On an often unpredictable Supreme Court, Justice Gorsuch is the latest wild card

- Share via

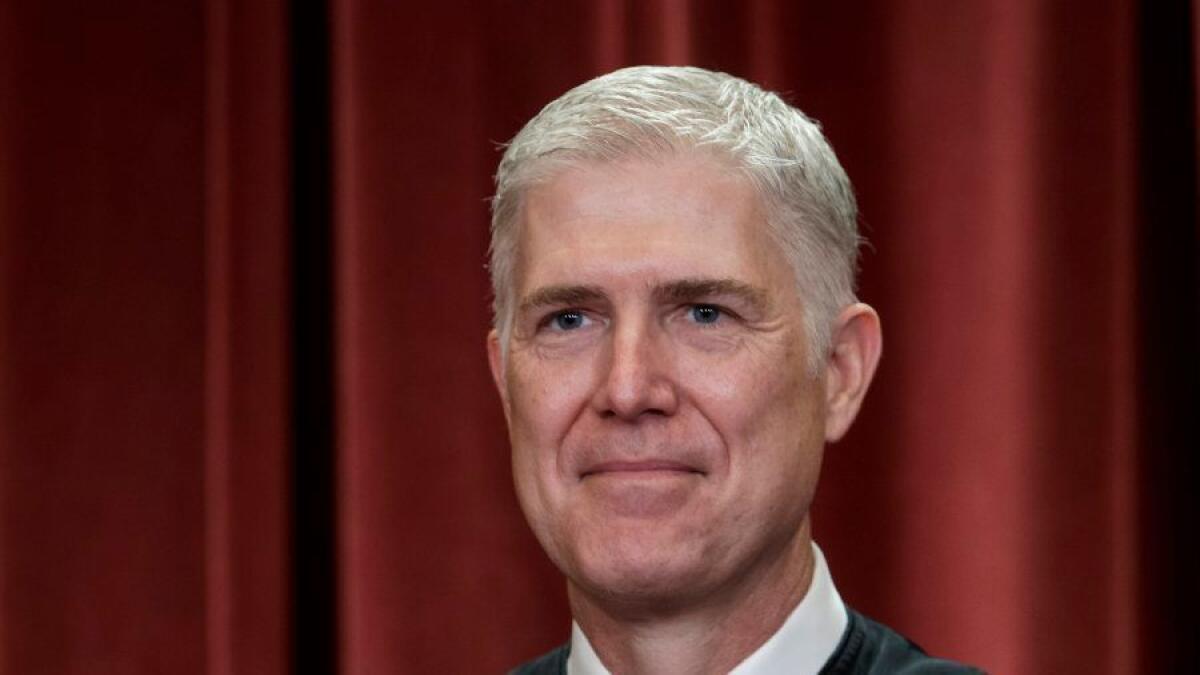

Reporting from Washington — Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, President Trump’s first appointee to the Supreme Court, is proving to be a different kind of conservative.

He is a libertarian who is quick to oppose unchecked government power, even in the hands of prosecutors or the police. And he is willing to go his own way and chart a course that does not always align with the traditional views on the right or the left.

In several of the term’s biggest cases, Gorsuch voted as expected. He joined the court’s conservatives, including Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, to reject legal challenges to partisan gerrymandering. The two Trump appointees voted in dissent to uphold the administration’s plan to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census.

In the case of whether a giant cross on a Maryland highway violated the separation of church and state, Gorsuch took the most conservative position and said lawsuits filed by people who are “offended” but not actually harmed by such things should be tossed out.

But in the last month, he also wrote several broad and bold opinions — mostly in dissent — urging the court to revive the Constitution’s protections for individual liberty. He did so while taking the side of people not usually embraced by conservative justices, including a sex offender from Maryland, an Alabama man who was prosecuted twice for carrying a gun in his car, and two African American men from Texas who were sentenced to more than 50 years in prison for robbing gas stations.

Jonathan Adler, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, calls Gorsuch “a maverick conservative with a libertarian streak. It’s remarkable that he and Kavanaugh disagreed in 30% of the term’s cases. This shows they are quite different types of conservatives.”

Earlier this year, Gorsuch wrote an opinion clearing the way for long-haul truckers to sue their employers over substandard wages, and he wrote dissents in favor of an injured railroad worker who was battling the train line over the damages he won, and a disabled construction worker fighting the Social Security Administration over disability benefits.

“Walk for a moment in Michael Biestek’s shoes,” he wrote in a dissent in the construction worker’s case that was joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and in part by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. “As part of your application for disability benefits, you’ve proven that you suffer from serious health problems and can’t return to your old construction job. Like many cases, yours turns on whether a significant number of other jobs remain that someone of your age, education and experience, and with your physical limitations, could perform.”

At Biestek’s hearing, an expert testifying for the agency said there were 360,000 jobs nationwide that he could perform. “Where did those numbers come from?” Gorsuch asked. When pressed about the source of this data, the expert said it came from a confidential private survey. The agency examiner ruled this evidence was good enough to justify denying Biestek’s claim, and the high court agreed by a 6-3 vote. “Count me” with the lower-court judges who were skeptical, Gorsuch said.

