Column: What the union defeat at Amazon’s Bessemer warehouse means for the future of labor in America

- Share via

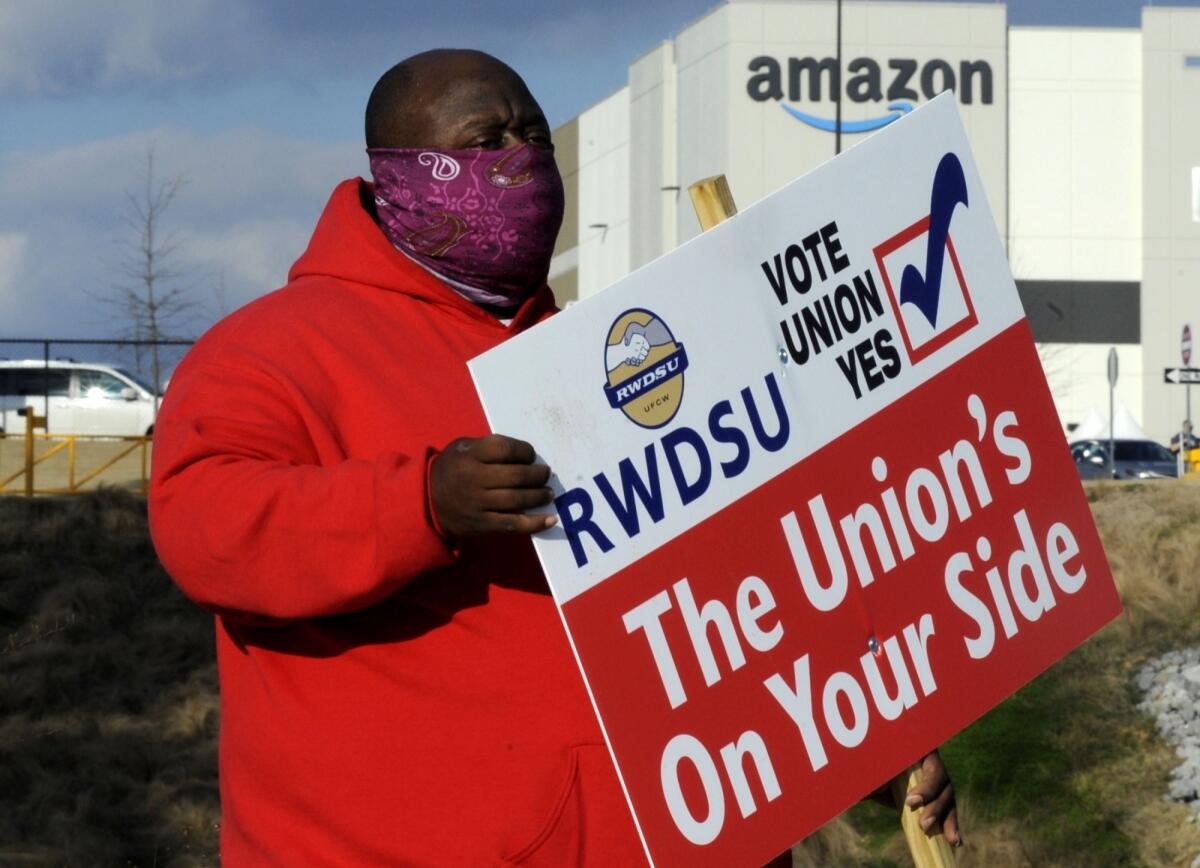

And just like that, the effort to organize nearly 6,000 workers at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Ala., was defeated.

The announcement Friday morning came as a grave disappointment to those who had hoped that a triumph over one of the world’s most powerful companies could lead to a string of further successes among Amazon workers elsewhere. The company now has 1.3 million employees.

Worse yet, it was a blow to the still-bigger prize that some had believed almost within grasp — a domino-effect reinvigoration of the labor movement all across the country. Labor’s more optimistic supporters had suggested that a victory in Alabama could herald a “sea change” that would reverse the long, slow decline of unionization. “If you succeed here,” said a hopeful Sen. Bernie Sanders in a visit to Alabama last month, “it will spread all over the country.”

