With recession in the rear view, a more upbeat California looks to choose a new governor

- Share via

Standing beneath a radiant blue sky, Mary Cox set aside her broom and counted the blessings of living in California.

Sure, taxes are high — especially compared with Indiana, where she lived a few years ago — and there’s a lot of government red tape, as she’s learned owning a tavern in this charming bedroom community midway between San Francisco and Sacramento.

But crime isn’t a big problem here, the schools in Vacaville are better than they were in Indianapolis and the weather, the 47-year-old Cox said as she smiled at the crystalline morning, couldn’t be finer.

While Cox swept up, her sister and business partner, Anna Louzon, 37, wandered out to the parking lot and joined the conversation. “Certainly there’s a higher cost to living here,” she said. “But anywhere else you live doesn’t have the beach, the snowy mountains and the desert all within a two-hour drive of your house.”

As California chooses a new governor — one of just a handful in the last 40 years not named Jerry Brown — the state seems to be enjoying something unusual in these tumultuous political times: a feeling of relative contentment.

Not to say things are perfect.

Traffic is awful. Housing costs are crazy. Homelessness is acute.

The state’s 1 million-plus undocumented residents are a source of deep contention; some see a drain on taxpayers, others the victims of unwarranted scapegoating.

Still, more than 100 random interviews conducted over the length and breadth of the state — from Redding in the north to Santee in the south, from the Pacific coastline to the edge of the Sierra Nevada — found most saying things are looking up, at least so far as California’s direction is concerned.

Armand Werden sees things improving from his perch in the Central Valley.

“They’re fixing the streets,” said the 29-year-old community college student, who mans the taps at Dust Bowl Brewery, a sprawling restaurant and gathering spot in downtown Turlock. “The city itself is looking a little bit cleaner. A lot of businesses are opening up.”

Rob Schroeder said after years of upheaval, the entertainment industry is thriving.

“There are people shooting and for California’s economy that’s what matters,” the 45-year-old filmmaker said over a bacon-and-eggs breakfast in the Hollywood Hills. “How people watch it isn’t as important as how many people show up to work every day with a camera or a makeup chair.”

This is far from the angry electorate that heaved Democratic Gov. Gray Davis from office in a 2003 recall, gambling on the upstart Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger, or the economically shell-shocked voters who elected Brown in 2010, doubting that he — or any politician, for that matter — could rescue a state in seemingly steep and irreversible decline.

Since then, the turnabout has been dramatic.

California faced a $27-billion deficit when Brown took office and unemployment was 12.2%, topping 25% in some rural areas. More than 1.3 million jobs were lost in the recession, as the housing and construction industries tanked during the worst economic downturn in 50-plus years.

