What are the Iowa presidential caucuses and why are they so important to the 2020 election?

- Share via

DES MOINES — The Democratic presidential contest has been well underway for more than a year. After months of hearing from the candidates and pundits, voters will finally have their say beginning Monday at the Iowa caucuses.

It’s the first nominating contest in the nation, and it will shape the momentum of the race. The results can provide a breakout moment for an unlikely candidate — or end a campaign. The caucuses are also complicated and controversial. We break it all down for you.

What is a caucus?

Most Americans, including Californians, take part in a traditional primary election, in which a voter casts a secret ballot by mail or at a polling place before or during set hours on election day. In Iowa’s Democratic caucus, voters gather at churches, homes, schools or other community spots at a set time and publicly select their preferred candidate.

How does it work?

The caucus process varies by state and by political party.

Iowa Democrats will meet at 7 p.m. local time on Monday at 1,678 precincts across their state. A supporter for each candidate will make a pitch. Voters will then physically gather with others who support the same candidate. A caucus attendee who has not settled on a candidate can gather with other undecided voters.

After this first “alignment,” officials will determine whether a candidate is “viable.” To be deemed viable, a candidate must have the support of at least 15% of the people in attendance in the precinct. If a candidate does not get to 15%, those supporters are then free agents, and can choose one of the viable candidates, team up with the supporters of another nonviable candidate, join the undecideds or call it a night and go home.

Look for lots of bargaining, cajoling and pleading as supporters try to court newly free voters to run up their preferred candidate’s numbers.

After this second round, the results are locked in, and officials use the final tallies to determine how many “state delegate equivalents” each candidate is awarded.

Post your question in the comments below and we may answer it during our live coverage Monday.

How are delegates awarded?

For candidates who make the 15% viability cut, 2,107 “state delegate equivalents” will be awarded proportionally by precinct on caucus night. Then, the party holds a series of conventions that eventually lead to the election and proportional allocation of the state’s 41 pledged national delegates who will head to the Democratic National Convention. (The state has an additional eight non-pledged delegates comprising five Democratic National Committee members and Iowa’s three Democratic members of Congress.)

To win the nomination, a Democrat needs the backing of a majority of the 3,979 pledged national delegates at stake at the convention.

What’s new in the 2020 Iowa caucuses?

Lots.

The state party is limiting the caucus alignment to two rounds before locking down the results. Additionally, if a voter’s preferred candidate is deemed viable in the first round, the voter can leave and that vote still counts. These changes are intended to cut down the time the caucuses take.

The state party also created 87 satellite caucuses for Iowa Democrats who can’t attend their assigned precinct on Monday. There are 60 in Iowa, as well as 24 in other states and three in other countries. Two of these satellite caucuses are taking place in California — in Palm Springs and Stanford. The total number of state delegate equivalents awarded from the satellite caucuses will be between 23 and 216, depending on how many people participate in these alternate sites. (This is on top of the 2,107 state delegate equivalents awarded through the traditional precincts.)

The Iowa Democratic Party plans to release caucus results in a new format. In past years, they released only the number of state delegate equivalents each candidate was awarded. This is the most important number. Once the results are tallied, the Democrats also plan to release raw vote totals from the first and second rounds of voting. This change is a result of criticism from Bernie Sanders’ 2016 supporters, who argued that their near-mirror finish in delegates with Hillary Clinton masked the popular support he had in the caucuses.

Here are key dates and events on the the 2020 presidential election calendar, including dates of debates, caucuses, primaries and conventions.

Won’t it muddy the results if one wins the most delegates and another the raw vote total?

It’s possible. Each campaign that does well in either of the three results will argue its candidate won, and there is a slim mathematical possibility that the candidate who wins the most delegates will not be the candidate who had the most supporters.

Why does such a small homogeneous state get such an oversized role?

Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status is the end result of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which was marred by conflict in the convention hall, and racial and Vietnam War protests and violence in the streets. Party leaders decided to turn away from a top-down process of selecting nominees and instead move toward a voter-driven process that was viewed as more democratic. Iowa had long held caucuses, but the state’s months-long delegate selection process resulted in it being selected to go first. Republicans soon followed suit.

The caucuses have long drawn criticism. They take place at a set time in the evening, so they preclude the participation of some Iowans, such as night shift workers. The new Democratic satellite caucuses are designed to address this.

The number of participants is dismally low. In 2016 — a contest when both the Democratic and Republican nominations were up for grabs — fewer than 358,000 Iowans caucused, less than 16% of those eligible to vote.

To put that number in perspective, more than 8.5 million Californians voted in the two parties’ 2016 presidential primaries, or 47.7% of the state’s registered voters. Iowa caucus supporters argue that it is critical for candidates to be able to make their case to voters in person, and in states that don’t require massive media buys.

Then there is the dearth of minority voters in a rural state kicking off the nomination process for the party that represents the majority of minority voters and urbanites. Iowa, and the state that follows it in the nominating process, New Hampshire, are both more than 90% white. Critics have long argued that neither is representative of the nation as a whole.

The party attempted to address those concerns in the lead-up to the 2008 presidential campaign, when the Democratic National Committee added Nevada, with a large Latino population, and South Carolina, with a large African American population, right after Iowa and New Hampshire.

Though Iowa Democrats and Republicans don’t agree on much, they zealously guard Iowa’s status as the first nominating contest in the nation. They have worked together to make sure their national parties don’t stray.

