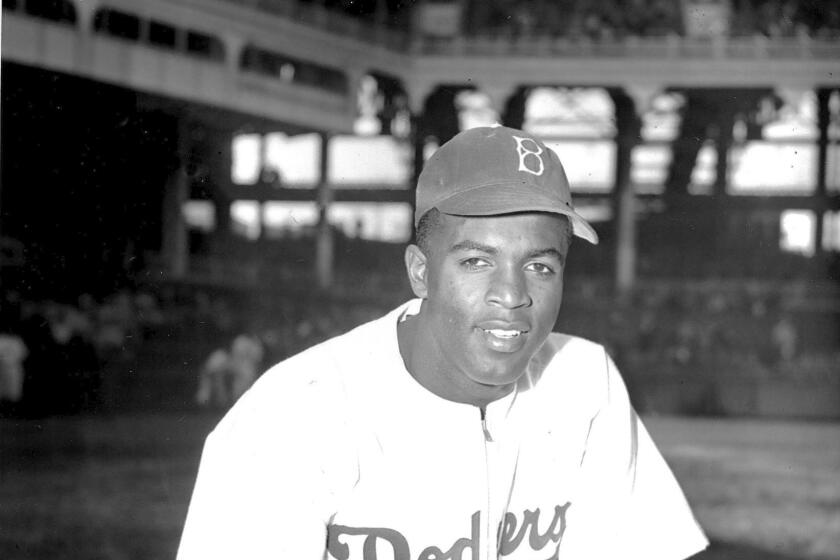

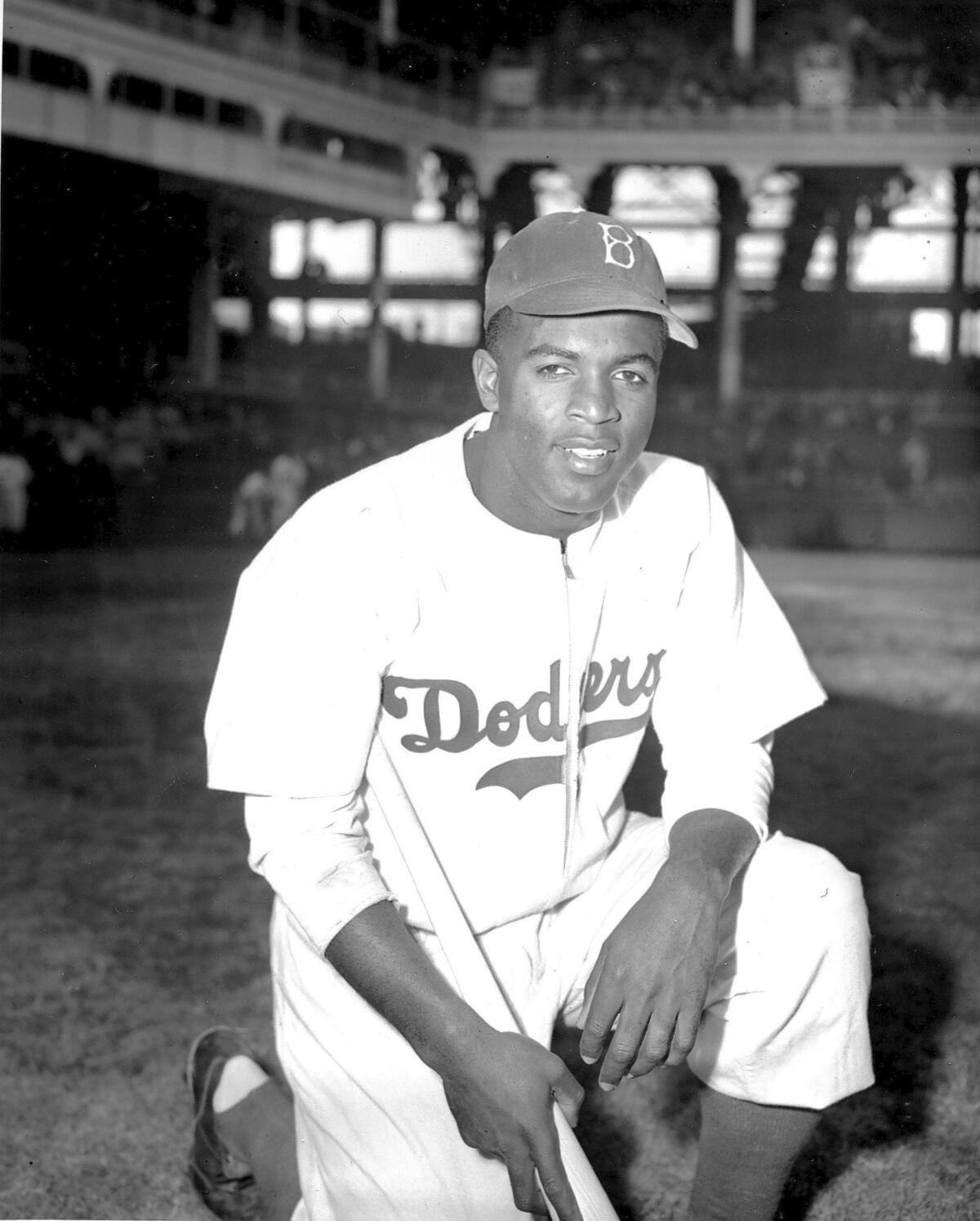

Op-Ed: Jackie Robinson didn’t just break barriers. MLB should honor his radical activism too