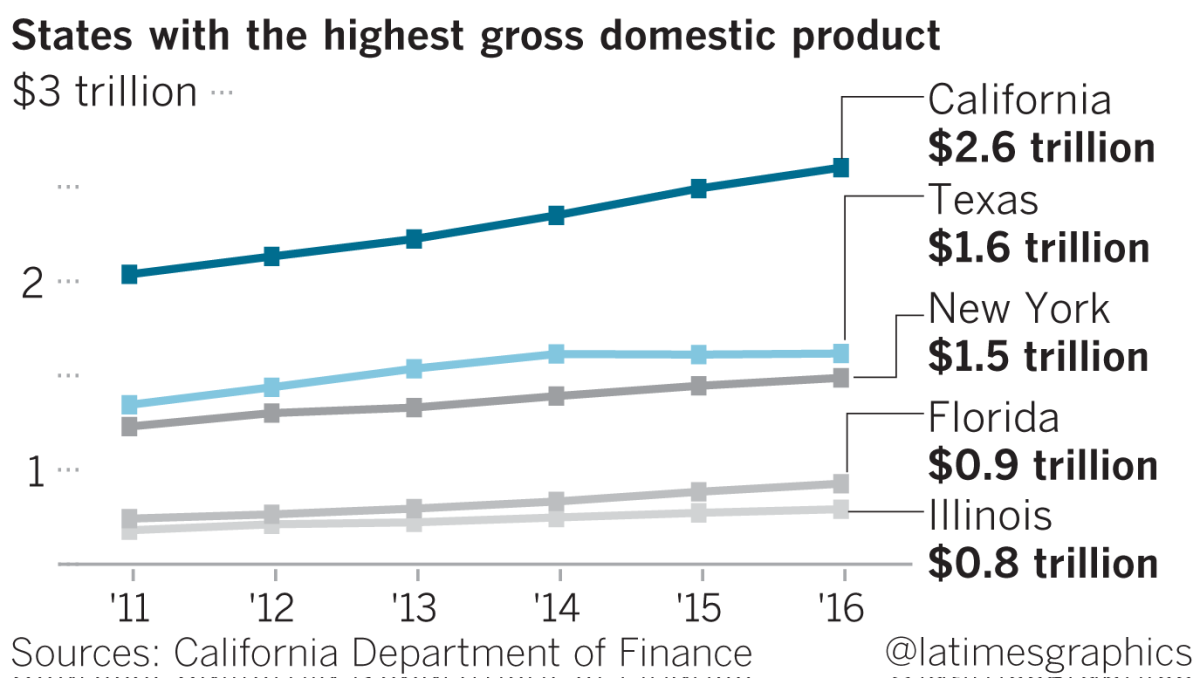

Today, California is running a $6-billion surplus, thanks in part to two voter-approved tax hikes, and the most recent report put the state unemployment rate at 4.3%, an all-time low. Nearly 3 million jobs have been created since the economy bottomed out, a recovery that has outpaced the rest of the country.

Karina Sotto, 25, a community college student who lives in Lennox, just east of Los Angeles International Airport, pointed to the NFL stadium under construction in nearby Inglewood and the fact her father, a welder, made enough money these last few years to finally retire. “We’re on the right track,” she said.

The comparative good times, however, have brought their own set of problems.

“We all don’t make what dot-coms make. You got to be a two-, three-income home to get a one-bedroom nowadays.”

— Karesha McRae, a 33-year-old Menlo Park resident

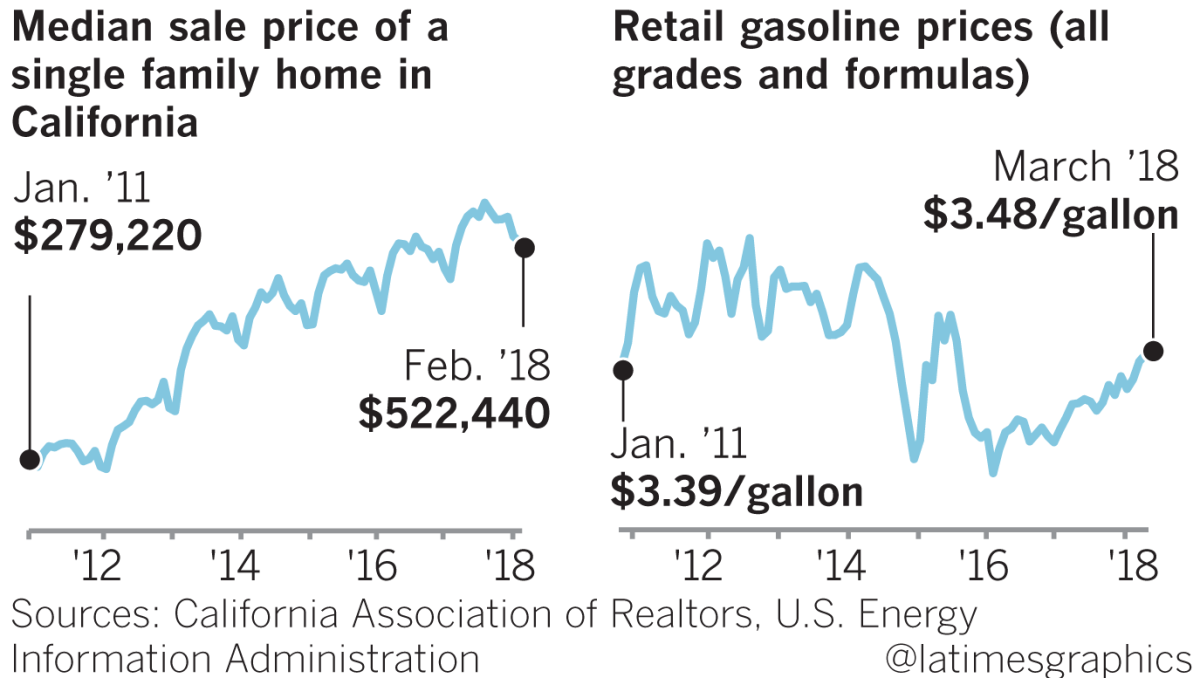

More people working means more people crowding the roadways and packing public transit, turning the daily commute into a form of torture. A robust housing market means higher prices, and the yawning gap between rich and poor means some people are being priced out of their neighborhoods, or forced to surrender more of their paycheck to keep a roof over head. In the worst cases, they’re being shoved onto the streets.

Karesha McRae, 33, is stretched thin living in Menlo Park, where Facebook is headquartered and the median home sale price, according to the website Zillow, is $2 million. McRae, who drives a grocery delivery truck, shares a two-bedroom townhouse with a sister, their parents and her son, where they pay $3,500 a month — a bargain compared with the median $4,100 rental.

