Editorial: Congress needs to take back its power to declare war

- Share via

Last week the House Foreign Affairs Committee held a public hearing on “Reclaiming Congressional War Powers.” It’s an admirable aspiration, but more than talk will be necessary for the legislative branch to wrest back from the White House its constitutional authority to decide when the United States goes to war.

Presidents of both parties have deployed U.S. forces on the basis of outdated congressional authorizations or under an exaggerated notion of their powers as commander-in-chief. That lack of accountability harms more than Congress’ pride. It allows a president to put American troops in harm’s way — and potentially commit them to years of deployment — without having to persuade the people’s representatives that the mission is necessary.

Sometimes the mission is justified. That was true of President Obama’s reluctant decision to wage war on Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. To his credit, Obama requested a specific approval by Congress for that effort, but undermined the urgency of his own request by insisting that he could act on the basis of Authorizations for Use of Military Force approved by Congress decades earlier to address different circumstances. The Trump administration made similar arguments.

With the arrival of a new administration, there are signs that things may change. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told Politico that the president wants to “ensure that the authorizations for the use of military force currently on the books are replaced with a narrow and specific framework that will ensure we can protect Americans from terrorist threats while ending the forever wars.”

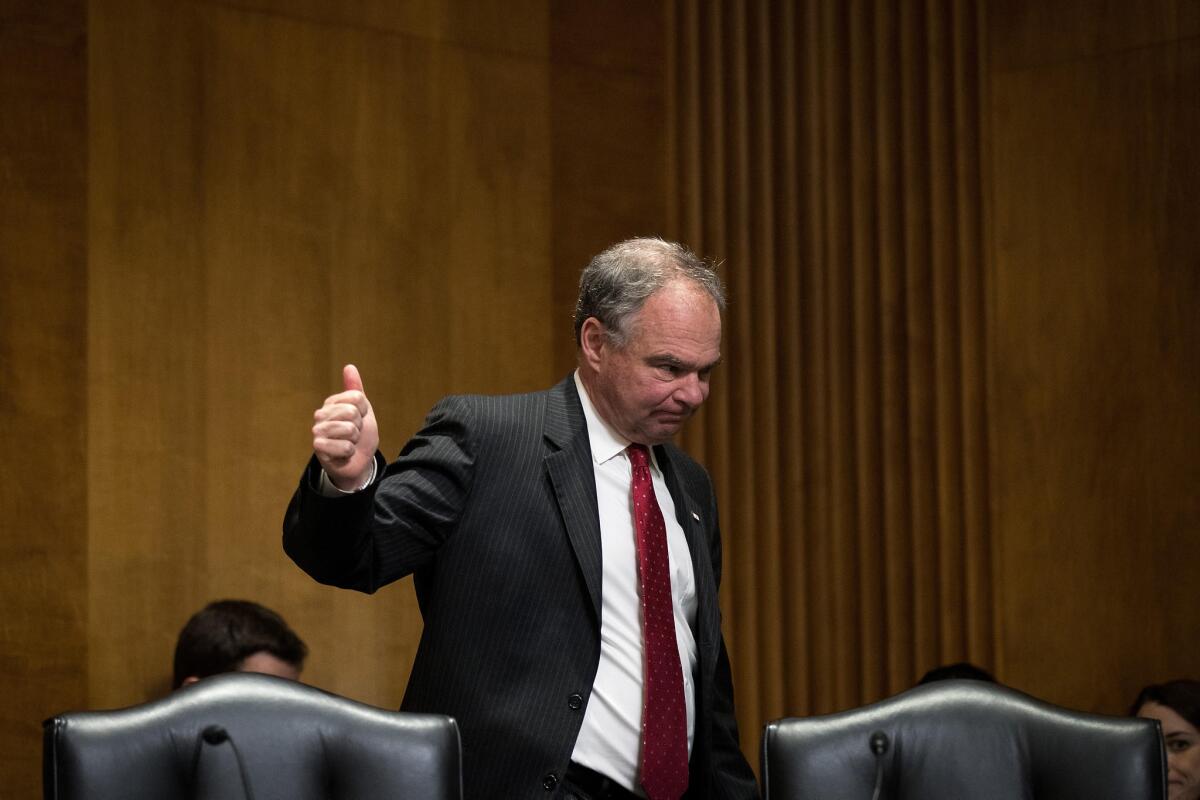

Meanwhile, Sens. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Todd Young (R-Ind.) have reintroduced legislation to repeal the 2002 AUMF, passed in response to a request by President George W. Bush before he invaded Iraq in 2003, and a 1991 resolution that authorized the Gulf War, which ejected Iraq from Kuwait. (The House voted to repeal the 2002 resolution last year.)

Kaine’s office said that he also supports replacing the 2001 AUMF, whose initial purpose was to retaliate for the 9/11 attacks, with a narrowly tailored resolution that would allow the president to respond to terrorist threats from groups such as Islamic State and Al Qaeda while preventing him from “engaging in unchecked war against virtually any group anywhere in the world.”

That’s easier said than done, as the history of the 2001 AUMF demonstrates. That resolution, which preceded the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, authorized the president to use force against “those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on Sept. 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons.”

But Congress later accepted the executive branch’s determination that the AUMF applied not only to Al Qaeda and the Taliban but also to “associated forces,” including Islamic State, an offshoot of Al Qaeda in Iraq, and groups in Somalia and Niger.

A replacement for the 2001 AUMF must be specific enough to prevent presidents from using it as a blank check to deploy U.S. forces against any and all terrorist groups without congressional approval. It also must be time-limited, to allow Congress to check a president who has abused his authority.

Important as it is to repeal and replace the current AUMFs, those resolutions aren’t the only means presidents use to assert their right to deploy troops. When Biden authorized an airstrike against Iranian-backed militants in Syria, the White House justified it as an exercise of the president’s commander-in-chief powers under Article II of the Constitution as well as the right to self-defense included in the United Nations charter.

The president does need to be able on short notice to defend American citizens and U.S. forces already deployed, but it’s too easy for a president to justify military action as what Bob Bauer, a White House counsel in the Obama administration, called “anticipatory self-defense.” At last week’s hearing, Bauer urged Congress to press the executive branch to withdraw Justice Department opinions that define self-defense in such an elastic way.

Congress also must strengthen the 1973 War Powers Resolution, which attempted to constrain the president’s ability to “introduce United States armed forces into hostilities” but is widely regarded as a failure. One obvious reform is to make it clear that “hostilities” include drone strikes. Another would be to toughen the requirement that the president consult with Congress “in every possible instance” before introducing U.S. forces into hostilities or imminent hostilities. Advance consultation should be mandatory.

Reasserting Congress’ role in the use of military forces doesn’t mean creating “535 commanders in chief” as the late Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) once warned. It does mean that the one commander in chief, the president, must not wage war on his own.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.