Here are the 5 major differences between the House and Senate versions of the GOP tax plan

- Share via

As a House committee prepared to pass one version of a tax bill on a party line vote Thursday, Republicans on a

They noted the bills are largely the same at their heart. Each is centered around a huge cut in the corporate tax rate and makes revisions designed to provide a break to middle-class earners — although independent analyses of the House bill say it benefits the wealthy more than average Americans.

“Yes, the Senate bill is going to be different than the House bill because, you know what, that’s the legislative process,” House Speaker

“But what’s encouraging in all of this is … we have a framework that we established with the White House and the Senate, and these bills are being written inside that framework,” he said.

Here are five major differences between the two bills.

Bracket buster

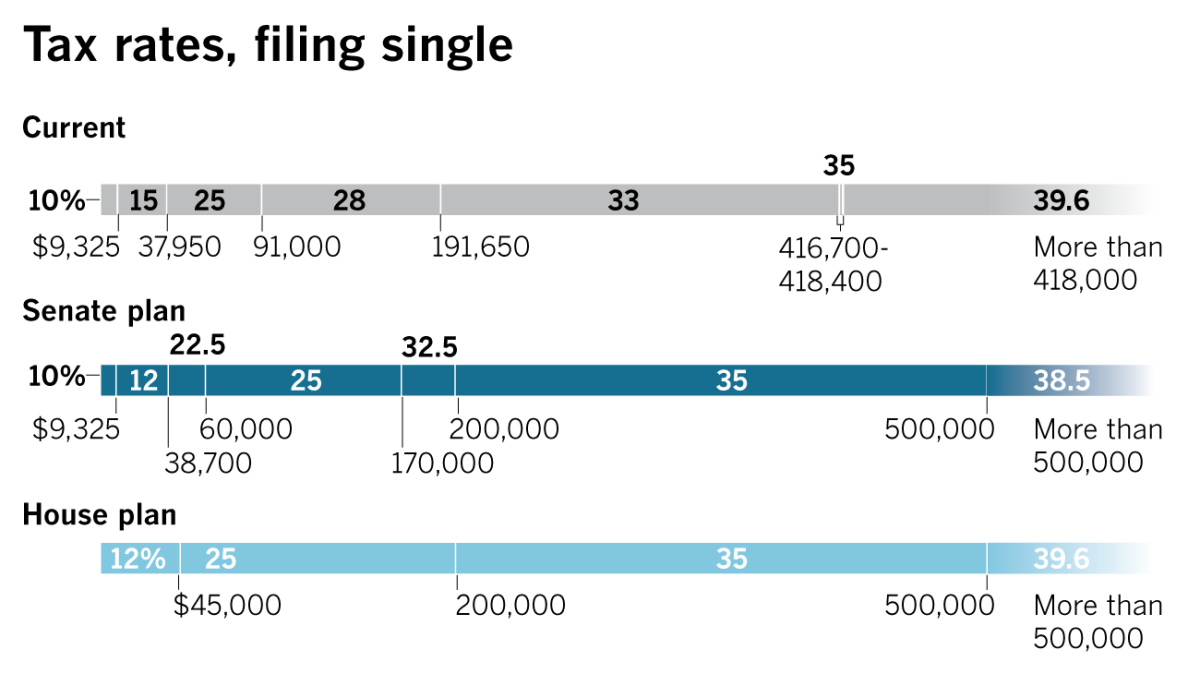

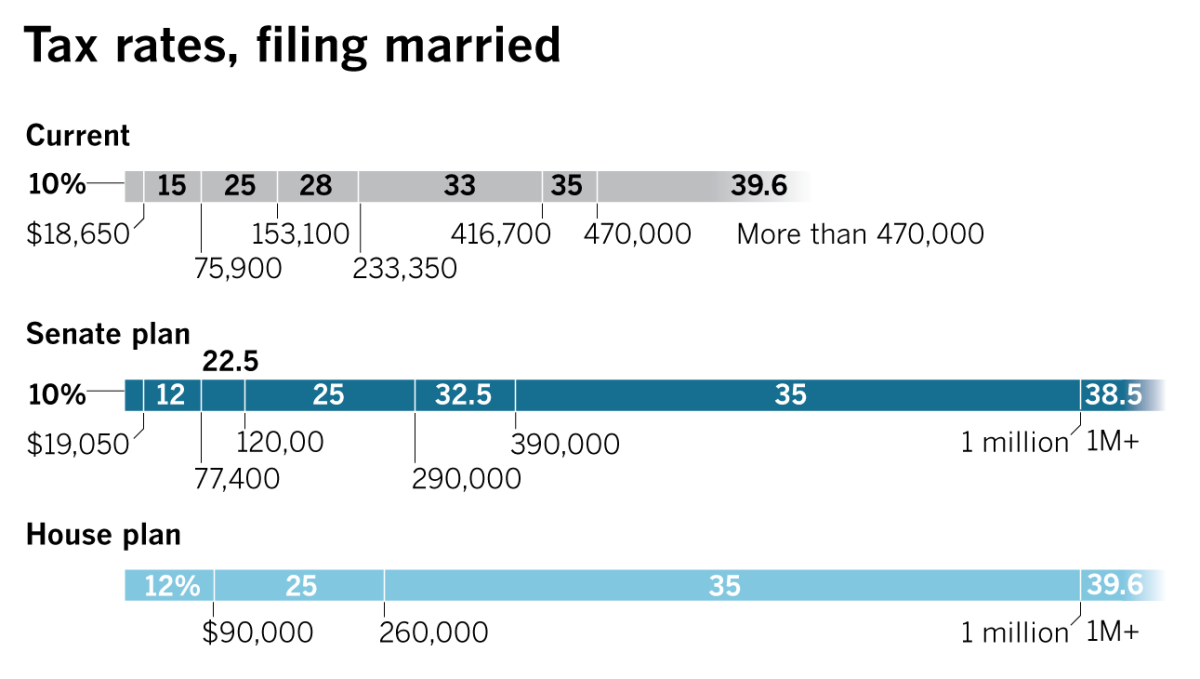

A major goal of the tax overhaul is simplification. A key to that for individuals is shrinking the number of brackets that dictate the marginal tax rate people pay on their income.

That reduction has proved to be difficult as Republican lawmakers have tried to fulfill their promise of providing a break to the middle class.

The tax framework released in September by the White House and congressional Republican leaders proposed reducing the current seven brackets to three: 12%, 25% and 35%.

The major difference was that the top bracket, which applied to income of more than $418,400 for individuals and $470,700 for couples filing jointly, declined from 39.6%.

