Column: Cannabis has downsides, especially for kids. We need to acknowledge them

- Share via

There was a time in my life, in the not-so-distant past, when cannabis was immensely important to me.

Not because I used it — I’ve tried it but don’t like the way it makes me feel — but because voters in California were being asked whether pot should be legal for adult recreational use. I took it upon myself to try to fully understand the upsides and downsides of Proposition 64, the 2016 ballot initiative, so I could help readers make informed decisions.

The No. 1 worry I heard then was the effect that legalization would have on children. In fact, my position is the same as the one voters embraced when they overwhelmingly approved legalization: No one under the age of 21 should use marijuana. Nor should children be bombarded with cannabis ads.

As it turns out, both of those things are widespread.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a small number of kids try pot in the eighth grade, but by the time they are high school seniors, nearly 44% will have tried cannabis. (That compares with 61% who will have tried alcohol.) So far it’s unclear whether teen usage rises when states legalize marijuana.

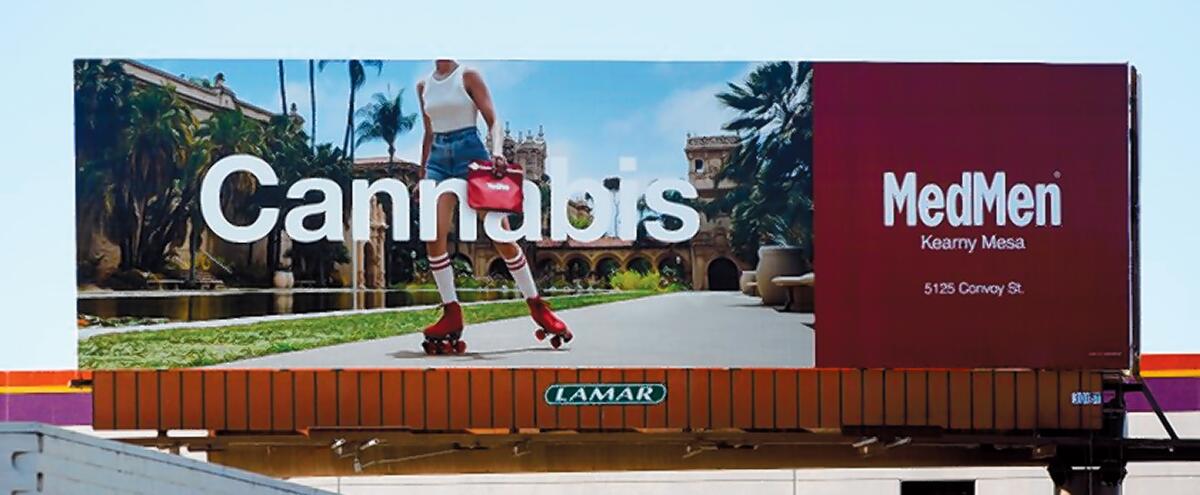

And just try to drive on any major thoroughfare without seeing billboards advertising cannabis brands, dispensaries and delivery services. The idea that kids are being protected from cannabis ads is laughable.

Last month, in fact, a San Luis Obispo County Superior Court judge ruled that the state Bureau of Cannabis Control had overstepped its authority when it decided to allow cannabis billboards along freeways.

The case, wrote my colleague Patrick McGreevy, was brought by a father of two who was alarmed by the cannabis billboards he saw as he drove with his kids on Highway 101.

I think the judge was right to ban the billboards.

Still, we have to acknowledge that cannabis, like alcohol, is a fact of life.

But it’s disingenuous to pretend that there is no downside to the drug, particularly when it comes to children, teenagers and very young adults. Heavy pot use among those whose brains are still developing is an invitation to disaster. And cannabis addiction is real.

Inevitably, when I write that I favor legalization, I hear from parents with horror stories about how cannabis has harmed their children.

Last week, in fact, after I praised the House of Representatives for voting resoundingly to decriminalize cannabis, I heard from several unhappy mothers. All of them believe that cannabis use contributed to the mental illness of their sons.

None wanted to be identified for fear of embarrassing or angering their children, but their stories were strikingly similar: Their sons began using cannabis as teenagers, experienced serious depression, anxiety or psychosis, and have been struggling ever since.

In one case, the mother believes that the pandemic exacerbated the problems of her son, a college freshman and athlete, who smoked pot because he was isolated and depressed about not being in class, making friends or playing his sport. He withdrew from school and asked his parents to find him help, which they have done.

Another mother reached out to tell me about her son, “who lives in a rusty van, has permanent psychosis and smokes marijuana every day.” He is in his early 30s, and has been mentally ill since he was 19.

Now, of course, anecdotes are not data. Correlation is not causation. And the medical benefits of cannabis for many conditions are indisputable.

But we do know that cannabis has a downside. Unsuspecting people who, say, ingest too many pot-spiked brownies and get stoned out of their minds often say they feel like they are dying. The good news is, they won’t die. Unlike alcohol and opiates, cannabis does not depress breathing and can’t kill you.

Cannabis use can also spark psychosis. For most people, a psychotic episode will be fleeting, and the symptoms will go away when the drug wears off.

But for those who have a genetic or biological risk for mental illness, as psychiatrist Thomas Strouse told me in 2016, heavy pot use could “hasten or intensify the manifestation, and lead to a worse course than if you never used marijuana at all.”

Strouse is medical director of UCLA’s Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital. I called him this week to ask whether the pandemic has led to an increase in cannabis-related psychotic episodes among young adults.

“The pandemic has been a disaster for mental health,” he said, but his staff has not seen an increase in cannabis-related psychosis among young people.

“It’s common for us to see a young adult presenting with a first psychotic episode,” said Strouse. “The 20s is the high-risk decade for new onset psychosis and schizophrenia. We do see pretty much every day young people with these symptoms.”

Severe mental illness can happen whether or not someone uses drugs, but experts say they often see people with mental illness who attempt to self-medicate with street drugs. “Crystal methamphetamine is the most common comorbidity,” Strouse said, “but many of these people are using multiple substances at the same time.”

In other words, it’s often hard to tease out which symptoms are caused by drug use and which by an underlying mental illness.

Years ago, I was on a panel at a cannabis conference, discussing how the media covers the industry. I made the point, as I often do, that legalization proponents were wrong not to acknowledge its drawbacks, especially for kids.

“F— you!” came a man’s voice from the back of the room. “Pot is the only thing that got me through high school!”

I would argue that he was one of the lucky ones.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.