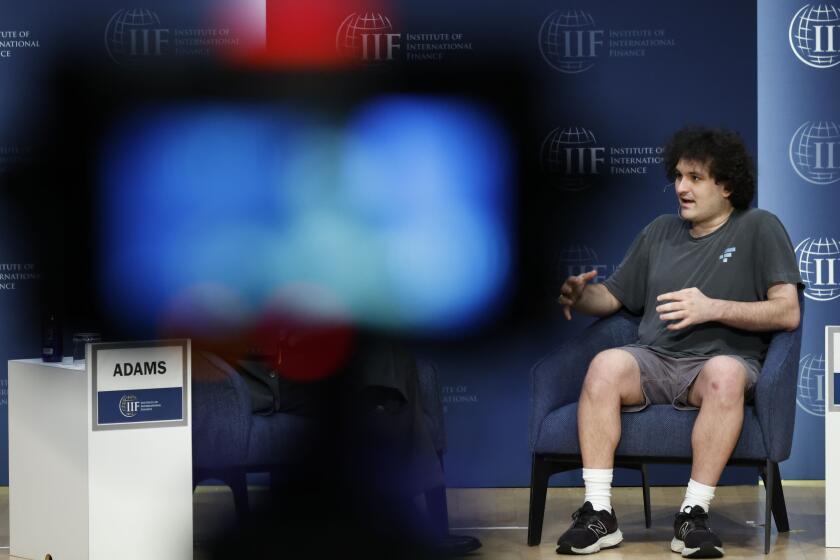

Opinion: Why Sam Bankman-Fried’s aversion to ‘grownups’ will likely prove to be criminal

- Share via

“Effective altruists” believe they should devote themselves to benefiting others the best they can. Some take this position to extremes by pursuing the highest-paying jobs they can find and then donating their riches to vetted charities that save the most lives per dollar deployed. One of the most famous effective altruists, Sam Bankman-Fried, is currently on trial for fraud.

In Michael Lewis’ new book, “Going Infinite,” Bankman-Fried is portrayed sympathetically as a brilliant, humane but emotionally crippled figure. Though he seems to lack the capacity to feel empathy for those around him, he reasons himself into the effective altruists’ utilitarian outlook. After earning a physics degree from MIT, Bankman-Fried joined the trading firm Jane Street, where he learned to arbitrage small price differences between assets. He proved to be quite good at quickly identifying, calculating and executing gambles.

Update:

5:36 p.m. Nov. 2, 2023Sam Bankman-Fried was convicted on Nov. 2 of all seven charges of fraud and conspiracy after a monthlong trial.

But as Bankman-Fried surely understood, Jane Street simply leached rents from the financial system, rather than doing anything to benefit humanity. So he left to find a better use for his talents.

The ridiculous story of Sam Bankman-Fried, FTX and cryptocurrency generally is aired in two new books, but only one is worth reading and it’s not by bestselling author Michael Lewis.

He soon noticed that price discrepancies were much greater in cryptocurrency markets, where poorly designed exchanges and the absence of regulation had kept professionals away. So, he founded the hedge fund Alameda Research, where he made millions of dollars by replicating Jane Street’s arbitrage strategies in more fertile hunting grounds.

Recognizing that the crypto market needed a better-designed exchange that professional traders would be willing to use, Bankman-Fried enlisted his friend Gary Wang to write the code for FTX. An exchange can be extremely profitable because it takes a cut of every trade without taking much risk. FTX innovated by closing out trades extremely rapidly to minimize the risk that a trader’s collateral was insufficient to cover losses, which would require FTX itself to spread that loss to other traders.

Because dozens of crypto exchanges already existed, Bankman-Fried needed to lure their customers to FTX and bring in as many crypto-trading novices as possible. So he spent hours pitching FTX on television, and donated large sums to political candidates — Democrats and Republicans alike — hoping that the government could be persuaded to license FTX’s business.

Michael Lewis’ latest book, ‘Going Infinite,’ on Sam Bankman-Fried and the rise and fall of FTX, is well-timed, unsatisfying and surprisingly confusing.

To support FTX, Alameda was enlisted as a market-maker, stepping in to buy or sell on the opposite side of the exchange when not enough traders materialized. But, of course, Alameda needed funds to take the losing sides of trades, and to hold onto the assets until they could be resold. Bankman-Fried allowed it to borrow an unlimited amount of money from FTX, effectively using customers’ funds to backstop those same customers’ trades. The risk-minimization technology was a mirage.

This may explain how FTX gained its competitive advantage over the other exchanges. FTX customers got good terms, never realizing that they were exposed to massive risk. When they finally learned the truth, they withdrew their money, and the house of cards collapsed.

The government alleges that Bankman-Fried, the majority owner of both firms, deliberately gambled with customer funds. Bankman-Fried claims that he did not know that Alameda owed $8 billion to FTX. He also contends that he was not making fraudulent statements when he or FTX offered various assurances that customer funds were protected, and that FTX was “fine” up to its collapse.

Prosecutors depict Sam Bankman-Fried as a calculated criminal who used investor deposits at crypto giant FTX as a personal bank account.

Lewis seems to believe him. But the law defines fraud to encompass reckless disregard of the truth. Bankman-Fried must have understood that he was taking extravagant risks by refusing to hire qualified financial and legal experts to oversee his business — risks that are well documented by Lewis.

Bankman-Fried’s aversion to “grownups” likely will turn out to be criminal in managing a $32-billion firm. Moreover, as Lewis shows, because Bankman-Fried was never very honest or straightforward with people, few employees were in a position to spot trouble, bring it to his attention or expect him to be responsive.

More to the point, there is reason to think that he knew what he was doing all along. Lewis recounts Bankman-Fried’s habit of calculating an “EV” — expected value — for all his actions, including things as trivial as keeping a promise to attend a meeting or speaking event. He would mentally assign a probability that a particular meeting would generate revenue for his firm or possibly value for society, multiply it by that value, then compare it to alternatives.

The 19th century British philosopher Henry Sidgwick might point to this case as an object lesson of the risks when fallible humans employ utilitarian thinking. But that is probably not how Bankman-Fried would see it, even now. The question is whether the collapse of his financial empire, and the damage inflicted on his employees, customers and investors was justified by the expected social payoff had FTX survived.

Serving a long prison sentence for fraud was itself a part of the downside risk that, discounted to present value, surely shrank to nothing relative to the potential payoff of saving humanity. FTX was a gamble. And Bankman-Fried was exceedingly confident of his ability to calculate the expected value of big gambles.

Eric Posner, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, is the author of “How Antitrust Failed Workers.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.