The federal agency that enforces campaign finance laws can’t even meet. Why?

- Share via

When President Trump tweeted that the U.S. may need to delay the November election, the longest-serving member on the Federal Election Commission joined the chorus of voices pointing out that he does not have the authority to make that decision.

“No, Mr. President. No,” Ellen Weintraub wrote. “You don’t have the power to move the election. Nor should it be moved. States and localities are asking you and Congress for funds so they can properly run the safe and secure elections all Americans want. Why don’t you work on that?”

Weintraub, a Democrat, holds one of six positions on the FEC, the independent agency tasked with overseeing the country’s campaign finance laws. But the FEC, three months before a presidential election, can’t even call a meeting.

Under normal circumstances, the commission would have at least four members, the minimum required to meet, issue advisory opinions and approve enforcement action. But circumstances at the agency aren’t normal: For most of the last year the FEC has only had three members, rendering it nearly powerless.

It’s unlikely the Senate will confirm a fourth member before the November election — the president’s last nominee waited nearly three years for a Senate vote.

Even if a new commissioner were confirmed, campaign finance reform advocates have lamented for years that the agency has been hampered by structural issues, a lack of resources and partisanship that have weakened its ability to enforce the law and deter illegal election spending. They say the problem has been exacerbated by Republican leaders opposed to limits on campaign spending, who have sought to weaken the agency.

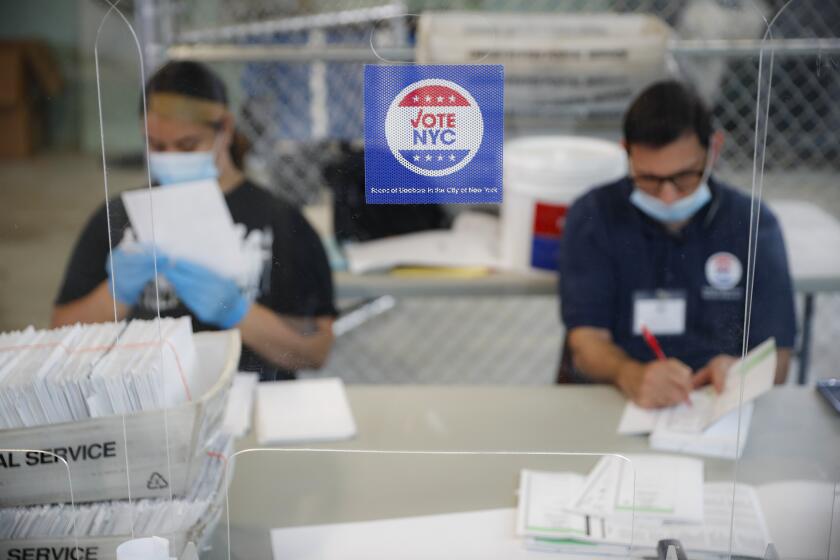

The pandemic has pushed elections system to the brink, with officials in some states fearing a meltdown this fall. Lack of money is a major problem.

Without a strong commission, some have felt free to defy campaign finance laws without fear of punishment, said former Democratic FEC Commissioner Ann Ravel. “They knew that they could flagrantly violate the law and there would be absolutely no consequences, or if there ever was a consequence, that it was going to be so small, that it was essentially a cost of doing business,” she said.

Meanwhile, the backlog of cases continues to grow. The FEC had more than 300 pending cases at the end of March, including 90 in which the five-year statute of limitations was set to expire in the next 18 months, according to a May 2020 memo from the agency’s acting general counsel.

“The agency charged with administering and enforcing the federal campaign laws that will govern the 2020 election remains without the four Commissioners it needs to make most of its major decisions,” Weintraub wrote in December 2019. “It is, to be charitable, less than ideal.”

What does Watergate have to do with the FEC?

The FEC was formed in 1974 after the Watergate scandal to enforce the country’s new election spending laws and the campaign finance abuses of the presidential race two years earlier.

The bipartisan, independent agency was designed to — ideally — investigate potential cases of illegal campaign spending, issue advisory opinions where the law is murky, administer public funding for presidential campaigns and disclose campaign finance data to the public.

The establishing statute calls for six commissioners — no more than three from the same party — who are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate for six-year terms. That structure was intended to prevent one party from taking over the commission, but Democratic commissioners say Republicans have used the structure to block aggressive enforcement, while Republicans say Democrats have attempted to overstep their bounds and stifle free speech.

