California Legislature releases a decade’s worth of records on sexual harassment investigations

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Eighteen alleged cases of sexual harassment, including sharing of pornographic photos and a staff member accused of grabbing a woman’s buttocks and genitals, were publicly disclosed by the California Legislature on Friday, detailed through investigation records that had been shielded in some cases for more than a decade.

Four incumbent lawmakers are named in those completed investigations: Assemblyman Travis Allen (R-Huntington Beach), state Sens. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) and Tony Mendoza (D-Artesia) and Assemblywoman Autumn Burke (D-Marina del Rey). A fifth completed case named former Assemblyman Raul Bocanegra (D-Pacoima), who resigned last year after facing allegations of harassment by multiple women.

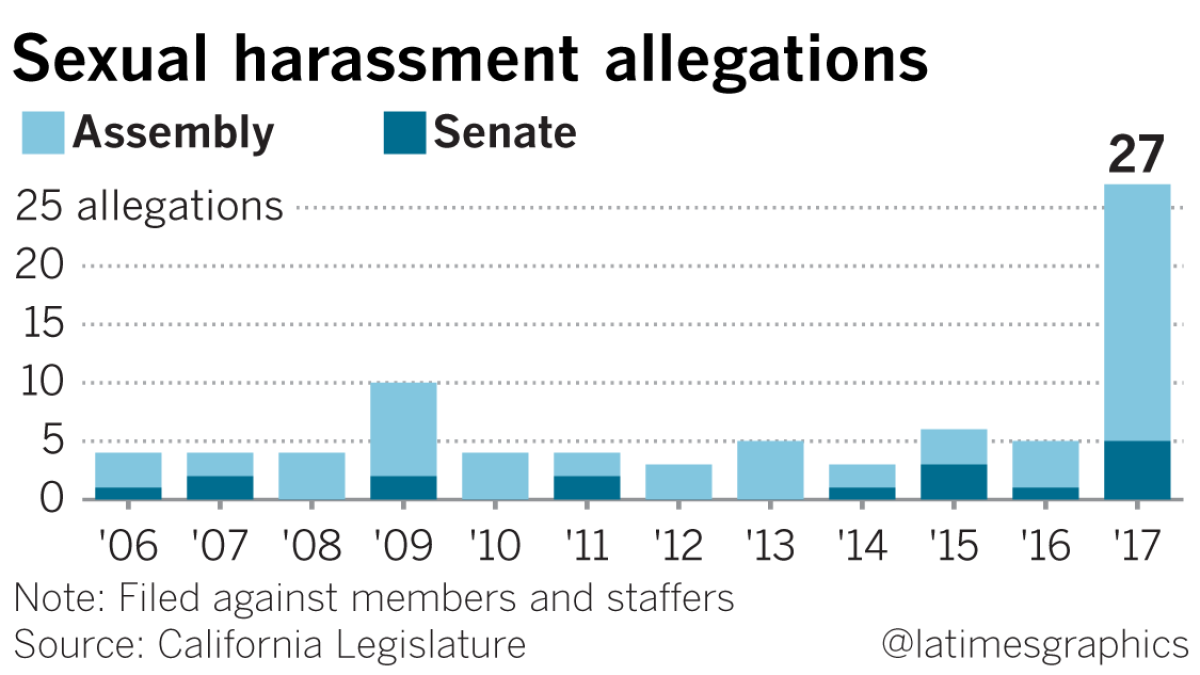

In addition to the lawmakers, 12 senior staff members were accused of sexual harassment or misconduct in substantiated cases. Officials said in total there were more than six dozen complaints recorded by the two legislative houses since 2006.

The information was provided after three months of requests from Los Angeles Times reporters and attorneys. The records provide the most detailed information, to date, of workplace sexual misconduct investigations at the Capitol in Sacramento and legislative district offices across the state.

Read the claims from the California Assembly »

The disclosures mark a major departure from the tradition of the Legislature, which rarely grants access to information about its internal operations. The documents also underscore the wide range of behavior that falls under the umbrella of sexual harassment, from bawdy office banter to unwanted propositions or uninvited touching.

