Editorial: L.A. Unified fails to get kids the tutoring they need

- Share via

Once again, Los Angeles Unified School District shows that it’s great at making ambitious academic plans but downright abysmal at keeping track of how those plans are being implemented and whether they are working.

Long before COVID-19 brought chronic absenteeism to crisis levels, the district launched an array of programs in 2016 to increase regular attendance. But by the end of the following year, attendance had not improved and the district assessed the effectiveness of only a couple of the several programs to see if they worked, and found mixed success.

“L.A. has the greatest plans in the world and probably the worst follow-through,” former L.A. Unified board member Richard Vladovic said at the time.

Some education factions insist that students didn’t suffer academically last year. This rosy view can only evade accountability and hurt kids.

That’s still the case now that the topic is tutoring, which is a cornerstone of L.A. Unified’s plan to make up for learning loss from the long months of Zoom school during the pandemic.

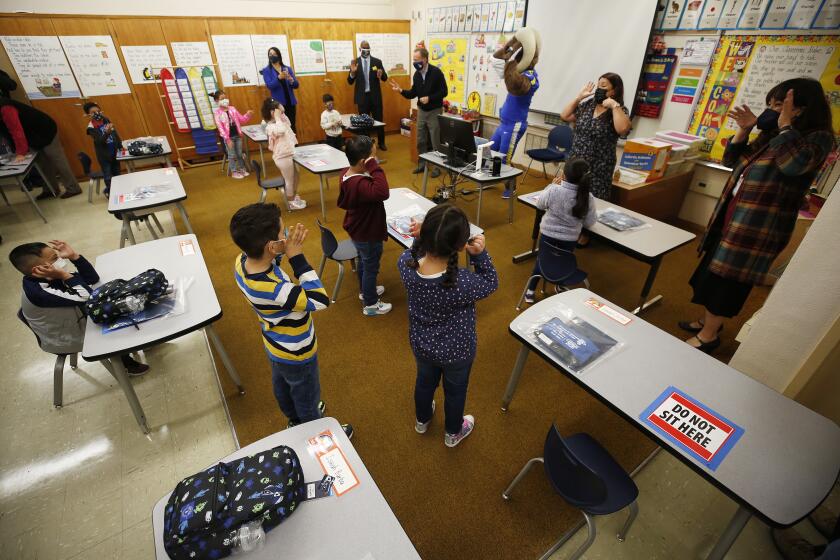

The district began several programs last spring and this academic year that schools could choose from to help struggling students. And there is evidence that one of them helps: Primary Promise, which provides daily extra reading and math instruction in small groups to children in the earliest grades. Research has found that kind of “high dosage” tutoring, conducted one-on-one or in small groups several times a week, is one of the most helpful interventions for students who are finding their lessons difficult to grasp.

But overall, the school board received deeply disappointing news last week about L.A. Unified’s tutoring efforts. Not even 10% of students have been receiving tutoring, and the numbers are especially dismal in middle and high schools, at 4% to 6%. The district doesn’t have a hard number of how many students need tutoring but it’s widely acknowledged that it’s probably much higher than 10%.

And the district can’t say how many students have received high-dosage tutoring outside of the Primary Promise program. Staff also reported to the board that they don’t know why the numbers are so low. Is there a lack of qualified tutors? Unknown. Is it that more students were receiving tutoring but their numbers hadn’t been reported to the district’s central office? Also unknown.

Students in Los Angeles, especially those of color, fell far behind during remote learning. Tutoring could help, but their mental health matters more.

It’s shameful that the district is unable to answer these simple questions. Once again, the district had grand plans, but little follow through. It’s a problem that apparently few students are being tutored — but a much bigger one that the district doesn’t know where the failure occurred or even which tutoring efforts have been effective.

Fixing this frustrating lack of oversight is going to be one of Superintendent Alberto M. Carvalho’s biggest challenges because it’s embedded in L.A. Unified’s culture. The clumsiness and disappointment of promising big things and then not making them happen in an effective and organized way — the iPads-for-all mess and the graduation requirement, later weakened, that students must receive a C in all college-prep courses come to mind — leads the district’s critics to bemoan the massiveness of L.A. Unified and call for breaking up the district.

The district also is unaccountably providing tutoring services in middle and high school mostly to students who ask for the extra help, or whose parents step in to seek it. But not all students realize they need a tutor or that one might be available. They might be embarrassed or too shy to ask for one. Parents might not intervene for their children because of past experience feeling that the school isn’t responsive or doesn’t understand the extent to which their children face major academic challenges. The schools should proactively seek out the students who need the most help and get it to them first.

If this were early November, the administration might be forgiven for not having the full picture. But the school year ends in two months. The students need help now; they can’t afford to wait another year to fill the academic gaps left by more than a year of remote learning. And the federal pandemic relief money provided to schools for this extra help is scheduled to dry up in 2024.

Part of the confusion over tutoring stems from the district’s efforts to decentralize authority and allow more decision-making by principals and staff at individual schools. Local decision-making has advantages, such as nimbleness and better knowledge of a particular neighborhood’s needs. But that does not absolve the central office of the responsibility for setting academic standards, monitoring whether its plans and programs are effective and stepping in when things are going wrong.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.