Opinion: Trump’s mug shot is historic, but arrest images of ordinary people shouldn’t be published

- Share via

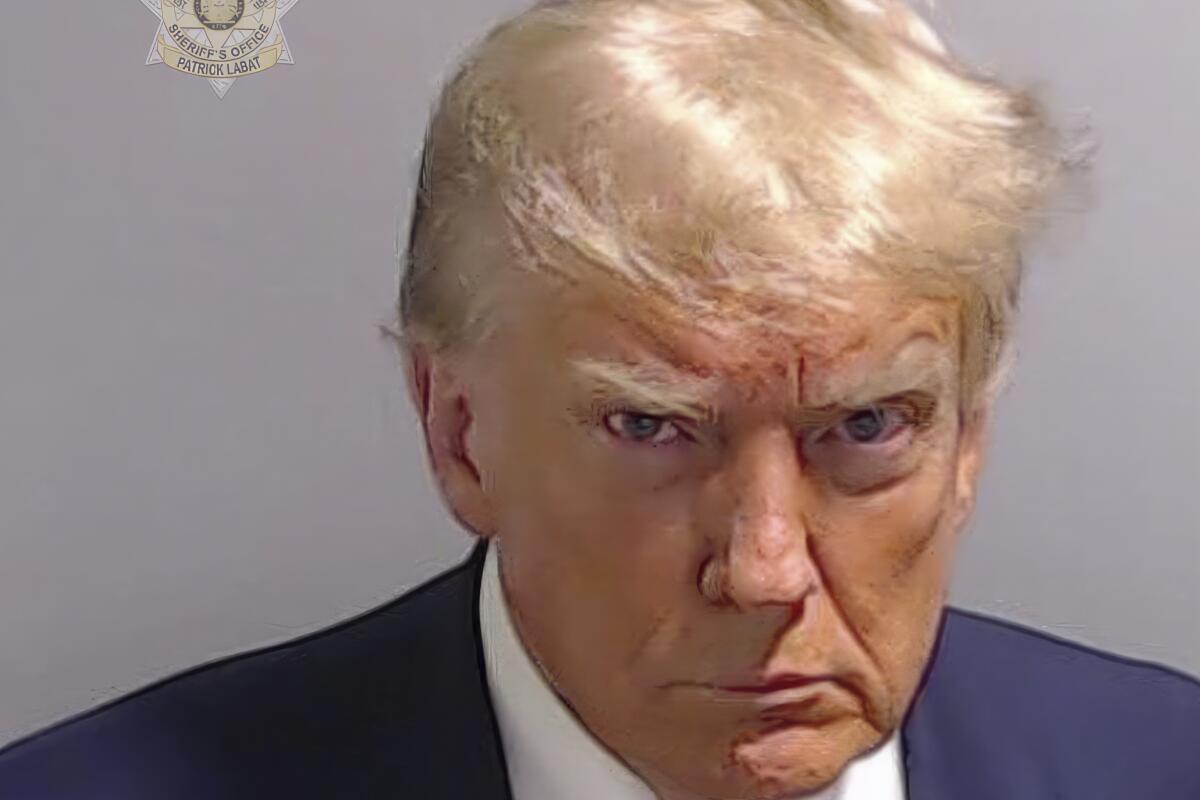

On Thursday, like every American journalist — and many Americans period — I waited all day for former President Trump’s mug shot.

Then my husband finally pointed to the TV and yelled, “Blue Steel!” (the Zoolander resemblance was uncanny). As Trump’s feral scowl graced every news platform, I watched an overwhelming and understandable catharsis saturate the nation’s top cable news networks, with commentators treating the mug shot as a victory or declaring it justice.

Now, I did experience some satisfaction as newsrooms plastered the former president’s mug across platforms while he faces an astonishing list of charges. However, I am also a harm reductionist who sees a once-in-two-centuries opportunity.

The former president reported to the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta for booking on charges related to his attempt to overturn the 2020 election result in Georgia.

