Op-Ed: As a medical student, I was told we had conquered measles. I wish

- Share via

In the 1980s, when I was a medical student and later a pediatrics resident, grizzled old pediatricians would tell us how lucky we were that we’d probably never see a case of measles or diphtheria or polio. Images and descriptions of these diseases were still classic favorites on medical board exams, though, so we dutifully committed information about them to memory. That was a good thing.

In January of 1988, I was a resident at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, assigned to a month in the emergency department. Winter was always busy, with patients waiting hours to see a doctor. Many of the cases were not really emergencies, but children brought in by indigent parents who had no access to primary care. The range of illnesses we saw in the emergency department taught a skill crucial to being a pediatrician: how to distinguish a very sick child from a not-so-sick one.

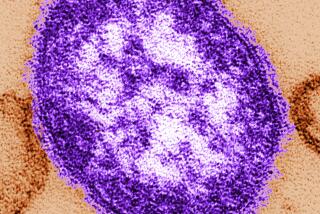

I was plowing through a typical caseload one night, which went something like this: ear infection, ear infection, stitches, asthma attack, ear infection … and then I went into a room where a baby, maybe 8 or 10 months old, had a rash and a fever and a runny nose. The mother was distraught. I examined her and the “very sick” alarm went off in my mind. And something else, too — a memorized textbook picture of measles.

California has some of the strongest laws of any state promoting vaccinations, but we can do even better.

I excused myself and went to find the senior resident. “I think this baby I just saw has measles,” I said. “Can you come and take a look?”

He laughed. “It’s not measles. But I’ll be glad to see your patient.”

He followed me into the room, and his expression changed. We went to get the emergency medicine fellow. And then the attending physician. And then an infectious disease specialist, who drove to the hospital at 1 a.m..

Dr. Harry Wright, the specialist, was old enough to have seen children with measles. He examined the child and called us around him. “Do you see these spots inside her mouth? They’re called Koplik spots.” That sign is unique to measles. It couldn’t be anything else.

The child was admitted to the hospital, the first of many over the following months, because measles brings with it complications, including ear infections, pneumonia, brain swelling, and death.

During that measles epidemic, which raged in California from 1988 to 1990, every intern and resident became adept at recognizing measles. There were 16,400 cases of measles in California alone. More than 3,000 children were hospitalized, and 75 died. The cost of containing the California outbreak and providing care to those infected was estimated at more than $30 million.

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases in existence, spread by airborne droplets. Someone who has measles can sneeze in an empty room and infect an unvaccinated person who walks into that room two hours later. Nine out of 10 unprotected people who are exposed to the virus will be infected. This is why “herd immunity,” protection that occurs when a high percentage of the population is immunized, is so important.

Not everyone responds to vaccination, and babies under 6 months old, as well as those with certain medical conditions, cannot be inoculated. These people are at risk during an outbreak, and we as a society have responsibility for ensuring their safety by doing all we can to achieve universal vaccination.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

In the aftermath of the 1988-90 epidemic, efforts were made to increase herd immunity: A schedule of two measles vaccines was recommended instead of one, private insurers were required to cover vaccination and efforts were undertaken to reach high-risk populations.

Last week the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported measles infections in 704 people across 22 states, including California, the largest number of cases in 20 years. Anti-vaccination sentiment, which has been around in one form or another since the smallpox vaccine was introduced 150 years ago, is playing a larger role this time. In 1988 there was no internet, no Facebook, no Google and no social media anti-vaccine campaigns. Older approaches to comprehensive immunization are no longer enough.

California has some of the strongest laws of any state promoting vaccinations, but we can do even better. We can support the passage of SB 276, which aims to eliminate bogus medical excuses. We can change adolescent self-consent laws, which currently allow minors over 12 to consent for hepatitis B and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, but not for other vaccinations. (Those two are covered under self-consent in order to aid prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections).

We can share personal stories about people who suffered from vaccine-preventable illnesses, including measles. And each of us can make sure our family members are vaccinated.

Linda Schack is an adolescent medicine specialist practicing in Torrance.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.