Editorial: Another sign of the times: Mass shootings are spiking

- Share via

Sometime in the dark hours of a recent Sunday night, gunmen opened fire inside an illicit marijuana farm in Riverside County, killing seven people. It was, according to data maintained by the Gun Violence Archive, the 28th mass shooting in California since the beginning of the year, part of a nationwide anomalous trend: While overall violent crime has edged downward this year, homicides have increased in several major cities, including here in Los Angeles.

There also has been a spike in mass shootings (defined as single events in which least four people are wounded or killed) that began in the summer. At around 400 incidents, the number has already surpassed the annual totals in three of the last four years, according to an analysis by online news site the Trace.

Why is this happening? Some experts point to tensions arising from coronavirus pandemic lockdown policies, but they say too little data are available at this point to properly frame the issue. The Trace also reports another troubling reality: Through Aug. 24, nearly half of the nation’s mass shootings occurred in majority-Black census tracts, even though fewer than one in 10 tracts are majority Black.

Experts believe the pandemic has exacerbated the preexisting social problems that feed violence in certain areas — the lack of jobs and educational opportunities, reduced access to mental health care and other services and, now, an overlay of social isolation that can bring simmering personal conflicts to a full boil. Mass shootings often begin as domestic disputes, or confrontations among acquaintances. In fact, the Everytown for Gun Safety advocacy group reports that for the decade ending in 2018, six in 10 mass killings (defined as at least four people dead excluding the shooter) occurred in private homes.

Those domestic mass shootings don’t grab the public’s attention like a school, church or workplace shooting, where the death tallies have been numbingly high. And perceptions of the nature of the violence influences the public response. White males account for the majority of mass shooters, but when one locks his family in the house and then kills them before killing himself, it doesn’t draw the same reaction from media or the public as when someone shoots up a school or a church. Mass shootings in low-income, nonwhite neighborhoods perceived by white society to be prone to violence get shrugged off, too, though the pain and anguish are no less. And if there is a clear crime nexus — a gang shooting, or the massacre of seven people at an illicit Riverside County pot farm — public interest is fleeting.

Yet mass shootings have similarities. As the American Psychological Assn. points out, men commit the vast majority of gun violence, but a vast majority of men do not commit such acts. Remedies must focus on those who turn to violence as a perceived solution, and that requires, among other tactics, providing programs in schools and other settings designed “to change gendered expectations for males that emphasize self-sufficiency, toughness, and violence, including gun violence.”

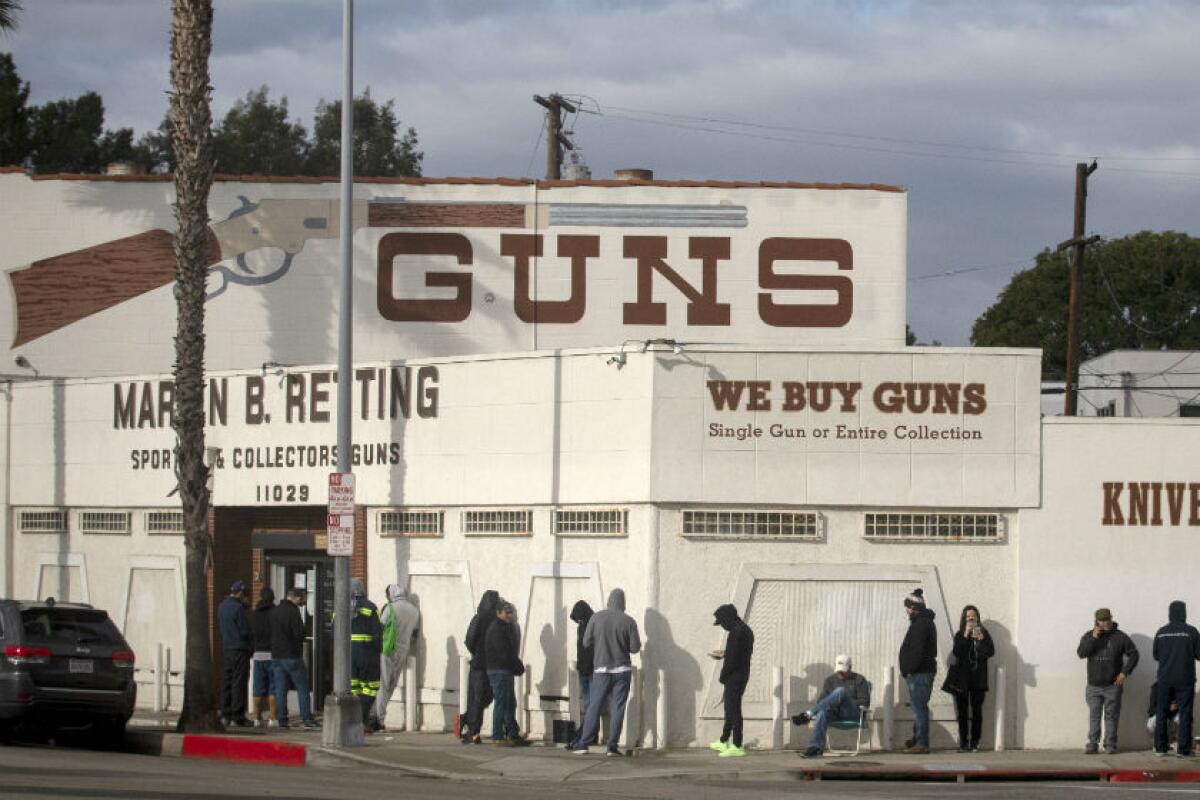

Of course, there would not be mass shootings were it not for the presence of guns, and so far this year there also has been a surge in gun sales. Through the end of August, the Federal Bureau of Investigation processed nearly 26 million firearm background checks — a loose proxy for gun purchases — which is more than it processed in all of 2017. From 2017 to 2019 it averaged more than 2.2 million background checks a month. So far this year, the rate has jumped almost 50%.

Usually such leaps come when people fear that the government is poised to make it harder to buy guns, often after high-profile mass shootings at schools, churches or other public places. But according to a Brookings Institute report, a propelling factor this year is personal fear arising from the pandemic, augmented by reactions to political unrest and demands for defunding police in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

So partway through the pandemic, this is where the nation finds itself — with increased stress, a greater sense of personal isolation, elevated gun sales and less access to jobs and support systems apparently fueling more mass shootings. We can only hope that the pandemic will pass and that the stresses feeding this violence will fade away. But then we’ll still have the guns, and the structural racism, and a body politic that has proved incapable of taking the steps necessary to reduce access to firearms while increasing access to the jobs and social services the experts keep telling us are necessary to reduce gun violence.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.