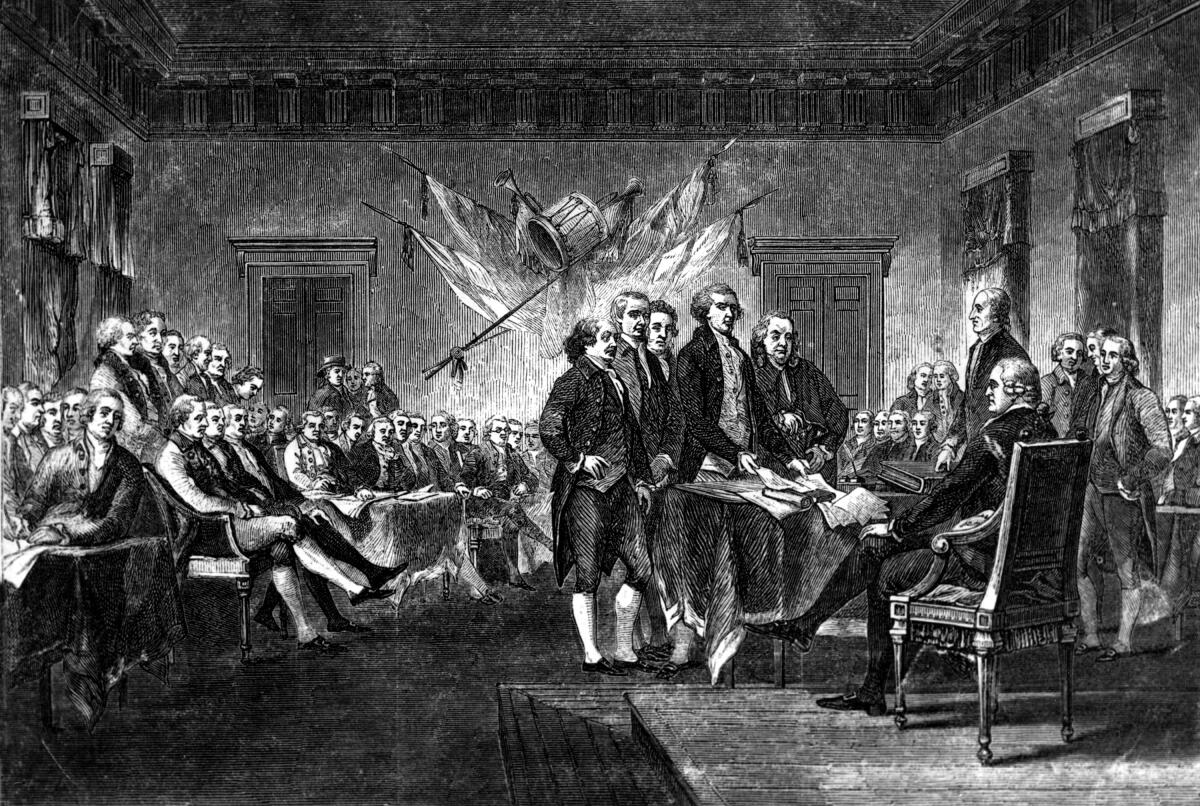

Op-Ed: Lessons from the American revolutionary generation for today’s pandemic generation

- Share via

Lucy Mack was born in New Hampshire in July 1776, just four days after the United States proclaimed its independence. But when Lucy looked back on her childhood, she didn’t remember a triumphant new nation. She recalled the war for independence above all as a time of hardship, during which her family had endured sickness and scarcity. These trials, more than the ideals embodied in the Declaration of Independence, had shaped her and the other members of the revolutionary generation.

Americans who are young this Fourth of July have also witnessed the world turn itself upside down. The political upheavals of recent years, capped by the COVID-19 pandemic, have wrought disruption and destruction on a rare scale. The experience of the American revolutionary generation offers lessons about how this kind of crisis can lead to lasting social transformation: by giving young people a vocation for change that they carry with them into adulthood.

There are surprising parallels between the situations of 1776 and 2021.

Like the interwoven health and political crises of the last four years, the American Revolution exploded in a society that was stagnant, self-satisfied and unjust. During the decade before 1776, British North America’s businesses boomed while inequality grew. Insular, oligarchical elites ruled over most of the colonies. White Americans wrapped themselves in the trappings of British patriotism. The system stood on the backs of enslaved Black Americans — a legacy that still haunts the United States.

The revolutionary war temporarily cracked open this calcified social and political order. Some of the powerful were toppled, from Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Hutchinson to members of the wealthy and powerful New York De Lancey clan. Warfare flung thousands of ordinary people into new roles as soldiers, refugees and settlers. A severe economic downturn after 1783 prolonged the instability well after the war’s end.

Black Americans experienced these disruptions with extra force. Political and social disorder could give enslavers greater power over their bondmen. But war also offered chances for freedom. Richard Allen, born to an enslaved mother in Delaware, purchased his freedom in 1780, at the age of 20, and joined the growing Black community in Philadelphia. Thousands of other enslaved people fled from slavery during the war. Many saw the violence of war firsthand. Gabriel, born into slavery in 1776, probably remembered the British soldiers who had razed Richmond, just six miles from his home, in 1781.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the hierarchical old order reasserted itself with a vengeance. Struggles for economic justice, and for the rights of Black Americans and women, were rebuffed by a reinvigorated elite.

But the war’s effect on the revolutionary generation’s social imagination could not be undone. Having seen firsthand how the social and political order could be upended, many became champions of change.

As the revolutionary generation came of age around 1800, a quarter-century after the Declaration of Independence, they put their vision into practice. Political equality for white men, which had been largely limited to property owners, expanded quickly as the new generation took charge. By the early 1820s, the United States had near-universal white male suffrage.

The struggle against slavery and racial inequality gained in both creativity and urgency as the revolutionary generation took the reins. Richard Allen became a leader of Philadelphia’s Black community. He was the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination, and among the originators of the Colored Conventions movement, which both became powerful national forces pushing to end slavery and achieve civic equality for Black Americans.

Gabriel, who had become a skilled and literate craftsman by the 1790s, sought an end to slavery by more direct means. In 1800, he helped organize the largest rebellion of the enslaved in North America to date, one that relied on a web of secret Black information networks that had grown up over the previous decades. Though the rebellion failed and the 24-year-old Gabriel was put to death by vengeful planters, it marked the start of a building wave of overt Black resistance to the institution of slavery.

Nor was the generation’s desire for change limited to politics. Lucy Mack’s early life had made her a spiritual seeker, like many of her contemporaries. After 1800, she experimented with various denominations and religious practices. She eventually became one of the earliest adherents to the new Christian faith created by her son, Joseph Smith, in the late 1820s. His church, the Latter Day Saints, was among the most innovative religious movements of the 19th century.

For those of us wondering how we can hope to heal our fractured society, looking back to the generation that came of age in the revolutionary era offers some grounds for optimism. The United States in 2021 remains marred by racial inequality and democratic disfunction. But today’s young Americans, like the young men and women of 1776, have lived through a unique moment of rapid change. If we are lucky, this experience will give them a vocation, like that of the revolutionary generation, to bring about social and political transformations that the adults of today can hardly imagine.

Nathan Perl-Rosenthal is an associate professor of history at USC. He is currently completing a book titled “Generation Revolution: Political Lives in a Revolutionary Age, 1760-1825.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.