“We all don’t make what dot-coms make,” said McRae, as her 9-year-old patrolled second base on the diamond at East Palo Alto’s Martin Luther King Park. “You got to be a two-, three-income home to get a one-bedroom nowadays.”

Affordability is not just an issue in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Eight years ago, Donna Weese, 57, moved from the Santa Cruz area to Shingletown, a speck in rural northeastern California where rent for her one-bedroom cabin will soon climb to $850 a month. She sees residents from the San Francisco Bay Area bringing their wealth to the woods, purchasing rustic second homes and creating a ripple effect pushing her closer to the margins; Weiss, who lives on disability, plans to move into an old motor home and park at nighttime where she can.

“It’s hard,” she said, as an occasional wayfarer whooshed past on Highway 44, the road to Lassen National Forest. “It’s almost impossible to live.”

But dire as it is for some, the issues that came up repeatedly in conversation — overburdened roads, bridges and waterworks; the uneven spread of increased affluence — are different from those facing California eight years ago, when the state was flat on its back, pessimism abounded and many were scrambling to find work and simply stay afloat. Better times mean less gnawing concerns, and that may help explain why so few have paid attention to the governor’s race.

The major candidates — several of them public figures for years — have debated more than a half dozen times and collectively spent millions of dollars campaigning. Still, they remain a mystery less than two months before the June 5 primary; the overwhelming majority of those interviewed could not identify a single candidate who was running.

A few thought Kamala Harris was in the race. (Actually, the Democrat was elected California’s junior U.S. senator in 2016 and is eyeing a 2020 bid for president.) Several said they were inclined to vote for Brown to serve another four years. (Term limits prevent him from seeking reelection.)

Of those who could name a gubernatorial candidate, or maybe two, most leaned toward the Democratic front-runner, Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Julie Caffey said as a lesbian she had a soft spot in her heart for the former San Francisco mayor, owing to his pioneering support for same-sex marriage when he presided at City Hall. “But it’s more like I’ve kind of dog-eared the page” pending further study, said the 58-year-old Democrat, an administrator at California College of the Arts in Oakland.

For many, the enormity of Donald Trump’s presidency has been like a solar eclipse, blotting out anything unrelated to the administration, its outsized dramas and his obvious animus toward California, keeping them on permanent edge.

“Every day in the news it’s just crazy, crazy, crazy,” said Catherine Cherry, 69, who owns a Vacaville real estate business just a few doors down Main Street from the tavern run by the two sisters, Cox and Louzon. “We need stability back.”

Gail Varhoe, 68, confessed to being “totally focused on the country and what’s going on” at the national level, to the exclusion of pretty much everything else. “I haven’t even hardly paid attention to the governorship of California,” the retired corporate executive said as she headed to a doctor’s visit in Loma Linda; she vowed to be up to speed by the time the primary rolls around.

For some Republicans, an utter lack of interest in the governor’s race has nothing to do with Trump, but rather the state’s strong leftward leaning. “It’s going to be a Democrat,” said Bill Johnson, 64, a trucker in Red Bluff, as snowy Mt. Lassen peeked over his shoulder. “So I don’t care.”

That seems to be a safe assumption. It’s been 12 years since Schwarzenegger was reelected and no Republican has won statewide office since. Nothing suggests wholesale change this November either.

Asked what the next governor should focus on, most responded with a fairly standard list: Fix the roads. Ensure schools are amply funded and communities are safe. Do something about the homeless problem. Set a more high-minded political tone.

“I want to see government working together,” said finance executive Robert Maxwell, 56, of Newport Beach, who took advantage of a sunny Friday to skip work and take a 20-mile bike ride along the ocean. “Just a common-sense government. I just don’t want to see crazy things going on.”

More than a few offered one other thought.

They described California as a special place, more welcoming and broad-minded than most. The diversity, they said, and acceptance of differences are a source of strength and something fundamentally worth protecting, like clear skies and clean water.

“I could go to a place where it’s cheaper,” said Helena Dillon, 55, who gets an earful about taxes and the high cost of living as a clerk in the Tehama County assessor’s office in Red Bluff. But she cherishes what she called “California values” — “not us-versus-them,” as she described it, but rather “we’re all in this together.”

It’s worth the price, she said, and something she hopes and expects the next governor to fight for, whomever that turns out to be.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

Twitter: @philwillon

Barabak reported from Northern California and Willon from the Central Valley and Central Coast. Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report from Silicon Valley; staff writers Paloma Esquivel, Melissa Etehad and Michael Finnegan as well as Joshua Stewart of the San Diego Union-Tribune contributed from Southern California.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.