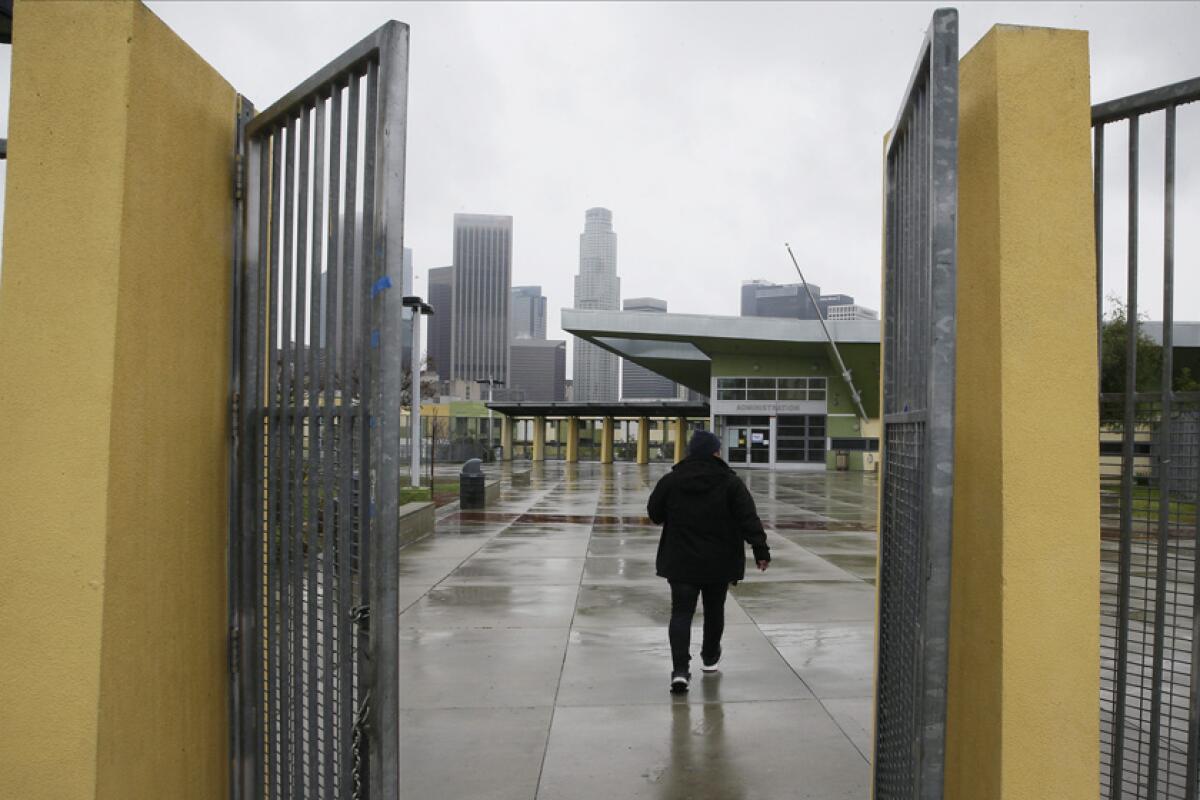

Editorial: The new school year is starting, ready or not. Much of California is not

- Share via

Most California schools are a week or two away from the start of the school year, which will be conducted online for at least 80% of them. Yet many are still trying to hammer out agreements with their teachers unions about what the school day will look like. How many minutes of live instruction will students receive? How many minutes of recorded instruction? How much small-group work with a teacher, or one-to-one contact?

The results have been all over the map. San Diego Unified students will get about 30% more live, real-time instruction with a teacher than those in the nearby Sweetwater Union district, and nearly twice as much as in Los Angeles Unified. Oakland still hasn’t reached an agreement with teachers, or fully trained them, even though it’s supposed to begin school Monday. They can’t get lesson plans going if they don’t know how much teaching will be live and how much recorded.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom should have stepped into this fray with a heavy foot from the start. The Legislature, at least, set a minimum number of instructional hours — and required daily attendance and grades — but for the most part left it to school districts to decide exactly what instructional time meant.

That time could mean back-and-forth among students and teachers in a live, interactive virtual classroom, which is generally considered the most effective. It could mean recording video lessons for students to view on their own, which gives both teacher and student more scheduling flexibility. Or students could be doing assignments outside the class setting, like homework. Some schools are adding time for small-group instruction or individual tutoring; others are not. Most will do some combination of the above but in differing amounts.

School boards and their superintendents needed clear direction, not the figure-it-out-yourselves philosophy that’s been coming from Sacramento and Washington. Having gotten no such guidance, schools are struggling to come up with their own scenarios and to negotiate those with sometimes reluctant unions. The result is a patchwork in which some students in the state will receive more and better education than others, and that’s unacceptable.

Without being too prescriptive, state leaders should have averted this situation with laws, regulations and firm admonishments so that schools, teachers and parents knew what to expect and would have been able to avoid the last-minute wrangling. Let’s face it — for most students and parents, last spring was a learning disaster. But that stemmed from the sudden, unforeseen hammer of the COVID-19 pandemic. By now, all school districts should have their training done, their remote classrooms set up and their schedules out to parents so families can be ready for the demands of the new school year.

State Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond has no authority to impose instructional mandates on school districts, and Newsom’s emergency authority may be limited. But both could have demanded clearer requirements from the Legislature that would have bypassed district-by-district union negotiations, and they could have used the bully pulpit to push relentlessly for teachers to spend significant time interacting with students. Newsom even could have promised extra funding for schools that met his yardstick. Now, sadly, it seems too late.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.