Does L.A. Catholic school have a religious-liberty right to fire a teacher who gets cancer?

- Share via

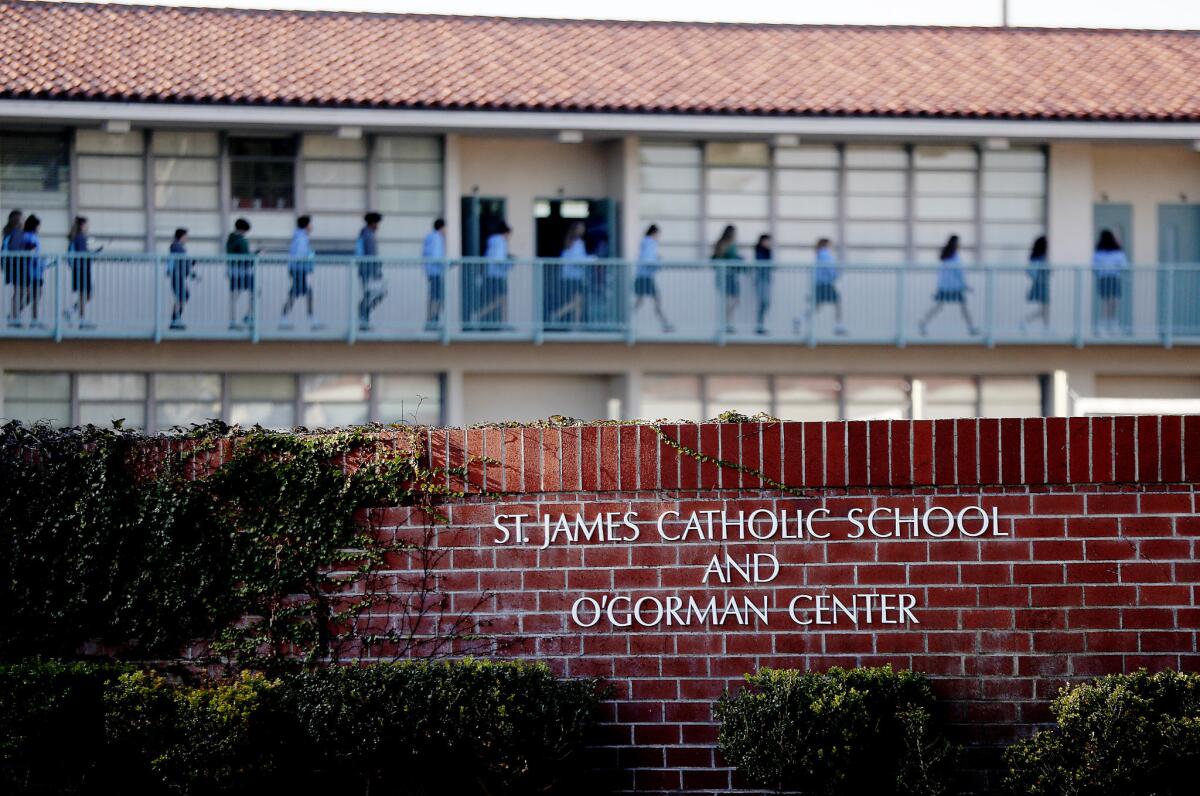

WASHINGTON — Kristen Biel taught fifth grade at St. James, a Catholic school in Torrance, when she told principal Sister Mary Margaret Kreuper she had breast cancer and would need time off for surgery and chemotherapy.

A few weeks later, the principal told her she could not return in the fall of 2014. Kreuper faulted her for a noisy classroom and said it would not be fair to the children to have two teachers that term, as Biel took time off to recover.