Allen, a Republican candidate for governor, was accused by an unidentified staff member of several instances of contact in early 2013 that made her feel “uncomfortable.” Hertzberg, too, was accused of contact — hugging — that worried a female staff member. Burke was accused by a former aide of sexually explicit talk in the workplace.

Both houses proclaim “zero tolerance” for sexual harassment. The Assembly’s employee manual defines harassment as being marked by “unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other visual, verbal, or physical conduct of a sexual nature.”

The limits of a zero-tolerance policy are evident. One Senate staffer was told his inappropriate comments were “grounds for immediate termination” but instead was given “one final chance” to stay on following a two-week suspension. Another Assembly staffer was not fired for looking at pornography and exchanging sexually explicit photos on a work computer because of his “lengthy” tenure. Instead, he was demoted from a supervisorial role.

Read the claims and settlements from the California state Senate »

Have you experienced sexual harassment in government or politics? Share your story »

The incidents alleged in the documents span from January 2006 through the end of 2017 and were identified by legislative officials as cases in which “discipline has been imposed or allegations have been determined to be well-founded.” That phrase is similar to what The Times requested in November. The documents pertain to closed cases and do not include pending allegations.

The incumbent lawmakers named in the documents denied any wrongdoing when contacted by The Times. Allen, who has served in the Assembly since 2012 and is now running for governor, accused Democratic leaders in the Legislature of a “political attack.”

“I’m sure I’ve shaken many people’s hands, tapped many people on the shoulder, and have even tapped people’s feet accidentally,” he said in a statement. “But there has never been anything in any of my actions that has been inappropriate, and nor will there ever be. I was actually shocked 6 years ago that any friendliness I displayed was in any way misconstrued. Everyone deserves to work in an environment free from inappropriate behavior.”

The newly revealed complaint against Hertzberg was from 2015. A Senate document alleges that he “pulled the employee close to him and began to dance and sing a song to her” in a way that the staffer felt was “uncomfortable and unwelcome.”

“I hug people as a way to connect. It’s never meant as anything other than a gesture of warmth and humanity,” Hertzberg said in a written statement. “This instance, a settled matter from several years ago, involves a single hug with a family member of someone I knew, and I’m sorry to her and anyone else who may have ever felt my hugs unwelcome.”

Hertzberg is known in political circles as “Huggy Bear” for his frequent embraces. An investigation into his actions is underway, prompted after former Assemblywoman Linda Halderman of Fresno complained about hugs from Hertzberg. The Republican, who served from 2010 to 2012, said Hertzberg had repeatedly embraced her in a manner that made her uncomfortable.

Mendoza, too, is the subject of a current investigation, after claims of unwanted advances toward three former female subordinates. He is on a leave of absence from the Senate while the accusations are examined and has denied any “inappropriate bodily contact” with the women. Mendoza has also been sharply critical of the Senate’s investigation process. An outside law firm is conducting the current investigations of Mendoza and Hertzberg.

The case involving Burke, elected to the Assembly in 2014, was sparked by an accusation from a former staff member in 2017. The then-Assembly human resources director found that Burke had an “inappropriate conversation regarding anal sex with Capitol office staff.” In a statement, the Democratic assemblywoman said the conversation occurred “after-hours” and involved a staff member sharing his experience as a young gay man. She said the claim was later made by a “disgruntled former staff member.”

“As a leader, I recognize my obligation to ensure a safe and comfortable work environment for everyone in my office, and I think every claim needs to be taken seriously,” Burke said. “However, I believed then and still believe that the complaint was motivated by the former staff member’s anger over being terminated.”

The newly released complaints were provided to The Times 94 days after legislative attorneys initially refused to do so, a position that lawmakers reconsidered after the newspaper’s attorneys warned that a California court could ultimately be asked to intervene. “Any privacy rights in such cases must yield to the public’s profound interest in learning the basis of the claims, the process followed … and the resulting discipline or other resolution,” Jeff Glasser, The Times’ vice president for legal affairs, wrote in a Dec. 5 letter.

The chief of staff to Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) said that future records will be released under the “custom and practice” of the house — a set of nonbinding guidelines — and then only upon formal request. Assembly officials said they haven’t determined the procedure going forward.

