Op-Ed: There are racial disparities in American unemployment benefits. That’s by design

- Share via

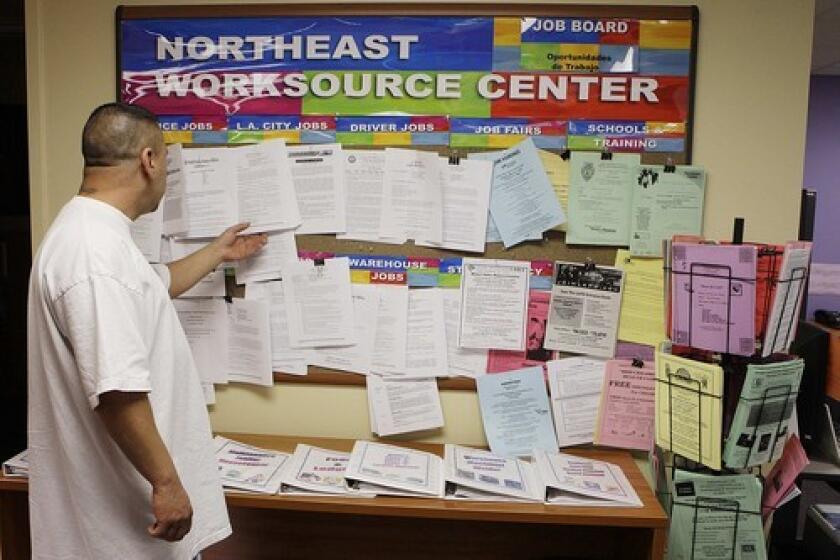

Unemployment insurance is serving a vital role in stabilizing the economy and supporting the households of 25 million workers. At the same time, its failings have been on display.

Florida started the recession with a computer system that appears to have been designed to discourage applications. The maximum benefit offered by 14 states is not enough to replace 50% of wages for the average high school graduate. Seventeen states have depleted their trust fund and have had to get loans from the federal government.

There’s a longstanding accusation leveled at the country’s unemployment insurance system that has been revived lately — that it’s structurally racist, deliberately discriminatory from the outset and remains so today.

The claim has been met with doubt. Some suggest that the disparity in benefits available to Black and white Americans is skewed by lower wages in the American South, where a large share of Black workers live. Other skeptics have argued that Black workers wait longer for benefits and are less likely to receive them because they are disproportionately low-wage workers, and unemployment insurance has minimum earnings requirements. It’s not intentional that Black workers benefit less; it’s incidental.

But underlying the debate is a legitimate question: Why doesn’t unemployment insurance treat all workers and all earnings the same?

California should replace outdated technology and overhaul poor policies that have delayed unemployment benefits to those left jobless during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a strike team appointed by the governor.

Both “old-age insurance” — what we call Social Security — and unemployment insurance were created with the Social Security Act, passed by Congress in 1935. The federal government would run the old-age program, while states would run the unemployment program. Both were social-insurance programs, meaning that workers paid into trust funds via a payroll tax, and this made them eligible for benefits. Both programs excluded certain occupations, including domestic workers and agricultural workers.

Excluding domestic and agricultural workers from the unemployment program was to the detriment of Black people, most of whom lived in the South. This much is widely agreed upon. By virtue of their occupations, about 65% of Black workers at the time fell outside the act, compared with 27% of white workers.

Seventy-five years after the bill’s passing, the Social Security Administration offered a detailed explanation for why excluding the majority of Black workers was not the result of “prevailing racial biases.”

The agency’s case goes like this. The bill also excluded many white workers, women and other groups, including Latino and Asian workers. Most unemployment compensation programs in other countries in the 1930s excluded agricultural workers. Moreover, the federal government was enacting programs on a scale never before done. There was almost no history of federal benefits of any kind. In short, there was no racial motivation to the design of the legislation; it was administrative necessity.

The counter-argument goes like this. There was racist intent behind the exclusions, and it is evident in a political devil’s bargain that Northern Democrats made with Southern Democrats. In order to get enough votes in Congress to pass most New Deal legislation, Northern Democrats had to give Southern Democrats the means to exclude Black people from receiving benefits. An economically empowered Black worker posed a political threat to Southerners and an existential threat to segregationist social structures. The bill was designed to exclude Black workers and enable Southern states to further exclude them; it was political necessity.

Of course, it could have been both administratively and politically advantageous to leave Black workers behind — which happens to be precisely what Black advocates said at the time.

As the bill was being debated, Charles Houston, representing the NAACP, testified in front of the Senate. Houston made it plain to Congress that it was deliberately excluding Black workers. “From a Negro’s point of view,” he said, “it looks like a sieve with the holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.”

George Haynes, of the Federal Council of Churches, also testified before the Senate. He pleaded with Congress to prohibit racial discrimination in the administration of the benefits. He presented data — tables documenting federal funding for universities, vocational education and earlier New Deal programs — as evidence of racial disparities. “There has been repeated widespread discrimination on account of race or color,” Haynes said, “as a result of which Negro men and women and children did not share equitably and fairly in the benefits accruing from the expenditures of public funds.”

Houston and Haynes made the same case. The design of unemployment insurance would prevent Black workers from obtaining benefits. The excluded occupations disqualified the majority of Black workers, particularly Southern sharecroppers. And allowing states to administer the benefits would only open the door for more discrimination.

The assessment that unemployment insurance is structurally racist is based not on the expressed animus of past lawmakers but, rather, on the design of the program and who it intentionally or incidentally leaves out.

There was no mistaking who the bill would leave behind. Congress had no intention of creating a program that treated white and Black workers the same. They didn’t miss the mark on racial equality. They weren’t aiming for it.

Kathryn A. Edwards is an economist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan Rand Corp. who researches labor and employment issues.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.