Editorial: Are cash handouts a better antidote to poverty? Let’s find out

- Share via

Since President Johnson launched his War on Poverty in 1964, the percentage of Americans living in grinding poverty has plummeted. Despite a steady infusion of new programs, though, most of the gains in that fight came in the first decade. And while federal and state safety net programs have lifted millions of people out of poverty, roughly 1 in 10 Americans remain stuck at the bottom. In high-cost Los Angeles, more than 1 in 5 live in functional poverty.

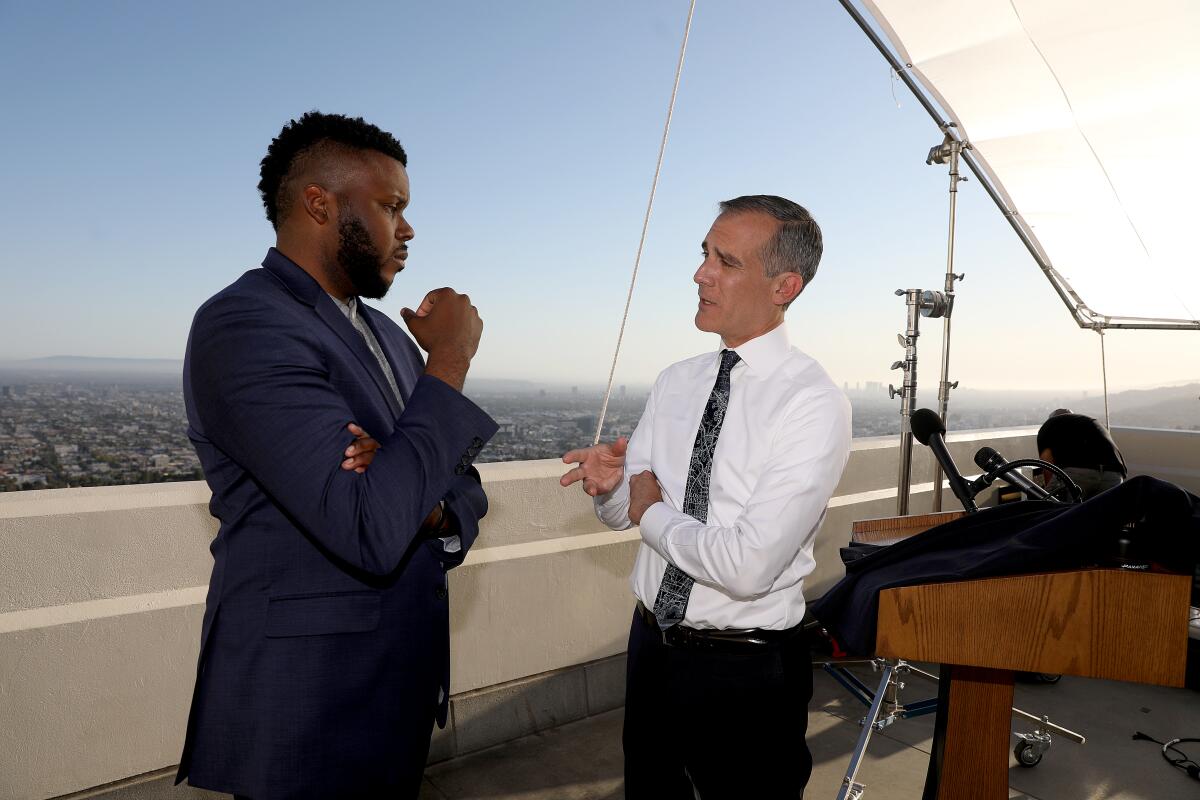

Recently, local governments have started to explore a new, simpler approach to poverty: giving low-income residents cash and trusting them to use it wisely. Buoyed by a windfall of federal COVID relief dollars, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti has proposed the country’s largest experiment yet, giving 2,000 L.A. families cash grants of $1,000 a month for one year. City Councilman Curren Price is planning a similar effort in his South L.A. district, giving 500 single-parent households $1,000 a month, and several other council members are pursuing their own guaranteed-income trials.

Although the pandemic has spurred interest in these programs, governments around the world have been flirting with them for a long time. And as a result, researchers have already rebutted some of the biggest objections raised, such as the notion that cash breeds indolence.

Nevertheless, there are other fundamental issues about how large the payments should be, who pays and receives them and how their effectiveness is measured that need to be addressed in these trials. And just as important, much of the American public remains skeptical of, if not outright hostile to, cash handouts for the poor with no strings attached. So it’s crucial that the city gather the data needed to measure not just the programs’ value to the recipients, but also to the people who are paying for them.

Unlike similar experiments in Stockton and Compton, Los Angeles’ trials will be funded with tax dollars, raising the question of why the city should use its strained budget to cover a social welfare cost typically left to counties and the state. That’s an important issue, but we think the city’s role is appropriate at this moment and urge it to proceed. The amount proposed is a tiny fraction of the $1.3 billion the federal government is providing L.A. in COVID-19 relief, and the cash grants will spur economic activity as the city climbs out of the pandemic-induced recession.

Decades of research on various versions of guaranteed income programs has shown that poor people use the money rationally and responsibly, in part because their needs are so great. Besides, they know far better than the government what their challenges and priorities are. So, too, have researchers found that cash grants don’t deter people from working, although some folks may put in fewer hours — which isn’t in itself a bad thing. The cash cushion can give people the chance to devote more time to improving their job skills or caring for ailing family members.

We’re also finding that the reliability of the cash grants provides benefits that are hard to quantify, but translate into more opportunity for poor families to make longer-range plans.

What we don’t know about these programs is what amount of cash produces the most bang for the buck, which people benefit the most from the grants (for example, are they more useful for single parents than childless adults?), and when and how to deliver the cash for maximum effect.

More fundamentally, we’re still trying to figure out how to define success for and measure the effectiveness of guaranteed income. It’s obvious that impoverished people are better off with more money. But can these programs deliver more than just temporary relief and lift people permanently out of poverty? Can they save society money on other fronts — for example, by reducing homelessness, crime or drug addiction? Can they replace other pieces of the safety net? Are they more cost-effective than providing a guaranteed job, free housing or some other intervention? Are they sustainable?

Garcetti’s test, which is being designed with the help of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Guaranteed Income Research, aims to fill in some of the knowledge gaps, alongside other efforts across the country. That’s a smart approach. Still, the experiments in the U.S. haven’t been done on a large enough scale and for enough years to answer the biggest questions about the ability of guaranteed income programs to pull people out of poverty permanently.

We’ve made huge strides against poverty in this country over the past 60 years, but progress has stalled. And entrenched, intergenerational poverty is at the root of many of Los Angeles’ problems. The pandemic has unexpectedly given the city the resources to try out a new solution. But it needs to show that guaranteed income is both sustainable and cost effective if it’s going to be more than a one-year experiment.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.