The framework left open the option of lawmakers adding a fourth bracket to make sure the overhaul “does not shift the tax burden from high-income to lower- and middle-income taxpayers.”

Even before the House bill was released, drafters exercised that option.

They restored the 39.6% bracket but increased the income level at which it kicks in to $500,000 for individuals and $1 million for couples filing jointly.

Senate Republicans were concerned that the House’s four proposed brackets didn’t do enough to reduce middle-class taxes. So they want to keep seven brackets but change some of the percentages.

Under the Senate plan, the new top rate would be 38.5%, and that would have the same income levels as the House bill: $500,000 for individuals and $1 million for couples.

The Senate bill’s new brackets would reduce rates on most income.

“It’s a way of making sure people in the middle really benefit from this,” said Sen. John

Deduction reductions

Another simplification was to reduce the number of individual itemized deductions with the goal of allowing most Americans to file their taxes on a large postcard.

Eliminating deductions also would provide more revenue to offset the cost of tax cuts and keep the bill from adding more than $1.5 trillion to the deficit over the next decade — a budgetary requirement for the Senate to pass the legislation by a simple majority vote.

But one of the reasons tax legislation is so difficult is that every deduction has a constituency.

The September framework called for leaving only two deductions: charitable contributions and mortgage interest. The limit on the mortgage deduction going forward was reduced to the first $500,000 of the loan.

The decision to reduce and limit the deductions immediately caused problems.