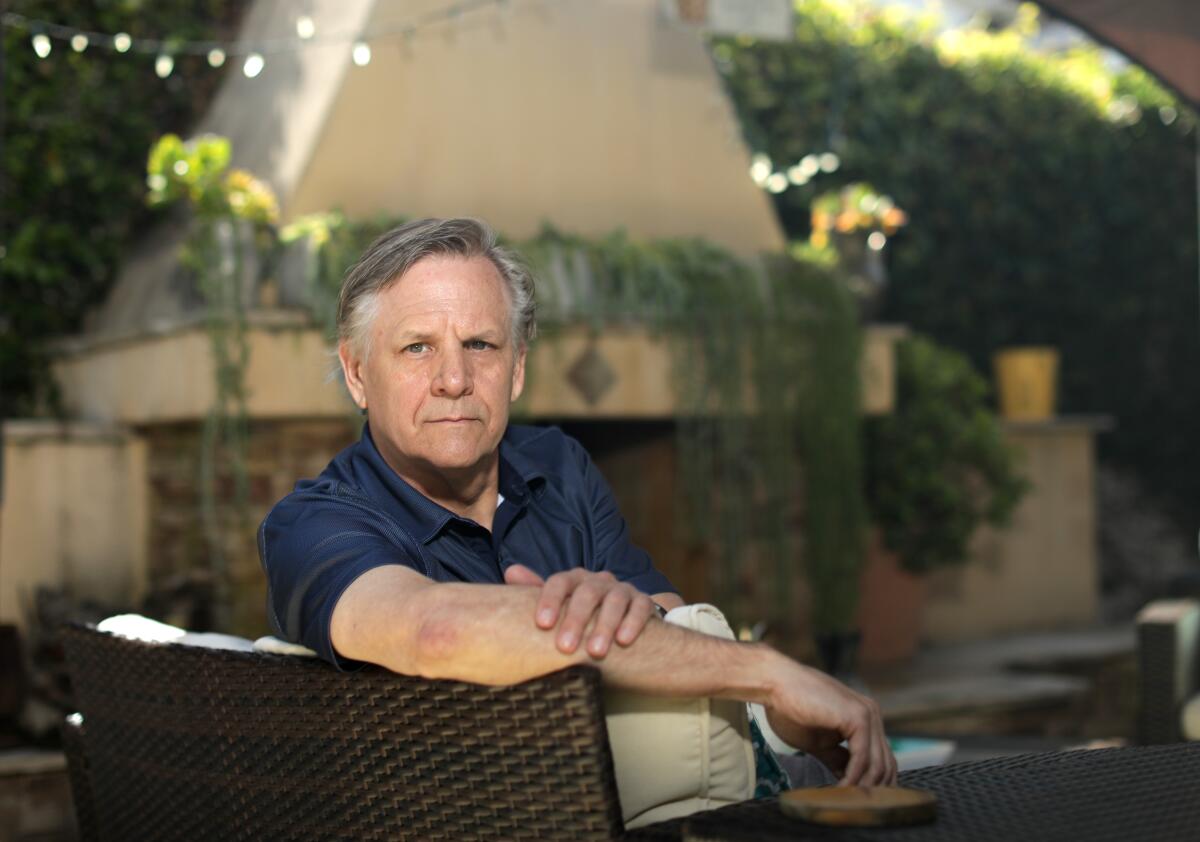

“She came home in tears,” said her husband, Darryl Biel. “She had gotten so many notes from parents about how much she had done for their children. She was so hurt by what happened.”

Kristen Biel filed a federal lawsuit for disability discrimination based on her cancer diagnosis. She died last summer, shortly after the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals cleared her suit to proceed.

On Monday, lawyers for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the Trump administration will urge the Supreme Court to throw out Biel’s suit, and a second similar action from a former teacher in Hermosa Beach, and rule that the so-called “ministerial exception” shields the schools from such legal action.

This exception, long recognized by judges but not written into law, holds that courts should not interfere with the decision of a church or other religious body on whether to hire or retain a minister, priest, rabbi or other spiritual leader. Now the high court will hear oral arguments on whether that exception extends broadly to include tens of thousands of teachers in religious schools, and potentially hundreds of thousands of other employees in church-run hospitals, colleges, charities and child-care centers.

At issue is whether those teachers and other employees at religious institutions should be viewed as “ministers,” allowing religious schools to hire and fire them at will, bypassing anti-discrimination laws that prevent basing such decisions on race, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation or other impermissible factors.

The St. James School has been in the headlines for other reasons. Kreuper, now retired, is one of the so-called gambling nuns, accused by church officials of stealing at least $500,000 from school bank accounts to finance trips to Las Vegas. No charges have been filed, but a criminal investigation is underway, according to Adrian Marquez Alarcon, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese.