At long last, the mug shot — the most journalistically fraught photo format — is having the moment we need to change a media convention that has always disproportionately harmed our country’s most vulnerable populations.

Trump, as an extremely powerful figure, may seem like an exception to the rule. But his picture is the ultimate case that pokes a hole in the logic that newsrooms use to defend publishing these photos. It’s time for newsrooms to abandon mug shots altogether, with very few exceptions.

For the last 15 years I’ve taught journalism at Temple University, and I run a community newsroom in Kensington, a North Philadelphia neighborhood with an intersection of our society’s most oppressed populations (it’s also the neighborhood that has been trotted out like a prop by GOP presidential hopeful Vivek Ramaswamy). I’ve seen over and over how easily these groups — including Black and brown communities, migrants, single parents, sex workers, the unhoused, veterans and others with high risk of trauma and limited economic opportunities — are criminalized. Mug shots feed that system.

Former President Trump chose to skip the first Republican primary debate in favor of an interview with Tucker Carlson, but it failed to overshadow the debate.

The supposed arguments in their favor concern public safety — that they alert the public of a potentially dangerous person, confirm an arrest and avoid confusion as to which individual (who might have the same name as others) was accused. But that’s not the effect they usually have in reality.

Kensington, while a stunningly resilient community, is overwhelmed by poverty and poor health outcomes, and it is engulfed by one of the country’s largest open-air drug markets. Here, many people’s life circumstances combine with their environment to push them into the drug market, selling, using or both. Unsurprisingly, many of them get arrested (particularly if they belong to groups that are over-incarcerated nationally such as Black Americans and people with mental health or substance use disorders). Their mug shots become fodder to splash across a page. But for what gain?

Mug shots publicize the identity of people who have not yet been convicted. Even when people are found guilty of the crime for which they were arrested, the public’s need for that visual information is so minuscule that the harm of publishing overwhelms it. It’s much less likely that a mug shot will, say, prevent an arrested individual with limited resources from fleeing their jurisdiction than that it will fuel local gossip: “Hey! The neighbor’s son got his second DUI!”

Even so, as researchers have noted, local news outlets rely on the criminal justice system’s steady flow of mug shots to increase advertising revenue with minimal production. This, despite the stigma mug shots create for people who, unlike Trump, aren’t public figures and are experiencing their worst moments. There’s also no evidence that these photographs deter crime.

While some news outlets and projects, my startup newsroom included, have taken a firm stance against mug shots, influential organizations remain resistant.

For example, the Associated Press, long considered the gold standard for journalistic style and ethics, has already published relatively strict guidelines on using artificial intelligence. Yet the AP’s mug shot ethical standards are weak, buried under their 2021 decision to stop publishing the names of individuals accused in “minor crime briefs.”

The only credible public safety argument to use a mug shot is when a person presents an active threat, such as someone on the run for a violent crime, and no other clear recent photo is available.

Trump’s mug shot does not fit that category — though it is undoubtedly the strongest case I’ve seen for newsrooms running a booking photo purely for public interest. But even this instance shows how thin the arguments for mug shots are.

In Trump’s case, there is certainly no other former president named Donald J. Trump, so there’s no need for a photograph to resolve that issue. While some may want a picture as proof that Trump was actually arrested, there are other ways to verify arrest.

Yes, I felt some schadenfreude seeing a mug shot of Trump, who has so often thrown baseless accusations of criminality toward my city and others. But is the satisfaction of a broken criminal justice system catching up to someone like Trump reason enough to engage in a practice that is overwhelmingly harmful?

It’s not. Trump’s mug shot may well be the definitive U.S. photo of 2023. But let’s hope that it helps advance a wider conversation about moving away from photos that label mostly ordinary people as criminals before they’ve even had the chance to go though the justice system.

Jillian Bauer-Reese is an associate professor of journalism at Temple University and the founder of Kensington Voice, a community hub and newsroom in North Philadelphia.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.