Allowed individual deductions and credits

House Bill

- Charitable contributions

- Interest on new mortgages up to $500,000

- Property taxes up to $10,000

- Child tax credit of $1,600 for each child

- Tax credit for expenses of adopting a child

- Family tax credit of $300 for each parent and non-child dependent

- Child and dependent care tax credit

- Earned income tax credit for low- and moderate-income workers

Senate bill

- Charitable contributions

- Interest on new mortgages up to $1 million

- Medical expenses

- Student loan interest

- Uninsured losses from federally declared disasters

- Child tax credit of $1,650 for each child

- Tax credit for expenses of adopting a child

- Child and dependent care tax credit

- Earned income tax credit for low- and moderate-income workers

Some House Republicans from California and other high-cost states balked at eliminating the deduction for state and local income, sales and property taxes. So the House bill tried to appease them by keeping only the property tax deduction and capping it at $10,000 a year.

California House

Realtors and home builders complained about the new mortgage interest limit.

And conservative groups hammered the decision to eliminate the tax credit for the expenses of adopting a child. Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee this week restored that credit.

The Senate Finance Committee opted to eliminate the deduction for all state and local taxes, even property taxes. The additional revenue from that move allowed the Senate bill to keep some deductions the House proposed to ax, including those for medical expenses and interest on student loans.

The deduction for casualty losses would remain but only for those incurred in a federally declared disaster.

The Senate decision to knock out all state and local deductions could cost the votes of some House Republicans.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Vista) already had cited the state and local deduction changes as a reason he opposed the House bill. He was reviewing the Senate bill’s details Friday but said it “may leave us with the worst of both worlds.”

“Under this version, you don’t just have Californians looking down the road to potentially higher taxes without the [state and local tax] deduction, but you’re also delaying all the economic benefits you’d see from the changes in the business tax code,” he said. “That’s a big mistake.”

Corporate tax cut timetable

The centerpiece of the House and Senate bills is a huge cut in the corporate tax rate to 20% from 35%. But they differ on when that would happen.

The House bill would lower the rate in 2018, which is President Trump’s preference. The Senate bill would delay the reduction until 2019.

The corporate tax cut is the single-most costly change in the tax code. It would reduce federal revenue by $1.46 trillion over the next decade. Republicans argue that cost would be offset by increased economic growth, but historically, tax cuts have not produced enough growth to offset their costs.

The Senate’s one-year delay would save the U.S. Treasury about $108 billion.

Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin said a one-year delay is better than a longer one.

Leading business groups have been publicly mum on the proposed delay. But

Business groups and corporate lobbyists have pushed for a reduction as other countries have lowered their rates. The U.S. now has the highest corporate tax rate among the major developed economies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

But many companies pay a lower effective rate — and some pay no U.S. taxes at all — by using deductions in the tax code. The overall tax burden is near the bottom among developed economies.

U.S. tax revenue as a share of total economic output was 26% in 2014, the fourth-lowest of OECD nations.

The state of the estate tax

Republicans have long sought to kill the estate tax, a levy of up to 40% on the assets passed down by wealthy Americans upon their death to their heirs. The House bill would kill it. The Senate bill would not.

Republicans have said what they call the death tax also hits family farms and small businesses while forcing many people to pay for expensive estate planning to try to avoid it.

Democrats counter that the estate tax affects very few people because the level at which it kicks in has been increasing.

This year, the tax hit estates of more than $5.49 million for an individual or $11 million for a couple. There were 12,411 estate tax returns in 2016, but only 5,219 of those owed taxes, according to the

The House and Senate plans would double the exemption next year for the estate tax. Both plans also would double — to $28,000 per person and $56,000 per couple — the annual exclusion from the federal tax on gifts to children or other people.

But the House plan would repeal the estate and gift taxes entirely in 2024. That would reduce federal revenues by about $150 billion over a decade.

The Senate bill keeps the estate and gift taxes in place with the higher exemption levels.

Small-business differences

Republicans have attempted something complicated in their tax plans: providing relief to small businesses. They each do it differently.