Feuding on the FEC

The debate played out in letters commissioners sent to House Administration Committee Chair Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) last year after her panel asked what the agency’s biggest hurdle has been in completing its mission,

Weintraub pointed to her Republican colleagues: “For the past 11 years, the Federal Election Commission has been severely challenged from the inside by a group of commissioners who harbor ideological opposition to the very nature of the agency and the law we are charged with enforcing.”

Commissioners Matthew Petersen and Caroline Hunter — Republicans who have since resigned — wrote that the greatest challenge was “the common misperception that adherence to the rule of law and sensitivity to Americans’ 1st Amendment rights reflect hostility towards enforcing the law or, even, towards the Commission itself.”

Why are there still vacancies?

Four commissioners have left the agency since 2017. Ravel left in February 2017, Republican Lee E. Goodman in February 2018 and Petersen in August 2019. Petersen’s departure left the commission without a quorum for nine months, the longest period in its history. The FEC has lacked a quorum only three times since it began operating in 1975: during a six-month period in 2008, from late August 2019 to May 2020, and from July 4, 2020, to the present.

In May 2020, the Senate confirmed Republican James “Trey” Trainor, a Texas elections attorney first nominated by Trump in 2017, briefly restoring the FEC’s powers. But on June 26, Hunter announced she was resigning effective July 3 to work for Stand Together, the nonprofit network funded by the billionaire industrialist Charles Koch, whose political spending helped create a right-wing libertarian movement.

On the day Hunter’s departure was revealed, the president announced his intent to nominate to the commission Allen Dickerson, legal director of the Institute for Free Speech, which supports less aggressive regulation of campaign finance laws.

Neither the White House nor the Senate had announced that the nomination had been sent to the Senate, based on a review of recent nomination announcements. The White House and a representative for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) declined to comment on the record.

What about all those cases?

Without a quorum of four, the commission cannot meet, much less change rules, issue advisory opinions, defend itself in legal matters or make enforcement decisions, according to the Congressional Research Service. And even if there were a quorum, it would take four yes votes to approve any high-level business.

The agency’s backlog continues to grow as new complaints are filed leading up to the November election.

The Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan group founded by former Republican FEC Commissioner Trevor Potter, filed a complaint July 28 alleging that the Trump campaign had laundered $170 million in campaign funds through firms run by his former campaign manager Brad Parscale and campaign lawyers. The complaint alleges that the campaign’s tactics hid the ultimate recipients of the funds, in violation of disclosure laws.

President Trump’s campaign is hiding nearly $170 million in spending from mandatory public disclosure, a government oversight group says.

There’s little chance the FEC would have a ruling by November, even if it were fully staffed.

“It’s not at all uncommon for them to take two to three years, even when there is a full quorum on the commission,” said Brendan Fischer of the Campaign Legal Center. “There are still a number of complaints that we have that are still pending from the 2016 election, and absent the FEC resolving those complaints, we have seen the activity repeated.”

The lack of quorum has also stopped the commission from providing timely advisory opinions in response to questions posed to the agency.

After campaign finance reform groups questioned the legality of former Democratic presidential candidate Michael R. Bloomberg’s decision to transfer $18 million from his suspended campaign to the Democratic National Committee and Andrew Yang’s pledge to give a “freedom dividend” of $12,000 spread out over a year to 10 U.S. families, the candidates could have asked the FEC to weigh in.

“At least with four you could get some agreement on those advisory opinions. And now you cannot,” Ravel said. “Even people of good will aren’t going to know how they should be able to comply with the law.”

What changes do reformers want to see at the FEC?

In a statement after her resignation, Hunter spoke of her “strong belief in the need to protect Americans against unnecessary and overzealous government intrusion.” In her resignation letter, she pointed to the deep ideological divisions between Democratic and Republican commissioners, specifically criticizing Weintraub, whom she clashed with publicly, saying Weintraub “routinely mischaracterizes disagreements among Commissioners about the law as ‘dysfunction,’ rather than a natural consequence of the FEC’s unique structure.”

But while Republicans have defended that structure, Democrats have advocated for fundamental changes.

House Democrats sought to reshape the commission in the campaign finance and ethics reform bill passed last year. The bill would turn the commission into a five-person panel, with no more than two from the same party (leaving the fifth spot open to an independent or third-party option), putting an end to deadlocked votes. A quorum would consist of a majority of members and decisions would be made with a simple majority.