Democrats increasingly worried about the prospect of Bernie Sanders winning their nomination are pushing harder to block him, galvanizing his backers in the process.

Are the Iowa caucuses predictive of who will win the White House?

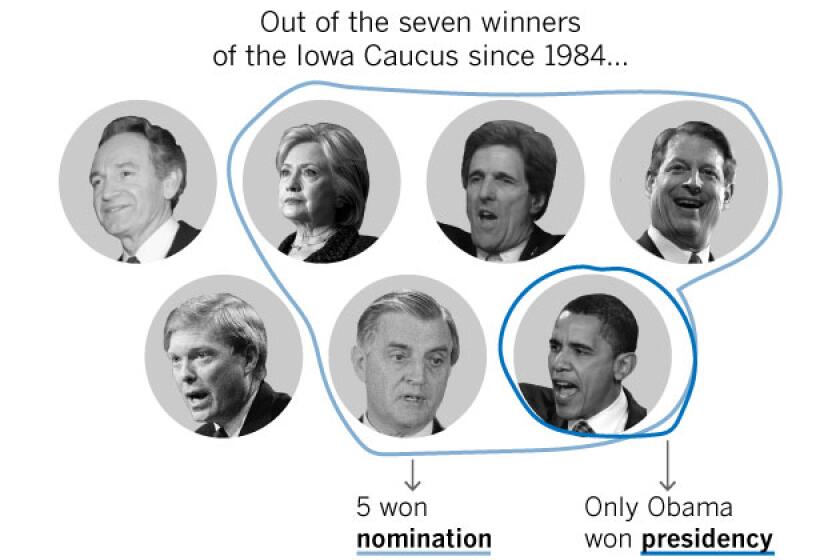

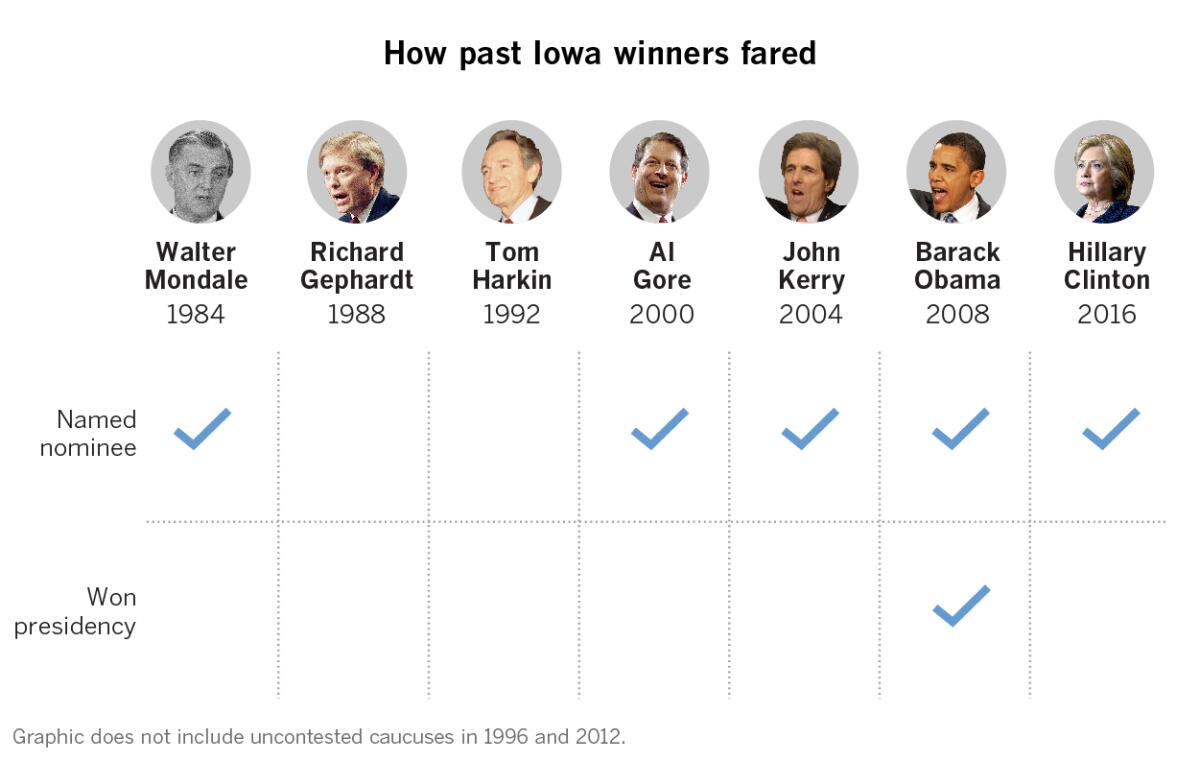

Maybe. But probably not. Among Democrats, the winner of the caucuses has won the nomination in seven out of the 10 contested races since 1972. But only two candidates — Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama — have gone on to win the White House. Among Republicans, the caucus winner has won the nomination in three of eight contested contests, but only won the White House once: George W. Bush in 2000.

The caucuses definitely have had their moments, allowing candidates to prove their viability. Among the top examples is Obama in 2008. His ability to win the caucuses — beating John Edwards and Hillary Clinton in an overwhelmingly white state — helped dispel doubts that the United States could elect a black president.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.