In several instances, staff members were fired after an investigation. One Assembly staff member, however, stayed on the government payroll after an investigation in 2007. In 2015, he was again accused of inappropriate workplace behavior.

Only the original complaint and documents confirming each investigation’s completion were made public. The names of accusers and witnesses were excluded, and lawmakers refused to disclose any other records pertaining to the cases.

Based on numbers initially provided to The Times last fall, the new documents show 58% of sexual misconduct investigations in the Legislature since 2006 resulted in a verified complaint or discipline. Absent additional disclosure, it’s difficult to make any broad assessment of sexual harassment accusations in the legislative workplace.

California’s Legislature investigated 31 abuse complaints made over the past decade »

For example, the disclosure was limited to cases involving “high-level” staffers, usually legislative employees who manage other workers. Because sexual harassment isn’t limited to supervisors acting improperly toward a subordinate — a receptionist, for example, could be found to have sexually harassed an office assistant — it’s possible additional incidents are being kept confidential.

The documents also included the cost to taxpayers. For investigations into sexual harassment, the Legislature spent more than $294,000 on outside attorneys. And on the cases that ended in cash settlements, legislative officials agreed to payments totaling $290,000.

The current spotlight on the issue of sexual misconduct likely explains why there are more ongoing investigations in the Capitol than at any time in recent history. A spokesman for Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Paramount) said there are eight pending inquiries, including the publicly acknowledged allegations against Bocanegra and former Assemblyman Matt Dababneh (D-Woodland Hills). Both men resigned last fall after accusations of harassment from multiple women. Bocanegra and Dababneh have denied any wrongdoing. The Assembly declined to identify the subjects of other ongoing investigations, which include members and senior staff.

The records provide new information about a 2009 incident involving Bocanegra, who was then a legislative staffer and later elected to the Assembly. The Times reported last year that Elise Flynn Gyore, a fellow staffer at the time, alleged Bocanegra made “inappropriate and unwelcome physical contact” with her by sticking his hands in her blouse at a nightclub. The records released Friday show that Bocanegra was suspended for three days without pay after an investigation found that the encounter “more likely than not” happened. He also was directed to undergo individual counseling and training.

The records show that Bocanegra at the time speculated that the complainant had a political motive for the complaint, but the investigation found no evidence that Gyore would fabricate her claim for a political reason. Bocanegra resigned from the Assembly last year after The Times reported on the Gyore complaint and allegations from six additional women of inappropriate sexual behavior.

Coverage of California politics »

A spokesman for De León initially said investigations into Hertzberg and Mendoza are the only pending sexual harassment cases involving senators or high-level staffers. De León’s office later said there is a third senator under investigation, but declined to identify the lawmaker.

The Legislature’s handling of sexual harassment complaints has faced unprecedented public scrutiny in the wake of an open letter last October, signed by more than 140 women in California politics and denouncing a “pervasive” culture of sexual misconduct in their industry. In response, lawmakers scrambled to address what critics called a confusing and inconsistent process for handling complaints. They convened a joint legislative committee tasked with recommending changes to harassment policies that would be implemented uniformly by the Senate and Assembly — a significant change for two houses that operate their own human resources operations.

“As has already been made clear, the Legislature needs to do a better job making sure everyone in the Capitol community feels safe in their jobs & safe coming forward with complaints,” Rendon wrote in a tweet late Friday.

Gyore, who was praised last year for her decision to come forward with accusations against Bocanegra, agreed.

“I don’t think we’re all done with everything,” she said. “We have work to do...The best outcome is we create a culture in which this doesn’t happen in the first place.”

Times staff writer Patrick McGreevy contributed to this report.

Follow @johnmyers and @melmason on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

Read the claims from the California Assembly

Read the settlements from the California Assembly

Read the claims and settlements from the California state Senate

Have you experienced sexual harassment in government or politics? Share your story

UPDATES:

5:20 p.m. This article was updated with comment from Speaker Rendon and from Elyse Gyore.

4 p.m.: This article was updated with a comment from Allen and more details from the documents.

2:10 p.m.: This article was updated with the number of senators currently under investigation.

This article was originally published at 1:40 p.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.