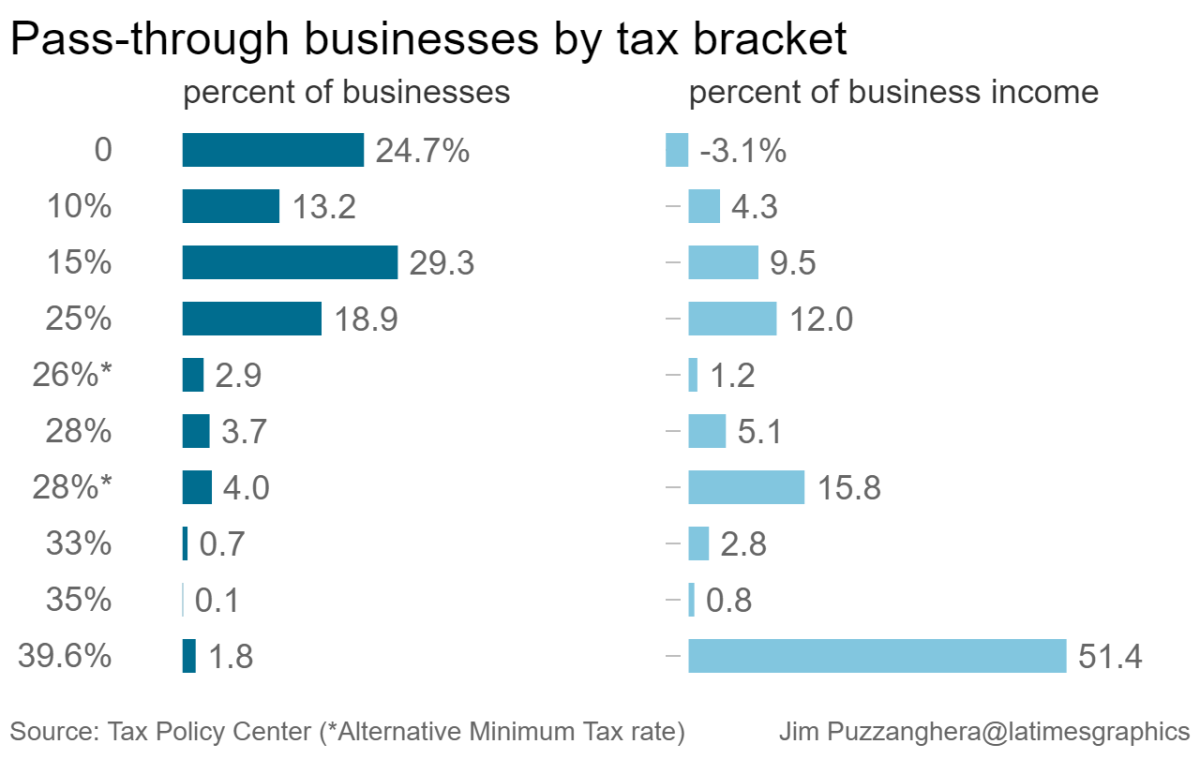

The owners of most of those businesses, known as pass-throughs, pay taxes through the individual code.

The House proposed capping the top tax rate for such entities — sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies and S corporations — at 25%.

The Senate plan would continue taxing pass-through businesses at the individual rate that would apply to the owner, with a top proposed rate of 38.5%.

But to reduce taxes for them, the Senate bill would allow most pass-throughs to deduct about 17% of their business income from their taxes.

Small-business support is crucial to passing the bills.

The National Federation of Independent Business said it was “very encouraged” by the Senate bill.

Last week, the group said it could not support the House bill because most of its members already pay no more than 25% and would not benefit from the reduction in the top rate. (See chart below.)

Responding to those criticisms, Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee made several changes Thursday, including the creation of a new, lower 9% tax rate for the first $75,000 in business income. That rate would be phased in over several years for small pass-through businesses.

Jack Mozloom, a spokesman for the federation, said the group supported the change and was likely to back the House bill, “barring any surprises” in the technical language. The group is still analyzing the Senate proposal and does not yet know whether it is better than the House approach.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.