Now, however, those dreams are on hold, at least for the moment. Instead of kicking off a reversal, revival or sea change, the workers at Amazon’s Bessemer fulfillment center voted overwhelmingly against representation by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. Union leaders suggested that they would challenge the results by charging the company with unfair labor practices; it’s unclear how strong their chances are.

It’s a depressing outcome. I’m not a steadfast, solidarity-forever kind of union guy. I don’t reflexively take labor’s side in all disputes; not all demands are reasonable, after all. And the workers of Bessemer have the right to make their own decisions about whether being represented by a union is in their best interest.

But American workers around the country need and deserve a strong union movement protecting them at a moment of historic income inequality and economic fragility. And at the moment, they don’t have one.

The decline of labor has been steep and damaging over the last five or six decades. More than a third of American workers were union members in the mid-1950s, but only 6% are in private sector unions now. In total, 10% of American workers are currently unionized if you include both the public and private sectors.

That decline may be good news for corporate profits and CEO salaries, but I believe it’s been bad for working conditions, for retirement security, for worker benefits and for the building of a stable, secure middle class. If we had stronger unions, would we live in society where less than half of the population gets its health insurance through an employer plan? Would income inequality be so high?

Is it a coincidence that in the heyday of the labor movement, so many private sector American workers had defined-benefit pension plans to retire on — but that today, such plans have all but vanished?

What accounts for labor’s decline? Lots of things, including globalization and the flight of American manufacturing jobs overseas. Adverse court rulings from union-hostile judges. The repeated thwarting of pro-union legislation in Congress. Plus, with so many jobs having been automated, workers have become increasingly expendable.

Over time, according to Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of history at UC Santa Barbara who has written extensively about labor, it has grown easier and easier for businesses to fend off unionization — by firing union organizers (which is illegal, but the penalties are weak) or by dragging employees in one by one to discourage them from supporting a union drive (which is legal). In too many ways, the playing field is tilted toward employers like Amazon, which control much of the flow of information to workers, can keep union organizers off company property and have the ability to spread messages of fear and uncertainty among employees who are worried about keeping their jobs.

In Bessemer, Amazon ordered employees to attend anti-union meetings on company time, among other tactics. It even posted fliers inside bathroom stalls.

The Amazon defeat is a disappointment, but the war is not over. This is an old American story that goes on and on. A particularly hopeful sign is the election of Joe Biden, one of the most pro-union presidents ever. His statement last month calling for “no intimidation, no coercion, no threats” against the workers organizing in Alabama was a powerful one for an American president. “Every worker should have a free and fair choice to join a union,” he said. “The law guarantees that choice.”

In other good news, popular support for unions is the highest it has been in years, says Harold Meyerson, an editor at large at American Prospect magazine who writes often about labor. According to Gallup, 65% of Americans currently approve of unions.

Supporters of labor are eagerly hoping for passage of the PRO (Protecting the Right to Organize) Act, a bill in Congress that would strengthen federal protections for workers seeking to unionize. It has passed the House and awaits action in the Senate. Democratic administrations have tried repeatedly for half a century to pass laws to strengthen unions with no success, mostly thanks to the filibuster in the Senate. This time, obstacles remain great, but with all the talk of abolishing or weakening the filibuster, supporters say, the bill shouldn’t be counted out.

As for the Amazon defeat — it was a bitterly fought contest in a region of the country that has been traditionally difficult for labor. It was a facility where workers’ starting pay is $15.30 an hour, substantially higher than the federal minimum wage. Bessemer would have been Amazon’s first unionized warehouse. The efforts to unionize the company will undoubtedly continue.

“When I first heard 20 years ago about Amazon building distribution centers all over the country, I thought, this is blue-collar work like we’ve had since the 19th century, with conveyor belts and assembly lines — it’s a prime target for unionization,” said Lichtenstein, the UC Santa Barbara historian. “But just because you have the technology of 1930s auto plants doesn’t mean you have the unions of auto plants.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.