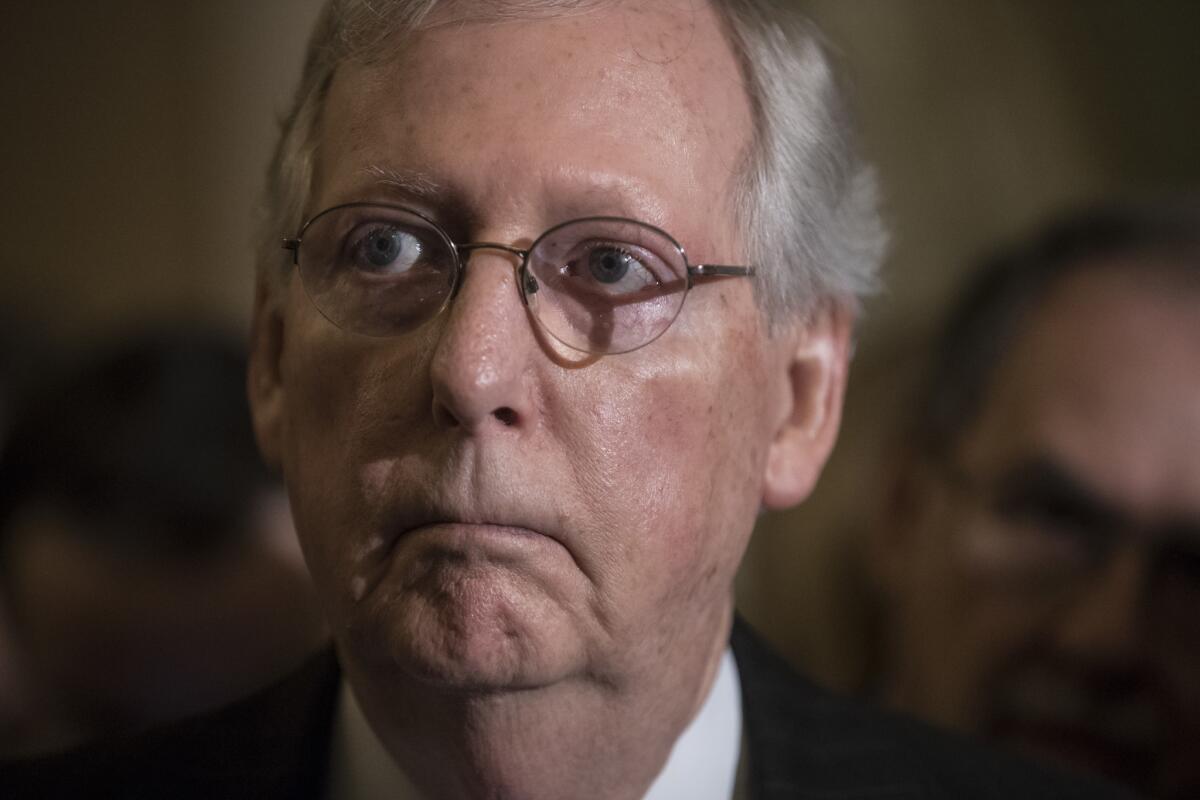

The bill also calls for a panel of experts to nominate new commissioners, whereas now presidents defer to congressional leadership. McConnell, a firm opponent of limiting political spending, has made it clear that he has no plans to bring up the legislation in the Senate.

He has said that the problem with the commission isn’t its bipartisan makeup, but the fact that most of its members are serving long past the ends of their terms. Both Weintraub and independent Steven Walther have stayed on for years past the end of their terms because no one was confirmed to replace them.

“I’d suggest what we actually need to do is have the commission fully functioning as it already exists: totally filled out, with a clean slate of commissioners, all serving on real unexpired terms, to bring new energy, build new relationships and inject some new perspective,” McConnell said at the March 10 Senate Rules Committee hearing on Trainor’s nomination.

Senate Democrats recommended Shana Broussard, a lawyer and executive assistant to Commissioner Walther, for nomination last year, according to multiple reports, but the Trump administration has not acted.

Supporters of campaign finance regulation say McConnell has undermined the agency to prevent aggressive regulation of campaign spending.

“I think he knows at this point that he’s going to have a really hard time deregulating campaign finance laws through Congress,” Fischer said. “But he realized that if he can neuter the FEC, if he can get three ideological opponents of campaign finance on the FEC, he can basically undermine the law from within.”

Fischer said that although it’s “certainly a problem” that the FEC doesn’t have a quorum, it’s more important “that the individuals who are on the FEC should be committed to the mission of the agency and committed to enforcing these important anticorruption laws.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.