Opinion: Will we let mpox spread, repeating devastating public health failures?

- Share via

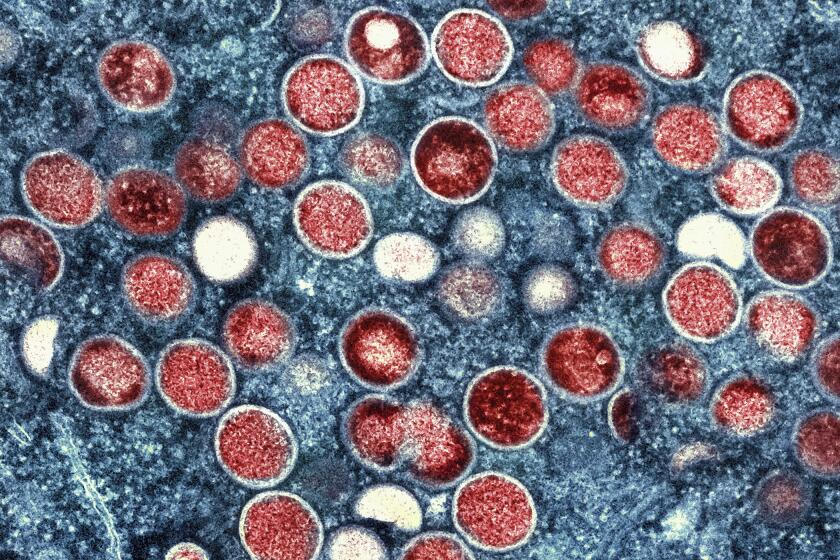

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is back in the news. As of early September, the World Health Organization has reported more than 5,000 laboratory-confirmed cases this year. Given the well-documented shortcomings of mpox surveillance, these numbers underestimate the true magnitude of the disease burden.

The highest number of cases are in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the current outbreak has expanded to several other countries in Africa. The first case outside that continent appeared in Sweden, in a patient who returned from Africa; it’s only a matter of time before a case shows up in the United States, although the extent of a potential U.S. outbreak is uncertain.

To combat the spread of mpox, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have declared a public health emergency. How the world, and the U.S., responds to this latest flare-up will test whether we are at all better prepared to confront global public health emergencies since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The current outbreak in Africa stems from a different, more dangerous mpox variant compared to the last outbreak in 2022. There are no confirmed cases of the strain in the U.S.

The current uptick, primarily driven by a new virus strain, clade I, is different from the 2022 mpox surge, which was successfully controlled by the U.S. and other countries. Unlike in 2022, more than half of reported cases, and most deaths, have been in children younger than 5 years old. During the earlier outbreak, the virus primarily spread through sexual contact among men who have sex with men, whereas the evidence shows the current outbreak spreading through heterosexual and nonsexual contact. In the U.S., the 2022 outbreak was contained by health authorities working with groups including men who have sex with men to increase vaccine uptake and reduce transmission risk; this year’s requires a more extensive approach.

For the U.S. now, waiting to act until clade I cases are detected here will be too late. The best way to control an outbreak is to prevent it.

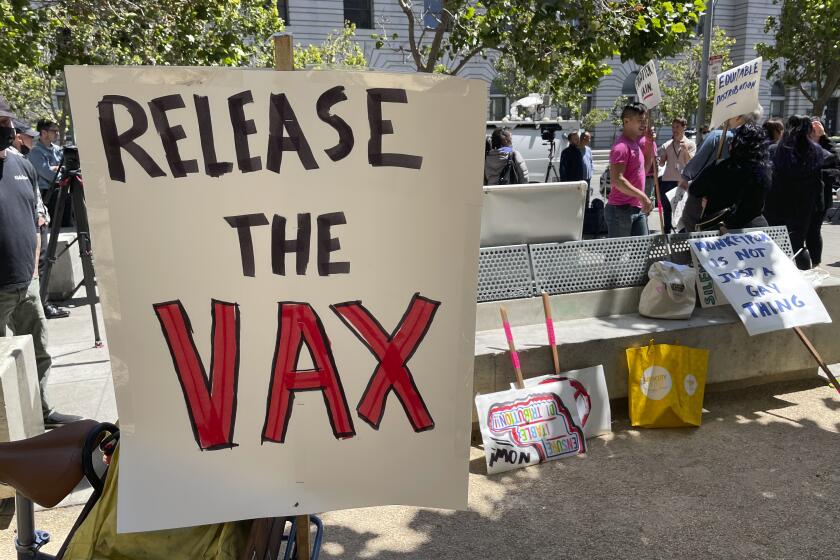

There are a few steps that can help us prepare. Ensuring adequate vaccine supplies should be the highest priority. Danish vaccine manufacturer Bavarian Nordic is one of a few companies in the world with an approved mpox vaccine. Before the 2022 outbreak, it did not have a large inventory of mpox vaccine and doses were produced to order, delaying their availability in 2022 and stymieing outbreak control in the initial days.

The Jynneos vaccine is highly effective in fighting mpox, and rich countries have stockpiled doses. But in Africa, where mpox is endemic, health officials don’t have access to it.

Since then, the company has maintained an inventory of mpox vaccine doses. More than 250,000 doses have been sent to the DRC, and the company indicated that it could produce another 2 million by the end of the year. However, the precise schedule of availability of these doses is uncertain, and the 2 million would cover just a fraction of the doses needed to vaccinate 10 million people in the coming months, according to estimates from the Africa CDC. Meanwhile, wealthy countries, including the U.S. and Canada, have donated or pledged modest amounts of vaccine and have further stockpiles that could provide some emergency donations. Adequate vaccine supplies to Africa to control the outbreak will be essential for preventing broader spread.

Another urgent need is to evaluate the efficacy of the mpox vaccine against the new strain. Previous evaluations have primarily focused on effectiveness against clade II. While it is reasonable to deploy the current vaccine, as it is the best tool available to protect against mpox, a more precise estimate of its effectiveness against clade I will help ensure that the optimal number of doses and the right vaccination schedule are used.

Modest investments in early stages of outbreaks can prevent much larger financial costs associated with widespread epidemics. Failure by high-income countries to ensure that the World Health Organization and Africa CDC have the financial resources to fight this now may result in a much more expensive outbreak in a few months.

Fast-moving outbreaks also have the tendency to increase the spread of misinformation. In the past, public health agencies ramped up their communication efforts only after rumors started taking hold. Evidence from behavioral science supports preemptively “inoculating” the public against misinformation, such as what we’ve seen regarding the COVID vaccine.

There is a window to mount an effective national and global response to control mpox and avoid past mistakes. If we don’t respond within that window, we may have deja vu from our imperfect COVID response, when delays in getting ahead of outbreaks caused so much unnecessary suffering.

Saad B. Omer is an epidemiologist and vaccine expert.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.