Opinion: Advocates of easier voting should make an ‘advantage’ argument

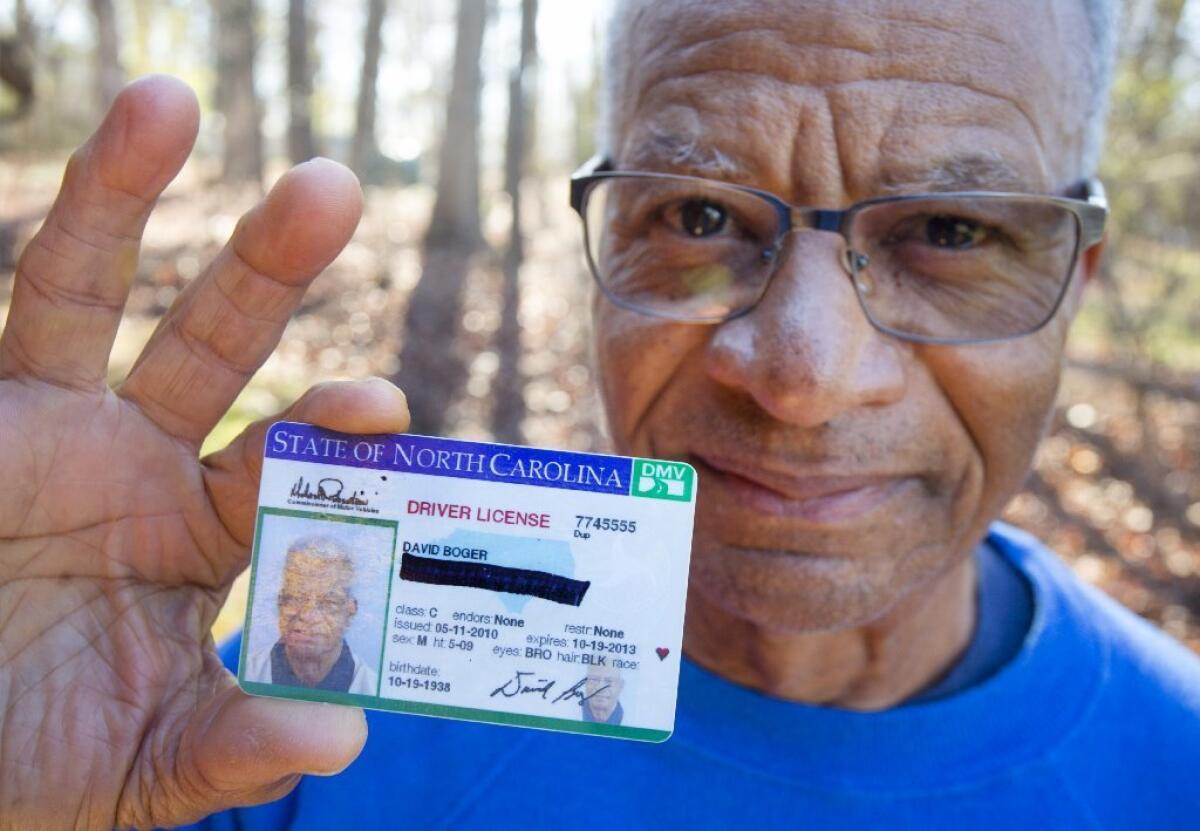

David Boger blacked out his address on a driver’s license to protest North Carolina’s voter ID law as he cast his ballot in Greensboro, N.C., on March 15.

- Share via

Recently I returned to my high school in Pittsburgh for a reunion of its storied speech and debate society (officially known as the Central Catholic Forensic Society, which sounds as if it’s training teenage crime scene investigators).

Reminiscing about my debating days reminded me of a distinction that seems relevant to the debates over “voter suppression” — a term I place in quotation marks because it’s used to refer to different things.

Everyone agrees that it was voter suppression for Southern states to require that African Americans pass a literacy test in order to vote. But the term is also used, at least by Democrats and editorial writers, to describe photo ID requirements and the rollback of procedures that made voting more convenient, such as early voting and Sunday voting.

The debate over “voter suppression” — which is in the news this week with a federal judge’s decision to uphold what some call a voter-suppression law in North Carolina — would benefit from a distinction drawn by high school debaters between two arguments.

In competitive debate, the Affirmative team supports some resolution about public policy such as “Resoled: The Military Draft Should Be Reinstituted.”

In making its case, the Affirmative can take one of two approaches.

Option 1 is to point to “harms” in the status quo that approval of the resolution would alleviate (say, crimes committed by teenage gangsters who would be taken off the street and whipped into shape by drill sergeants).

Option 2 is to offer a “comparative advantages” case, one that says that, while things might not be all that bad now, we’d be much better off if the debate resolution were adopted. (A draft would bring young people of different socioeconomic backgrounds together to fight the enemy, or at least peel potatoes.)

The 1965 Voting Rights Act was clearly inspired by a “harms” analysis: Racial minorities were being frustrated in exercising the right to vote by laws and procedures that violated the letter and the spirit of the 15th Amendment, which banned racial discrimination in voting.

In time, as the Voting Rights Act was extended and amended, the “harm” was conceived more broadly to include the dilution of minority voting strength through redistricting and procedures that had the effect of undermining minority voting even if that wasn’t their intent.

Recent voting-rights litigation is couched in terms of harms, as it must be. But reading Judge Thomas D. Schroeder’s decision in the North Carolina case, it strikes me that some of the objections to supposed voter-suppression laws are more plausibly viewed as “comparative advantage” arguments.

Schroeder rejected the claim that minority voters were illegally disadvantaged by a law that required photo ID (except for voters who could cite a “reasonable impediment”) and rolled back some provisions that made voting more convenient. For example, the law reduced the number of early voting days from 17 to 10, although the numbers of hours the polls must open didn’t change.

The plaintiffs disagree with the judge’s conclusion and are appealing. Fair enough. But it’s possible that reducing the number of early voting days is both bad policy and not a violation of the Voting Rights Act or the Constitution.

Instead of reducing the number of early voting days from 17 to 10, perhaps North Carolina’s Legislature should have increased the number to 20 or 30 or even 50. Even if more early voting days wouldn’t appreciably increase turnout, they would make voting more convenient.

Likewise, it may be a good idea to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to pre-register for elections in which they can participate once they turn 18 — as they could under a previous North Carolina law. But that would be true regardless of whether abolishing such preregistration meets the legal test for discrimination because it has a racially disparate effect.

Even if Congress votes to reconstitute the Voting Rights Act and set new standards for preclearance, some election regulations will be upheld by the courts regardless of whether they are bad policy (or politically motivated) and make voting more difficult.

Maybe voting-rights activists should talk less about debatable legal harms and more about the comparative advantages of voter-friendly election laws.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.