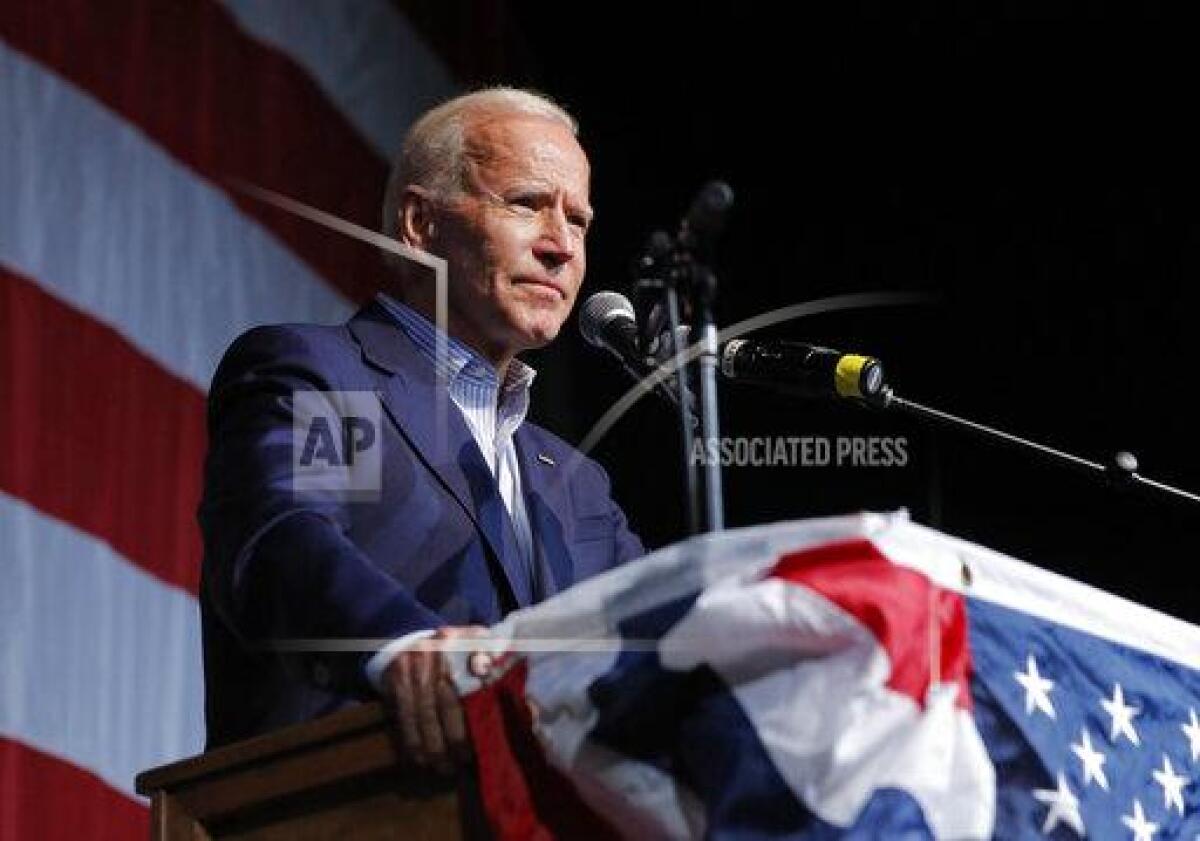

Opinion: Sign of the times: A bishop bashes Biden and Catholics object (or yawn)

- Share via

Joe Biden, who if elected would be the nation’s second Roman Catholic president, was bashed by a Catholic bishop this week, and a lot of Catholics either yawned or came to Biden’s defense. That says something about changes both in the American church and in the declining role of religion as a political identity.

Biden, who emphasizes his Catholic upbringing, has also moved to a pro-choice position over the years, most recently abandoning his support for the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funding for abortion in most circumstances. Presumably that was what motivated Bishop Thomas J. Tobin of Providence, R.I., to tweet this on Tuesday:

“Biden-Harris. First time in awhile that the Democratic ticket hasn’t had a Catholic on it. Sad.”

Put aside the illogic of the attack: Tobin seems to suggest that Biden isn’t a Catholic now, but was in 2008 and 2012 when he ran for vice president on a ticket with Barack Obama.

Although Biden’s change of heart on the Hyde Amendment is recent, he embraced Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion, as early as 2007. In that year, he said the ruling was “the only means by which, in this heterogeneous society of ours, we can reach some general accommodation on what is a religiously charged and a publicly charged debate.”

Oh, and John Kerry, the Democrats’ nominee in 2004, was also a Catholic supporter of legal abortion. Was Tobin counting him?

Tobin was upbraided on Twitter for his knock at Biden, including by Catholics who pointed out that it’s not up to Tobin to unchurch the former vice president. The prominent Jesuit writer James Martin tweeted: “Mr. Biden is a baptized Catholic. Thus, he is a Catholic.”

This isn’t the first time Biden’s Catholic bona fides have been challenged by a Catholic cleric. Last year, a priest in South Carolina said that he had denied the sacrament of Holy Communion to the former vice president because of Biden’s support for legal abortion.

But long gone are the days when a priest or a bishop could meaningfully damage the reputation of a Catholic politician — even among Catholic voters — by accusing him or her of unfaithfulness to church teachings. According to a 2019 Pew survey, 56% of U.S. Catholics believe abortion should be legal in most or all cases.

Mark J. Rozell, dean of George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and an expert on Catholic voting patterns, said in an interview that there was “no evidence that cues from church leaders in any way influence Catholic voters“ in the United States. Catholic voters, like other Americans, are “very independent-minded,” he said.

Rozell noted that in 2004 Catholic voters preferred Methodist George W. Bush to their fellow Catholic Kerry. He added that “this is not 1960,” when Catholic voters rallied around John F. Kennedy.

What about a cultural affinity between a Catholic politician and Catholic voters? Rozell suggested that Catholic identity might have only a marginal effect on such voters. They are more likely to focus on the issues, agreeing with a bishop’s pronouncement if it substantiates what they already believe.

That Biden has survived critiques of his Catholicism is a reflection of major changes in the American church. But this episode is a reminder of a broader phenomenon: the decline in religion as a proxy for political identity. Religious affiliation doesn’t seem to generate the same desire for representation as race or gender. Biden’s Catholicism hasn’t occasioned anything like the commentary that has focused on Kamala Harris’ gender and ethnicity.

The Almanac of American Politics still lists religious affiliation in its profiles of members of Congress. (Harris is described as a Baptist on Page 163 of the 2020 edition.) But that’s arguably a hangover from the days when religious affiliation was an important part of a politician’s brand. A lot of Americans feel an affinity with candidates who “look like me.” Not so much for those who “pray like me.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.