Column: The never-ending obfuscation of war

- Share via

Russia ratcheted up its battle against truth and transparency by several notches when it passed a law earlier this month banning the words “war” and “invasion” to describe its behavior in Ukraine. The law sets prison sentences of up to 15 years for people who dare utter those words or spread other “fake news” about the conflict.

It’s a throwback to the country’s ugly totalitarian past and suggests Russian President Vladimir Putin is scared of his own people and worried about his grip on power.

But let’s keep things in context. Although the United States and other democracies don’t generally prosecute their citizens for speaking out candidly and honestly, there’s nothing new about governments trying to control the language of war. In fact, the packaging and marketing of war through obfuscation, euphemism and even dishonesty is almost as old as war itself.

Opinion Columnist

Nicholas Goldberg

Nicholas Goldberg served 11 years as editor of the editorial page and is a former editor of the Op-Ed page and Sunday Opinion section.

It is ludicrous that Russia insists its brutal behavior in Ukraine, which has already killed thousands of civilians and soldiers, is not a war or an invasion but merely a “special military operation,” whatever that means. Yet for years the United States maintained that the Korean War was not a war. President Truman referred to it as a “police action” and Congress said it was merely a “conflict.” More than 2.5 million people died, including more than 30,000 American military personnel.

Governments don’t like to acknowledge starting wars because wars, for obvious reasons, are not very popular. In 1949, in fact, the former U.S. Department of War was renamed the Department of Defense, even though most Americans knew, if they bothered to think about it, that the department’s work did not just involve defense.

I’m not suggesting a moral equivalence between what the Russians are doing when they toss people in prison for telling the truth and what democracies do when they use misleading language. But the underlying objectives are similar.

Every Madison Avenue ad executive knows that when you name something, you set the terms of debate. If it’s something as unpopular as war, it may serve your purposes to cloak it in jargon or acronyms, call it the opposite of what it is or make it sound clinical and less disturbing.

Call civilian deaths “collateral damage.” Don’t call a coup a coup; call it “regime change.” Rebrand the war department.

In trying to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Putin is engaging in “hard propaganda,” which is meant to convey the speaker’s power, not persuade.

This sort of misnaming goes back at least as far as the Romans, who expanded their empire through a process they called “pacification.” (Much as the Russian newscasts last week called the Ukraine invasion “an operation to restore peace.”)

The Nazis referred to the murder of Jews in gas chambers as “special treatment.”

According to the late Berkeley linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, it was during the Crimean War in the mid-19th century that the more bloodless word “casualty” began to be used to refer to the maimed and dead.

The objective in each case was to sanitize or justify a gory and unpleasant business.

“Different linguistic frames can bias peoples’ moral judgments,” wrote a group of Canadian researchers last year, in one of many studies of the subject. They noted that substituting different verbs, adding more agreeable phrases, using euphemisms and adopting the passive voice can make morally offensive behaviors more palatable to people.

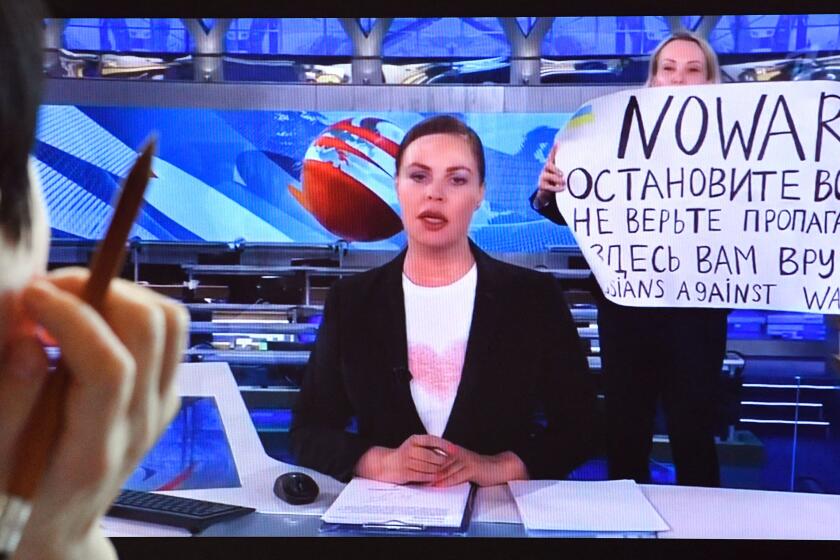

A journalist who held up an antiwar sign behind the anchorwoman of one of Russia’s most-watched news shows was released after her arrest.

A week into the war in Ukraine, nearly 6 in 10 Russians supported it and only 23% opposed it, according to one independent poll. That’s because propaganda and doublespeak, combined with near-total control of the media, are effective tools for winning hearts and minds.

We call this misuse of the language Orwellian because it was George Orwell, the British journalist, critic and novelist, who wrote so clearly about it in “1984” and elsewhere.

“Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification,” he wrote in his classic 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language. “... Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

During the George W. Bush administration, two egregious euphemisms stand out. The first is “extraordinary rendition” to refer to snatching terrorism suspects off the streets of foreign cities and sending them to so-called black sites in foreign countries. The second is the phrase “enhanced interrogation techniques” to refer to torture. (Andrew Sullivan argued in the Atlantic in 2007 that the latter phrase had roots in the Gestapo interrogation method known as “Verschärfte Vernehmung,” which translates roughly as “sharpened questioning” or “intensified interrogation.”)

And to one degree or another, news organizations followed the government’s lead: The Times used the phrase “enhanced interrogation” for a while, although usually in quotes with an accompanying phrase such as “which some people consider torture.” Some other newspapers adopted the administration’s language or used their own euphemisms, referring to waterboarding, sleep deprivation and slamming suspects against walls as “severe tactics” or “rough treatment.”

The Times’ Marcus Yam, no stranger to war photography, gives a first-person account from Ukraine.

So far, President Biden seems to be more straightforward than many of his predecessors, despite his use of at least one hackneyed, misleading Cold War-era anachronism: “the free world.” Then again, the U.S. didn’t start the war in Ukraine and is not directly engaged in the fighting, so he has less to obfuscate.

The problem with spinning and manipulating the language of war is that when you make harmful acts sound harmless it becomes that much more likely that they will continue.

If war is not hell but is sanitized, innocuous and bureaucratized, then why not engage in it more often? If my country is not an aggressor behaving brutally but is engaged in pacification or enhanced interrogation or in a “special military operation,” why shouldn’t I support it?

Honesty is rare when governments go to war. Journalists, scholars and citizens on all sides must listen hard to separate facts from spin if they hope to understand the realities and know when they’re being manipulated. Then they must call it to the attention of others — if they can do so without being imprisoned.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.