Opinion: The Trump administration just executed its 13th person in six months

- Share via

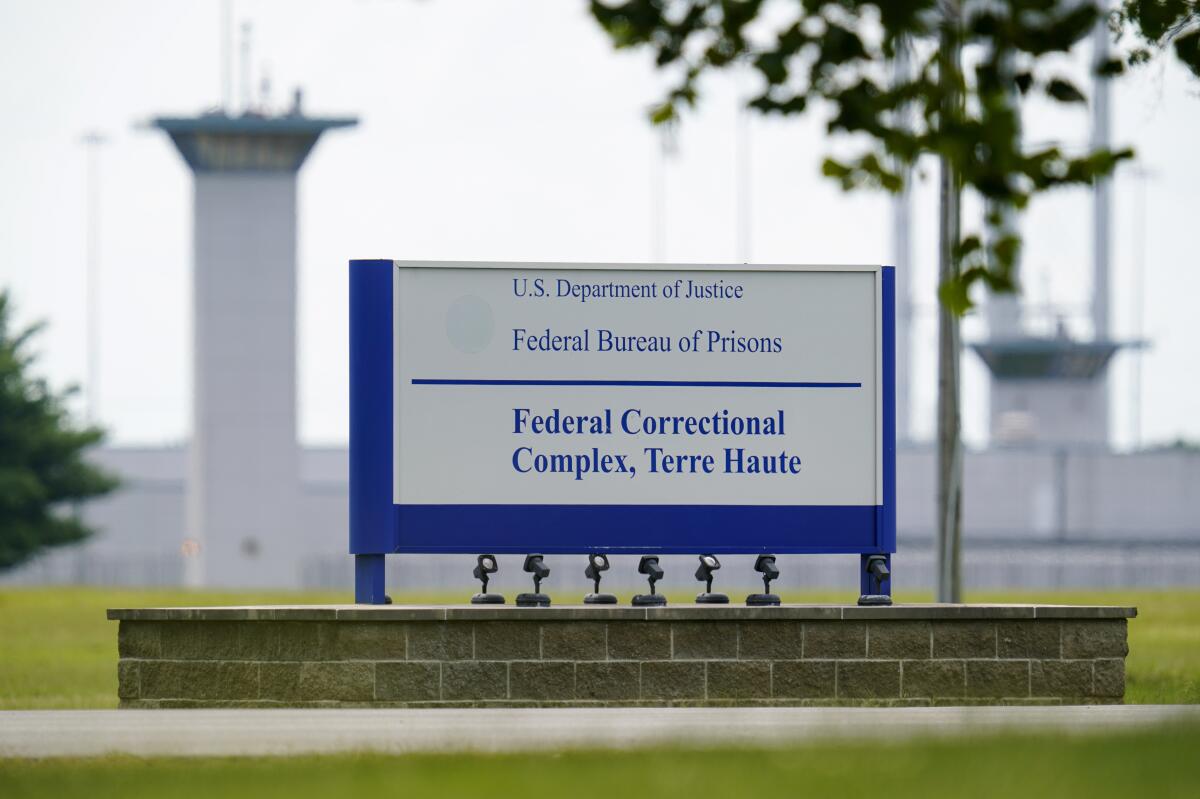

With the execution early Saturday of Dustin Higgs, the Trump administration ended a killing spree unrivaled in modern federal history.

Over a span of six months, it put to death 13 convicted murderers, more than four times the number of federal executions since the federal government reinstated the death penalty in 1988. And it was done primarily for politics.

Then-Atty. Gen. William Barr ordered the revival of federal executions after 17 years in July 2019 as President Trump — who supports the death penalty and, all personal evidence to the contrary, likes to portray himself as a “law-and-order” president — geared up for his reelection campaign.

And so people died.

Who did our government kill?

Anti-government sentiment has long been with us (no surprise for a country founded in revolution), but political violence is its most dangerous expression.

A woman who suffered horrific sexual and physical abuse for most of her life and had been diagnosed with a raft of mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder, dissociative disorder, psychosis and traumatic brain injury.

A white supremacist who played a lesser role in the murder of a family but was sentenced to death while the killer who orchestrated the crime received a life sentence.

A man who had been raped by his mother, struggled with a range of mental illnesses and, at the time of his execution, was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and had a questionable grasp of exactly why the government wanted to kill him.

Without a doubt the 13 executed prisoners — all but one of them men — had been involved in horrific crimes. The families, friends and communities of the murder victims deserve our support and sympathy for their understandable grief, anger and desire for retribution.

But executing the convicted perpetrators is not the right way to handle such crimes, as more and more people tell pollsters tracking the issue. If we sincerely believe that killing is morally wrong, it makes no sense to endorse it as a punishment.

And granting the state the power to kill individuals should give pause to anyone who fears an overreaching government, especially when the criminal justice system itself is so prone to error and manipulation.

We go to great and expensive lengths to, in theory, reserve the death penalty for the so-called “worst of the worst,” yet too often fail because the legal system cannot overcome fundamental weaknesses inherent in any human enterprise.

Police and prosecutors make mistakes or, in some cases, lie and hide or manipulate evidence. Witnesses make mistakes or lie. What is billed as solid science turns out not to be. Remember bite mark evidence? And the science itself is too easily manipulated by the person doing the testing and analysis.

Yet we rely in this system to determine who will live or die.

Perhaps the most unjust aspect of capital punishment is the arbitrary way it is imposed. It disproportionately falls on the poor and people of color. The vast majority of murder prosecutions are under state laws, and the decision of whether to seek a death penalty often comes down to the outlook of the district attorney.

Here in Los Angeles County, recently elected Dist. Atty. George Gascón decided as a matter of policy, not law, to drop capital charges against defendants who had faced them under his predecessor. So the same crimes viewed by two prosecutors resulted in different decisions on whether they qualified for the death penalty.

The country is sliding in more ways than one.

Similarly, Barr himself revealed the arbitrariness of his decisions on who goes to the death chamber.

In announcing the resumption of executions, the Justice Department noted that the first five people to be put to death had victimized “the most vulnerable in our society — children and the elderly.”

So the attorney general of the United States decided that characteristics of the victims would determine the order in which he would issue death warrants. Characteristics, it must be noted, that would be sure to resonate emotionally with the public in a cynical effort to curry public support for resuming executions, and to shore up Trump’s bona fides as tough on crime.

In its 1977 decision in Gardner vs. Florida, the court reaffirmed an earlier finding that “death is a different kind of punishment from any other which may be imposed in this country,” and wrote that “it is of vital importance to the defendant and to the community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and appear to be, based on reason, rather than caprice or emotion.”

Or, one presumes, on a desire to manipulate public opinion during a political campaign.

That’s not justice under any definition of the concept.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.