhood. By now, we have become used to the frat-boy performance that defines Donald Trump’s candidacy: the sexual boasting, the condescending or outright insulting treatment of women, the open discussion about the size of his penis. As we approach the general election, it becomes ever more clear that Trump’s flagrant and empty machismo is not a distraction from his campaign but its substance.

Trump’s appeal cannot be ideological; that’s a given. Technically Trump represents the Republican Party, and Republicans will form his base of support in November. But he doesn’t endorse traditional Republican policies and several key members of the conservative intellectual class have described him as a fascist. Certainly he is not a Democrat either. His basic political incoherence has driven his style into the foreground.

When I look at Trump, I see a desperate attempt to recover from failed manhood. His hair alone is an icon of vapid masculine braggadocio. And the more closely I examine Trump’s masculinity, the more hollow it appears. I know it’s a small point, but several men have brought up to me how strange it is that Trump does not seem to know how to wear a tie. He uses an old-fashioned Windsor knot, and its tip always hangs about 4 inches below his belt.

These subtle gestures are the secret to his success: He represents masculine overcompensation, and masculine overcompensation is what lifts him.

The theory of masculine overcompensation has been well-established for decades, going back to Sigmund Freud’s notions of “reaction formation” and “defense mechanisms:” When men think their masculinity is in doubt, they respond by emphasizing traditional masculine traits.

In 2013, a group of sociologists put this theory to the test. “Overdoing Gender,” a study for the American Journal of Sociology, looked at how men and women reacted after they were given feedback suggesting that they were demonstrating masculine or feminine traits. The gender difference was dramatic. “Women showed no effects when told they were masculine; however, men given feedback suggesting they were feminine expressed more support for war, homophobic attitudes, and interest in purchasing an SUV.”

American men, in selecting Trump, in supporting Trump, are also overcompensating.

The same study revealed similar connections between threatened masculinity and “support for, and desire to advance in, dominance hierarchies” and “belief in male superiority.” The researchers even found a possible biological basis for overcompensation: “Higher testosterone men showed stronger reactions to masculinity threats than those lower in testosterone.”

Trump is a walking symbol of “overdoing gender.” He is threatened masculinity personified — a balding man who owns the most radical comb-over in history, a man who told one magazine profiler that the only company he enjoyed was “a total piece of ass,” a draft dodger who openly considers the possibility of using nuclear weapons in the Middle East and killing the families of terrorists.

American men, in selecting Trump, in supporting Trump, are also overcompensating. A revolution in gender relations is underway and traditional notions of manhood, both economic and cultural, have been threatened.

Women are close to earning 60% of undergraduate degrees and are now 40% of breadwinners in American families. The redefinition of sexual assault on the basis of affirmative consent and the rise of transgender rights are altering the oldest assumptions about the nature of men and women. A reaction was probably inevitable. Political progress generates countermovements, and the grand political movements of our time occur on the level of identity. Therefore new monsters of identity reaction rise up. Therefore Donald Trump.

Unfortunately, the authors of “Overdoing Gender” do not provide a solution to masculine overcompensation; rather, their solution is on an individual level, not a social one: “Perhaps the most successful way for men to disguise their masculine insecurity would be to behave in the same way as unthreatened men do.”

But it’s hard to imagine a general application of the researchers’ wisdom.

Even acknowledging the threat to masculinity would require overcoming the sense of threat that causes the compensation in the first place. The threat to masculinity causes men to declare more and more vociferously how unthreatened they are.

A saving level of introspection may be too much to hope for in 2016. It’s rare enough with individual men, never mind the American electorate.

Stephen Marche is a novelist and a culture columnist at Esquire magazine. His most recent book is “The Hunger of the Wolf.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.