Op-Ed: Looking Ebola in the eye, with help from Camus

- Share via

Ebola’s exponential growth and extraterritorial reach has caused commentators across the ideological spectrum — from former U.S. Central Command chief Gen. Anthony Zinni to the Daily Kos — to describe the spread of the virus as an “existential threat.” For liberals and conservatives alike, “existential” is a nuts-and-bolts adjective relating to the existence of the human species. Who doesn’t agree that, if left unchecked, Ebola poses an “existential” menace because it threatens our collective existence?

But dress the term in a trench coat and give it a Gauloise to smoke and, voilá, “existential” means something more. It begins to speak with a French accent — specifically, the Mediterranean accent of Albert Camus. The Nobel Prize-winning writer was not a doctor or an epidemiologist, and works of literature are not practical or ethical instruction booklets. Yet Camus has much to say about the Ebola crisis.

In 1947, Camus published “The Plague.” The book is less a diagnosis of the bubonic plague — the disease of its title — than it is of the totalitarian plagues of the 20th century. With Nazism just extinguished and communism newly resurgent, the book became a bestseller. Its popular success, along with the critical success of “The Stranger,” published during the German occupation, made Camus into the poster boy for French existentialism — a term Camus always rejected, but that nevertheless clings to his life and work.

The novel’s plot is simple: Bubonic plague strikes the Algerian city of Oran. Quarantined and isolated from the rest of the world, the city’s inhabitants at first struggle to accept their transformed reality, then seek ways to resist. Given the force of the disease’s spread — the body count climbs relentlessly during the torrid summer months — resistance seems futile. Even the novel’s narrator, the dedicated Dr. Bernard Rieux, downplays the impact of the sanitation teams in Oran in stemming the plague’s advance.

No doubt, were he alive today, Camus would recognize the heroic work undertaken by Doctors Without Borders at limiting the spread of Ebola in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. (The group’s president, Joanne Liu, recognizes in turn the work of Camus: “The Plague” is one of her favorite books.) But Camus would praise Doctors Without Borders for other reasons as well, reasons that have less to do with material than with moral prophylaxis. Its actions reflect the decency and determination that mark the small band of rebels — the resistance — in “The Plague.”

When we gaze at the linguistic rubble of public misstatements made by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the World Health Organization responding to the Ebola crisis, we should not be surprised to learn that speaking clearly and honestly is an ethical duty for Camus’ heroes. The man responsible for organizing the sanitation teams, Tarrou, insists that all of humankind’s troubles “spring from our failure to use plain, clear-cut language.” Similarly, Rieux strives for objectivity so as “not to play false to the facts, and not to play false with myself.” This explains his impatience with the city’s authorities, who treat the word “plague” as if it were the plague. When one official remarks that the soaring mortality rates are merely “perturbing,” Rieux explodes: “They’re more than perturbing; they’re conclusive.”

As someone who “recognizes what has to be recognized,” Rieux’s attention to language is mirrored in his attention to his fellow men and women. He attends to them as individuals with whom he is condemned to live. This is the same attention demanded by Liberians who take snapshots of themselves holding signs that read “I am a human being, not a virus.” This demand also reflects Tarrou’s austere affirmation that the world is made up of only pestilences and victims, and our duty is not to join forces with the former.

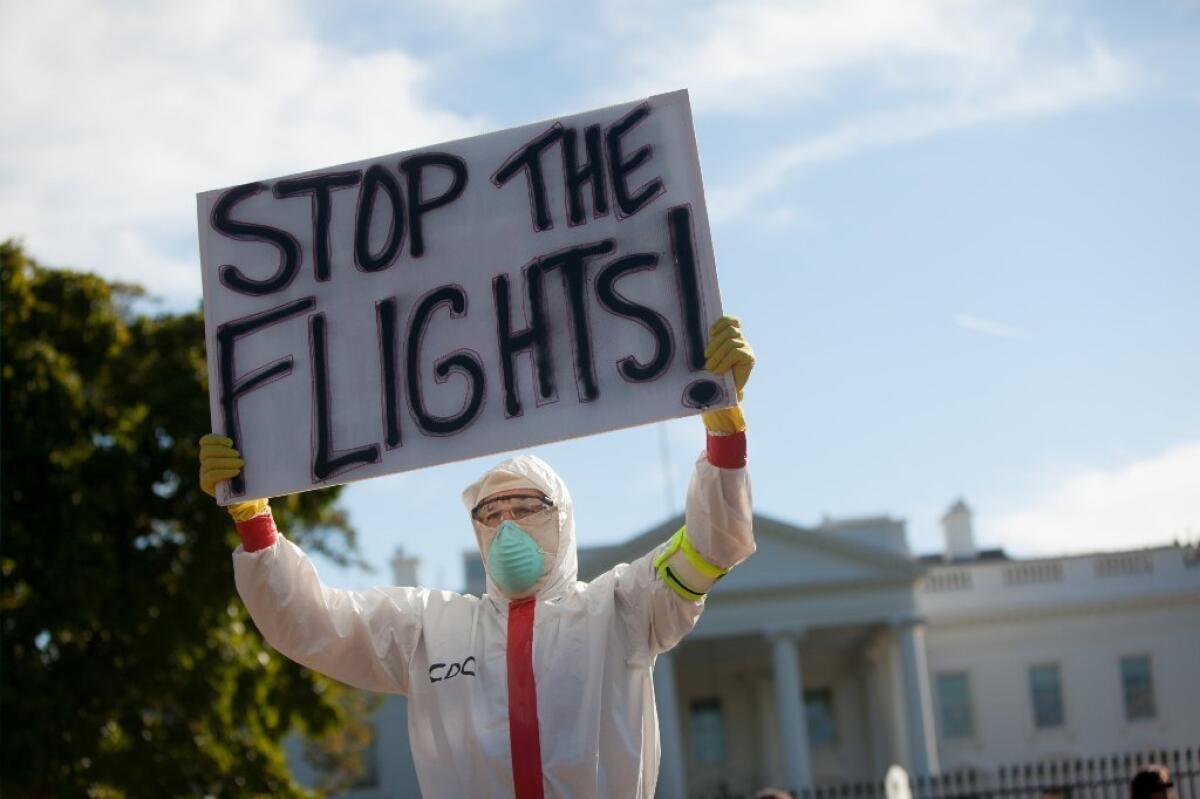

In today’s world, veined with webs of transportation and information, just as in the smaller world of Camus’ novel, we are all in the Ebola crisis together. The tragic confusion early on at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, followed by the quarantine missteps and the latest news from New York, reminds us there is no absolute escape from such a disease — and all the other plagues that can go viral around the world.

Yet there are always those who try to escape the inescapable. A Parisian journalist in the novel, Rambert, finds himself in Oran when the plague arrives and the city is quarantined. Trapped, Rambert tries to persuade Rieux to help him leave: “I don’t belong here,” he tells the doctor. Rieux’s reply: “Unfortunately, from now on you’ll belong here like everyone else.”

In the end — in Oran and in the Ebola crisis — there is the realization that this world and its cargo of passengers is all we have, all we have ever had. We either stand and fight, even in the face of inevitable loss, or we capitulate. When Rambert finally has the chance to leave Oran, even he has learned this lesson. He chooses to remain. Puzzled, Rieux asks him why. “I cannot leave,” Rambert says, “now that I have seen what I have seen.”

We cannot “leave” Ebola; we cannot escape the plague. But as Camus tells us — and what is truly existential — we still need to make the choice to remain.

Robert Zaretsky teaches in the department of modern and classical languages at the University of Houston and is the author of “A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.