- Share via

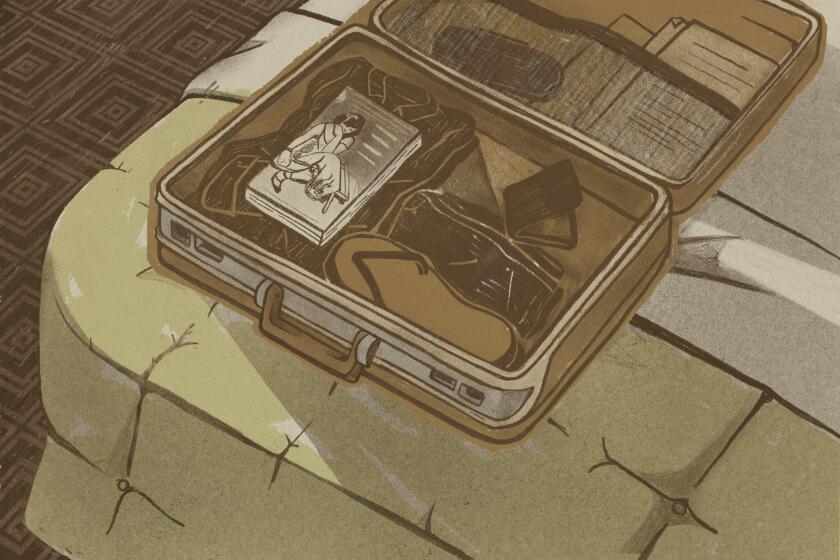

My most prized possession was once somebody’s trash.

It’s a blocky, black radio that was manufactured in 1941, the year my father was 12 years old. I snatched it from the county landfill when I was 13, in 1978.

The person who threw it away must have determined they couldn’t fix it, though it seemed they thought someone else might. They had set the radio off to the side of the dumpster, safe in plain view, just in case some industrious person with know-how appeared.

That person was my father, who ran an electronics repair business from our garage. Though at first reluctant to save “that ugly old thing,” he seemed pleased hours later when he entered the kitchen announcing that the radio worked fine and had only needed a tube. For years after this, my father kept that radio on a shelf above his workbench, listening to country singers croon about lonesome truckers.

We lost my mother-in-law on June 3. My bond with her was unexpected.

I like to think of myself as a minimalist, but since my father died in 1994, I’ve carried what I consider to be “our” radio thousands of miles from the Appalachian farm where I grew up, out to Los Angeles, and then many years later back home again. In California, I’d tune our radio to horse races being transmitted from Santa Anita or Hollywood Park while cleaning my kitchen. Or I listened to Paul Harvey, Casey Kasem or evangelists spouting “truths” about Jesus and cars.

I’ve become somewhat protective, even superstitious, when it comes to our radio, which now resides on a shelf above the space where I work. These days I use it sparingly; I realize that each time it flickers to life could be its last. How does one go about finding ancient tubes nowadays? Where are the parents with the know-how to fix such things anymore?

It was a Sunday when my father died. On the anniversary of that day each year I turn on our radio to make sure it still works, and also to see what’s going on in the AM spectrum, which seems a world all its own. My yearly visit has become more than a ritual to keep me connected to a man who agreed to adopt me when he and my mother couldn’t conceive — a man who never seemed to understand me or what he considered frivolities, my love of reading books and writing stories, my nostalgia for all things abandoned, neglected or lost.

Each time I listen to our radio, I see my father just as he was that day when we found it. I see his 40-something face and hear his amused, solemn voice as he decides to humor me and accept me just as I was. I see the gentle wind push his thinning hair across his even more gentle face as he watches me carry my great find to his truck, not knowing that I’m thinking, “What splendid luck!”

If I hadn’t gone to graduate school, I’d probably be the UPS driver my father, who valued stable employment, wanted me to be.

My father could fix anything, and he often did — like the final time he saved me from the side of a busy highway when the old Fiat he’d warned me not to buy broke down once again. My father’s lack of fear, along with his decision to carve out an authentic life on the land without caring how the rest of the world measured success — memories of these traits are among my greatest treasures. Each time I turn on our radio, I’m reminded of this. I’m also reminded that while some children might grow up playing sports or taking swanky vacations, my father and I built cattle fences and shared an old radio we found at the dump.

This year when I turned on our radio for the first time in a dozen months, I heard the booming voice of an evangelist sharing pretty much the same message I heard the last time I listened. He’s preaching about the various ways one might earn the Father’s eternal love and salvation when he interrupts his own sermon to announce a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to hurry down to the local Ford dealership to buy a new car.

I marvel that our radio is still going, its signal strong and clear. I marvel at how, each time I listen, my father and I grow ever closer as the ad man’s voice fades away.

Robert McGee lives in Asheville, N.C. He has written for the Sun magazine, the Christian Science Monitor and the forthcoming book “Chicken Soup for the Soul: Angels and the Miraculous.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.