His most important opinion of the term came in a case that was seen as an opening salvo in the war over the “administrative state.” Conservatives have sought to rein in federal regulators, including the Environmental Protection Agency. Liberals are just as determined to defend them. The battle was fought, oddly enough, in the case of Herman Gundy, a sex offender who served five years in prison in Maryland and then moved to New York in 2012.

There, he was charged with failing to register as a sex offender as required under a law adopted by Congress in 2006, two years after his crime. The law said the “attorney general shall have the authority” to decide whether to apply the registration rule to the more than 500,000 offenders like Gundy whose crimes predated it.

Sarah Baumgartel, a federal public defender in New York, appealed Gundy’s conviction, in part, for violating “the non-delegation doctrine.” This refers to the principle that Congress may not delegate its lawmaking power to the president or executive agencies. It’s a doctrine studied in law schools, but not since 1935 has the high court struck down a law on this basis.

But she thought the appeal might interest Gorsuch and other justices, even though it had lost in every lower court. “This has been considered a dead-letter doctrine by many people. But he has a libertarian streak and a greater skepticism about federal power,” she said.

Her instinct was right. The eight-member court heard the case in the first week of October, a week before Kavanaugh was confirmed. But on June 20, the court ruled against Gundy in a splintered 5-3 decision, with Gorsuch writing a 33-page dissent in Gundy vs. U.S.

“The Constitution promises that only the people’s elected representatives may adopt new federal laws restricting liberty,” Gorsuch wrote. “Yet the statute before us scrambles that design. It purports to endow the nation’s chief prosecutor with the power to write his own criminal code governing the lives of a half-million citizens. Yes, those affected are some of the least popular among us. But if a single executive branch official can write laws restricting the liberty of this group of persons, what does that mean for the next?”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with Gorsuch. Justice Samuel A. Alito said he would be willing to accept this argument in a future case. And with Kavanaugh on board, the conservatives would have a majority.

Gorsuch was also on the losing end of an effort to reject the “dual sovereigns” doctrine that allows both the federal government and a state to prosecute a person for essentially the same crime. This double prosecution seems, to some, to conflict with the 5th Amendment, which says: “No person shall … be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy for life and limb.”

The case began in 2015 when a police officer in Mobile, Ala., pulled over Terance Gamble for a damaged headlight and found a loaded handgun in his car. Gamble had an earlier robbery conviction and pleaded guilty to state charges for having a gun in his possession. Later, federal prosecutors also charged him as a felon with a gun, and he was given three more years in prison.

The Supreme Court rejected his double-jeopardy claim on June 17, over dissents by Gorsuch and Ginsburg. “A free society does not allow its government to try the same individual for the same crime until it’s happy with the result,” Gorsuch wrote in Gamble vs. United States. “Unfortunately, the court today endorses a colossal exception to this ancient rule against double jeopardy.… The separate sovereigns was wrong when it was invented, and it remains wrong today.”

But on June 24, Gorsuch spoke for a 5-4 majority to overturn about half of 50-year prison terms given to Maurice Davis and Andre Glover of Texas for robbing four gas stations. They were convicted of the robberies and for brandishing a gun and given long prison terms. They were given an extra 25 years under a 1986 law for conspiring to engage in conduct that, “by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force” will be used.

In United States vs. Davis, Gorsuch said this part of the law is so vaguely worded that no one can tell for sure what it means. “Vague statutes threaten to hand responsibility for defining crimes to relatively unaccountable police, prosecutors and judges, eroding the people’s ability to oversee the creation of the laws they are expected to abide,” said Gorsuch, who was joined by the court’s four liberals. In dissent, Kavanaugh called the ruling a “serious mistake” and said it could mean “many dangerous offenders … might walk out of prison early.”

Brandon Beck, a federal public defender in Lubbock, Texas, who appealed on behalf of Davis, said he tailored his argument to Gorsuch because he “is very concerned by the text and the separation of powers. … He is also very independent, and I have lot of respect for that.”

Progressive lawyers stress that Gorsuch is a reliable conservative on most issues. Brianne Gorod, counsel for the Constitutional Accountability Center, said he “is like the justice he replaced — Justice Antonin Scalia — in more ways than one.”

Gorsuch’s record is exceptionally conservative, she said. But also like Scalia, he has sometimes demonstrated a willingness to part ways with his fellow conservatives in criminal justice cases. “Those votes suggest possible libertarian-liberal alliances may be something to look out for in the terms ahead,” Gorod said.

A Colorado native, Gorsuch has also tilted the court in favor of Native Americans and tribal treaties. In March, he cast the fifth vote with the liberals to rule for the Yakama tribe, which relied on a 1855 treaty in refusing to pay a fuel tax to Washington state for using its highways.

Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion in Washington State vs. Cougar Den, joined by Ginsburg, to explain the history and closed with this passage: “Really, this case just tells an old and familiar story. The state of Washington includes millions of acres that the Yakamas ceded to the United States under pressure. In return, the government supplied a handful of modest promises. The state is now dissatisfied with the consequences of one of those promises. It is a new day, and now it wants more. But today and to its credit, the court holds the parties to the terms of their deal. It is the least we can do.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.