The Biel case is the latest in a campaign to expand religious-liberty rights. Last week, the high court weighed the Trump administration’s push to exempt employers who oppose birth control on religious or moral grounds from Obamacare rules requiring most health plans to offer no-cost contraceptives.

On another front, the Supreme Court ruled in 2017 in favor of a Lutheran church in Missouri that had been denied a state grant to improve the playground for its day care center. The state argued its constitution prohibited sending taxpayer money to a church, but Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said that denying a grant to the church, but not similar secular groups, amounted to “odious” discrimination against religion.

The justices are expected to rule soon in a follow-up case from Montana on whether parents who send their children to religious schools have a right to state scholarship aid. In Espinoza vs. Montana, Trump’s lawyers said imposing a “special disability” on students who enroll in church-run schools “violates the free exercise” of religion protected by the 1st Amendment.

The court has also agreed to consider whether the Catholic Social Services has a right to participate in a city’s foster care placement program even though it refuses to work with same-sex couples as required by city law. In Fulton vs. Philadelphia, which will be heard in the fall, lawyers for the Catholic group say that excluding them amounts to unconstitutional discrimination based on religion.

The St. James case focuses on balancing rights in the workplace. Between 1964 and 1990, Congress made it illegal for employers to fire employees or otherwise discriminate against them based on their race, religion, sex, national origin, age or disability, which can include diseases like cancer. Lawmakers recognized a limited exception for churches and other “primarily religious” employers. They may prefer to hire members of their own faith. But otherwise, the anti-discrimination laws extend broadly to employers.

Lawyers for the Catholic schools argue that because Biel’s classroom duties included teaching a religion assignment for 30-40 minutes a day, four days a week, she was like a minister and subject to firing by the the principal for any reason, including her illness.

“You can’t have government decide who teaches the faith,” said Eric C. Rassbach, a lawyer for the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which stepped in to defend the Archdiocese when the case reached the 9th Circuit.

He relies heavily on a 2012 Supreme Court ruling that dismissed a discrimination lawsuit from a “called” teacher at a Lutheran school in Michigan. The Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran school had “lay” teachers, who had no special religious training, as well as a few “called” teachers, who had extra religious training. They carried the title of “minister of religion” and led prayers at school and taught religion.

“We agree that there is a ministerial exception” under the 1st Amendment, Chief Justice Roberts said in a 9-0 ruling in favor of the Lutheran church. “We are reluctant, however, to adopt a rigid formula for deciding when an employee qualifies as a minister.”

That’s the question before the court in St. James vs. Biel and Our Lady of Guadalupe vs. Morrissey-Berru, the second related case.

Since 1999, Agnes Morrissey-Berru had taught fifth- and sixth-graders at Our Lady of Guadalupe in Hermosa Beach. She was in her 60s when a new principal demoted her to part-time and then refused to renew her contract. She sued and alleged she was a victim of age discrimination.

Both Morrissey-Berru and Biel initially lost before federal district judges, but won before the 9th Circuit Court. Because the two teachers did not have special religious training and were not viewed as religious leaders at school, they were not covered by the “ministerial exception,” the appeals court ruled.

The Trump administration joined in the support of the archdiocese and urged the court to adopt a broad rule. “The ministerial exception should apply to any employee who preaches a church’s beliefs, teaches its faith, or carries out its religious mission.” Such a standard could sweep in church-run hospitals, universities, charities and child care centers that say they carry out a religious mission.

Arguing for the former teachers, Stanford law professor Jeffrey Fisher said the court should limit the employer’s legal immunity to those who are “spiritual leaders” at school.

“Lay teachers are not ministers,” he said in his brief to the court. “While a slice of their classroom time involved instruction about the Catholic religion, [the two teachers] performed this duty strictly from workbooks, not as preachers of the faith. And they spent the overwhelming majority of their time teaching secular subjects.”

The high court will not decide whether the teachers were victims of illegal discrimination, only whether they can proceed with their suits and try to prove their claims.

Darryl Biel said he will listen to the audio broadcast of the arguments, which begin at 7 a.m Pacific on Monday. “I’m really disappointed with the archdiocese for what they put her through,” he said, adding that his wife was determined to seek justice. “She made me promise to see this through.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.