- Share via

Major League Baseball usually holds Jackie Robinson Day on April 15, commemorating the day in 1947 when he broke the league’s color barrier by become its first Black player. Since the coronavirus pandemic delayed this year’s season, baseball plans to honor him on Friday, the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington.

Postponing rather than canceling was the right thing to do, especially this year, as the country reckons with its racist past and present. Even more laudable would be a commitment from MLB to pay tribute to the militant Robinson rather than the nonthreatening Jackie it usually celebrates.

This is not the year for MLB to serve up yet another video montage or flowery speech praising Robinson’s nonviolent response to racist players, coaches and fans. That would be a slap to the Baseball Hall of Famer who dared to support the Black Panthers in their fight against police brutality. That’s right: The smiling second baseman who “turned the other cheek” became a fierce supporter of the radical Black group as they battled the men in blue.

On Aug. 21, 1968, three Black Panthers in New York City were arrested and charged with assaulting a white police officer. At their hearing two weeks later, about 150 white men, including off-duty and out-of-uniform police officers, stormed the courthouse and attacked 10 Panthers and two white supporters. No arrests were made in the aftermath, even though uniformed police officers had witnessed the beatings.

Robinson had long condemned police brutality in his syndicated newspaper columns, and he was so livid about this most recent beatdown that he visited the Panthers at their headquarters in Brooklyn on Sept 12. Just before the meeting, he held a news conference in which he lambasted police brutality and praised the Panthers.

Ken Burns has added another face to the metaphorical Mt.

“Improper reporting has determined that they are a militant group while the fact is that they are seeking peace,” Robinson said. “The Black Panthers seek self-determination, protection of the Black community, decent housing and employment, and express opposition to police abuse.”

Of the courthouse attack, Robinson said the Panthers “had every reason to be violent after that kind of violence,” and that the offending officers “should have been arrested then and there.” He also criticized officers who were “trigger-happy,” and even suggested that he might have joined the Panthers if they had been around when he was a teenager.

Robinson’s support for the Panthers was consistent with his earlier backing of another controversial group — the Deacons for Defense and Justice. Founded in Louisiana in 1964, the Deacons emerged out of frustration with white law officers who failed to protect Black lives. Group members were armed and committed to shooting racists who threatened the lives and property of innocent Black people.

Although Robinson said he preferred the use of nonviolence in the campaign for civil rights, his stance wavered. His views never quite aligned with those of his good friend, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. This was especially clear in 1963 when King invited Robinson to speak to Birmingham, Ala., activists after they had been brutalized by Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor and his troops.

“You can love them if you want to, but me, I simply can’t do it,” Robinson told the protesters. “It’s not in my nature.” A reporter noted that King had a pained look when his friend delivered those memorable lines. But Robinson was “not nonviolent,” as he put it, and he long believed it was morally justifiable for Black people to defend themselves, especially when white police officers ignored or battered them.

In 1971, Robinson had his own brush with police brutality when he sought to enter the Apollo, the Harlem theater famous for showcasing Black talent, for an afternoon visit with friends.

As he told the story, “On my way into the lobby, an officer, a plainclothesman, accosted me. He asked me roughly where I was going, and I asked what the hell business it was of his. He grabbed me and spectators passing by told me later that he had pulled out his gun. I was so angry at his grabbing me and so busy telling him he’d better get his hands off me that I didn’t remember seeing the gun. By this time people had started crowding around, excitedly telling him my name, and he backed off.”

Robinson escaped physical harm and later realized that the spectators — and his name — had saved him. “Thinking over that incident, it horrifies me to realize what might have happened if I had been just another citizen of Harlem,” he said. “It shouldn’t be necessary to be named Jackie Robinson to keep from getting brutalized.”

Yet here we are, almost 50 years later, protesting police brutality targeting Black people whose names are not Jackie Robinson: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others.

If Major League Baseball is serious about honoring Robinson in this historic moment, all it has to do is follow in his footsteps: Meet with Black Lives Matter leaders, denounce police brutality, demand police reforms, honor Black victims, give generously to Black communities in need — and then do it over and over again. Otherwise, this year’s Jackie Robinson Day, like all the others, will be more about MLB’s front-office whiteness than the proud Black man who helped transform baseball, and subsequently, America.

Michael G. Long is the editor of the forthcoming “42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.