Column: To this impeachment ‘connoisseur,’ Trump’s case looks familiar

- Share via

WASHINGTON — In 1998, when House Republicans set out to impeach President Bill Clinton for lying about sex, they claimed lofty ambitions.

“This has to be a bipartisan exercise,” Rep. Henry J. Hyde of Illinois, then chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, told me back then.

He failed. His committee produced four articles of impeachment, all but one on strict party lines. The full House approved only two: perjury and obstruction of justice. The Republican-led Senate acquitted Clinton of both charges; no one in the president’s party voted against him.

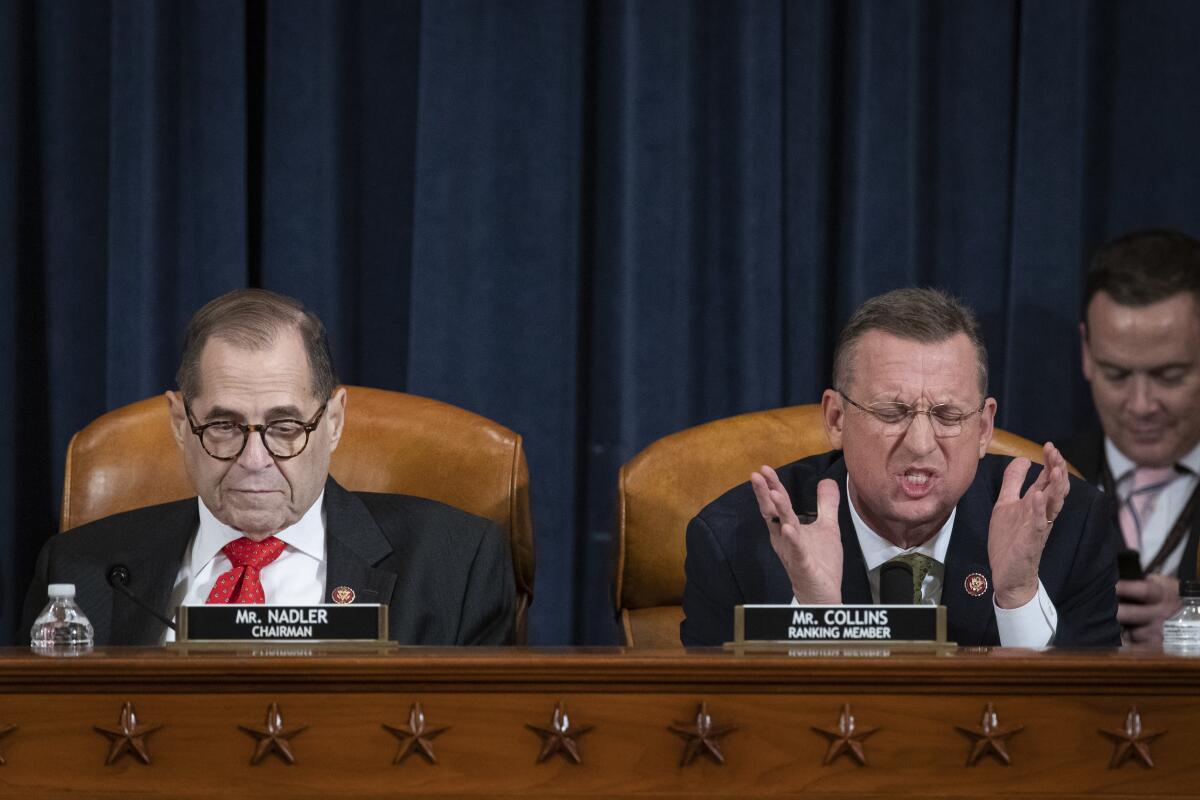

History repeated itself last week in mirror image. This time the president was Donald Trump, and the committee chairman was Rep. Jerrold Nadler, a New York Democrat. Just as in Clinton’s day, members of the majority party pleaded with the president’s supporters to wrestle with their consciences.

But no Republican broke ranks. No consciences were wrestled — not visibly, anyway. Just as with Clinton, Congress is heading for impeachment on a near party-line vote.

Back then, the House included mavericks, fiercely independent members who sometimes ignored the wishes of party leaders. In the full House vote in 1998, five Democrats registered their distress at Clinton’s conduct by voting yes for at least one article of impeachment.

With Trump, not one of the 197 House Republicans is expected to vote in favor of impeachment. A half a dozen Democrats may vote no, but they’ll have permission from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) because they face reelection in Trump-friendly districts.

So while last week’s acrimonious Judiciary Committee hearings sounded as if they were aimed at wooing potential defectors, nobody expected any votes to change.

Instead, all of those five-minute diatribes were aimed at the public, which is split right down the middle: Democrats favor impeachment, Republicans oppose, independents are divided.

Ambitious House members got to show off their oratory — from Matt Gaetz, the ferociously loyal Trump defender from Florida, to Eric Swalwell, the East Bay Democrat who briefly ran for president this year.

Each side got to make its case before history. The outcome was never in doubt, but the performances were still worth watching —whether in person, as I did for part of the proceedings, or on television. (I sat through Hyde’s hearings in 1998 and attended the Watergate hearings in 1973, so I consider myself a connoisseur.)

It wasn’t an even fight. Democrats had most of the facts on their side, even though their prosecution came with a flaw.

They presented a clear case of presidential abuse of power: Trump publicly asked Ukraine and China to investigate Joe Biden, a Democratic candidate for president. The president blocked military aid to Ukraine for 12 weeks while he pressed his demand. Those facts are not in dispute.

Here’s the flaw: The Democrats’ case against Trump would be stronger if they had gone to court to enforce subpoenas against administration witnesses, including the acting White House chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney.

But those court fights could have taken a year or more — and Trump has made clear that he wants to run out the clock past the presidential election 11 months from now.

Pelosi and Nadler chose not to wait. They don’t want impeachment to interfere with their 2020 campaign to hold on to the House. They also argued that impeachment is the only way to deter Trump from seeking further foreign help with his reelection campaign.

The Republicans responded with a barrage of objections — some relevant, some not. They contested every fact, even some based on Trump’s public statements.

They argued that “abuse of power” isn’t grounds for impeachment, although the constitutional scholar they called as a witness said it is. They argued that Trump was crusading against corruption in general, but never explained why the only investigations he asked for focused on Biden and other Democrats.

When all else failed, they brought up the name of Biden’s son Hunter, who worked for an unsavory Ukrainian energy company.

It didn’t hang together. But the GOP is hamstrung by Trump’s insistence that his conduct was “perfect.” That didn’t leave Republicans room to argue that while he may have gone too far in muscling Ukraine, his misconduct doesn’t merit impeachment.

The only thing likely to change when the full House votes this week is the decibel level. Pro-impeachment demonstrations are planned in Washington and more than 400 other cities to stiffen Democrats’ spines and worry Republicans.

The Senate trial, expected in January, will be more dramatic. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. will preside; prosecution and defense teams will present evidence, arguing on roughly equal conditions. There may be a fight over Trump’s demand that the Senate call witnesses, including Hunter Biden. A few jurors could flip sides, including Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.).

Even so, the outcome isn’t in doubt. Removing a president requires a two-thirds majority, which means 20 GOP senators would have to switch sides. That won’t happen.

Besides, the foreman of the jury, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), has boasted that he’s collaborating with the president’s lawyers.

That doesn’t mean the proceedings will be inconsequential. Trump’s prestige and legacy will be on the line. Every Republican defection, if any, will be a blow to his self-regard. And when it’s over, he will have earned impeachment as a permanent stain on his record.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.