Editorial: America’s lack of universal broadband is an outrage

- Share via

When it unveiled its National Broadband Plan in 2010, the Federal Communications Commission declared that every American should have access to affordable and robust broadband service by 2020, along with “the means and skills to subscribe.” It was the right goal; as the COVID-19 pandemic has made painfully obvious, broadband is key not just to economic growth and productivity, but also to equal access to education, jobs, healthcare and an array of opportunities.

Eleven years later, however, as many as 42 million Americans, most of them in rural or remote areas, have no broadband available. Roughly three times that number can’t afford to hook into the lines running down their streets. Microsoft studied internet connection data last year and concluded that nearly half of the country wasn’t connecting at broadband speed. That has to change.

There’s been progress over the last decade, certainly. Cable and phone companies have invested significantly in their networks, increasing average connection speeds dramatically — for those who have them. Pushed by regulators, some of the bigger network operators are making low-cost versions of broadband available to low-income households. To its credit, Comcast has continued its deeply discounted “Internet Essentials” service long after it was required to do so, and it has doubled the download speed.

Yet the gaps remain, even in as tech-friendly a state as California. A recent survey by USC and the California Emerging Technology Fund found that about 1 out of 7 households in the state was not online or was connecting only through a smartphone.

A fundamental problem is the huge fixed costs of building and maintaining broadband networks, which make them uneconomic in areas with sparse population or low demand. The government has helped finance construction, but the results have often been networks that haven’t kept up with ever-growing demand. The FCC’s most recent effort, in December, awarded $9.2 billion over 10 years for rural broadband services, although some observers doubt that the providers that won the subsidies will deliver on their promises.

Nevertheless, far more public dollars will have to be spent if we’re going to give every American an equal shot at the services and opportunities that the internet provides. And there’s bipartisan support for a huge investment in broadband — President Biden proposed $100 billion in his original infrastructure plan, a group of congressional Democrats has a $94-billion proposal, and four Senate Republicans have suggested $65 billion.

To get a better return on the taxpayers’ investment, though, there need to be strings attached to the dollars. If the taxpayers are going to help build a network, it’s reasonable to demand more proof that the builder is qualified, can keep up with ever-increasing demand for bandwidth and can hold down the price for customers, or at least offer discounts for low-income households.

Moreover, networks have to be able to support multiple people per household simultaneously taking online classes, participating in video conferencing and connecting to servers — as families with good broadband connections have been doing for the last year. Not having or not being able to afford access holds back not just individual families, but the country as a whole. It’s an equal rights issue and an economic imperative.

High prices are the No. 1 reason cited by those who don’t sign up for broadband service. Congress offered a temporary fix in the last COVID-19 relief bill, putting up $3.2 billion for a $50- to $75-a-month subsidy for Americans with very low incomes or who lost jobs during the pandemic. But once the money runs out, broadband providers will still face little or no real competition, and no pressure to lower their prices.

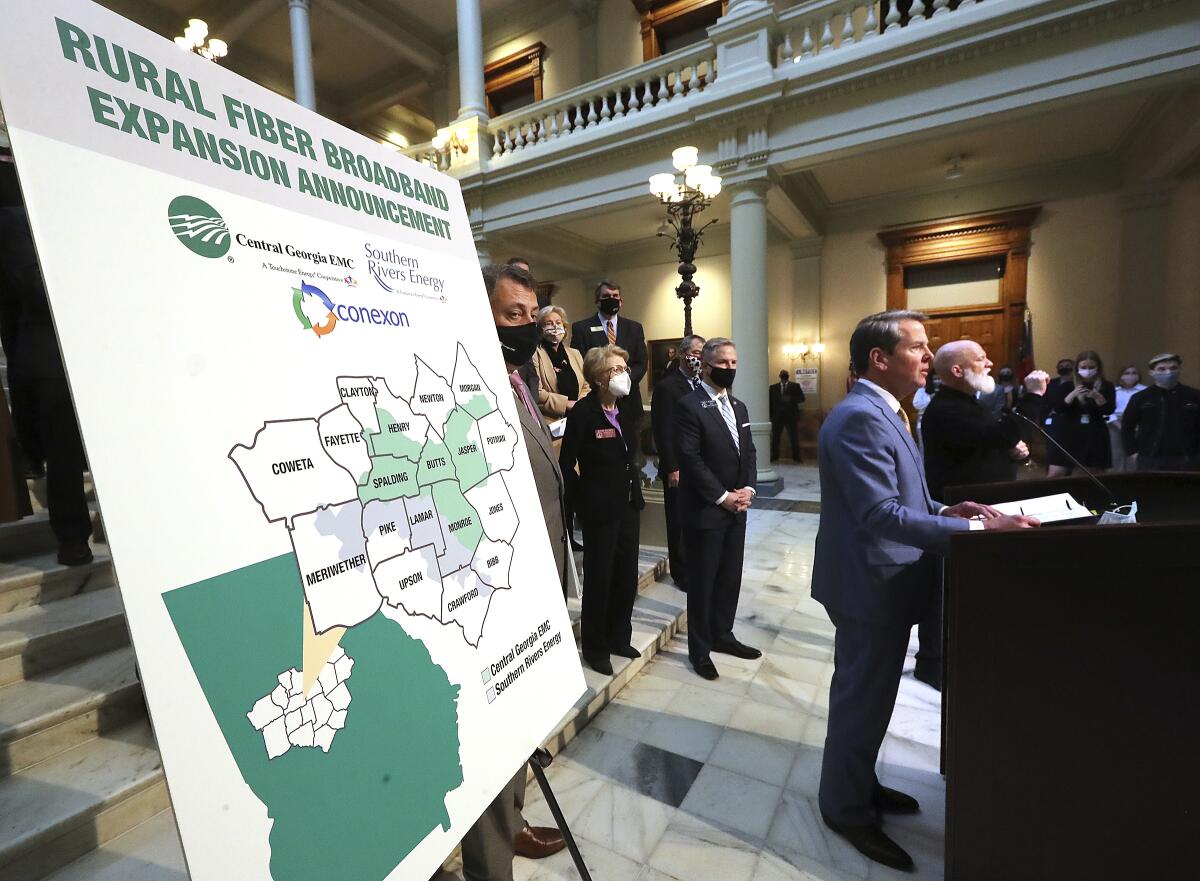

That’s why it makes sense for the government to promote competition through alternatives to local cable and phone monopolies. The FCC recently gave schools and libraries the authority to use $7.2 billion in federal grants to offer broadband service beyond their parking lots. But those institutions should also be allowed to create their own networks, rather than working through existing service providers. Other companies with their own networks, such as electric utilities, should be encouraged to leverage their resources to provide broadband to the public.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has called for using $7 billion in federal COVID relief to improve broadband services here, including a state-financed “middle mile” network that any internet providers could use to connect their local customers to major internet hubs. It’s a good idea that several other states have used to enable more companies to offer broadband service, both in underserved areas and in competition with existing providers.

And regulators should think creatively about the subsidies now provided for “lifeline” phone service. A worthy proposal comes from the Lewis Latimer Plan commissioned by the National Urban League, which suggests pairing broadband subsidies with unemployment benefits, Medicaid and other government programs to reach populations with an acute need for online services.

It’s long past time for us to stop trusting current subsidy mechanisms and existing broadband providers to solve the twin problems of access and affordability — they don’t have the right incentives or, in many cases, the right economics. As elected officials prepare for a massive investment in broadband, they need to look for new ways to get long-term solutions with a better return. The goal is the same today as it was 11 years ago, but as the pandemic showed, the need is considerably more acute.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.