Behind closed doors: How Biden’s team weighed the VP candidates

- Share via

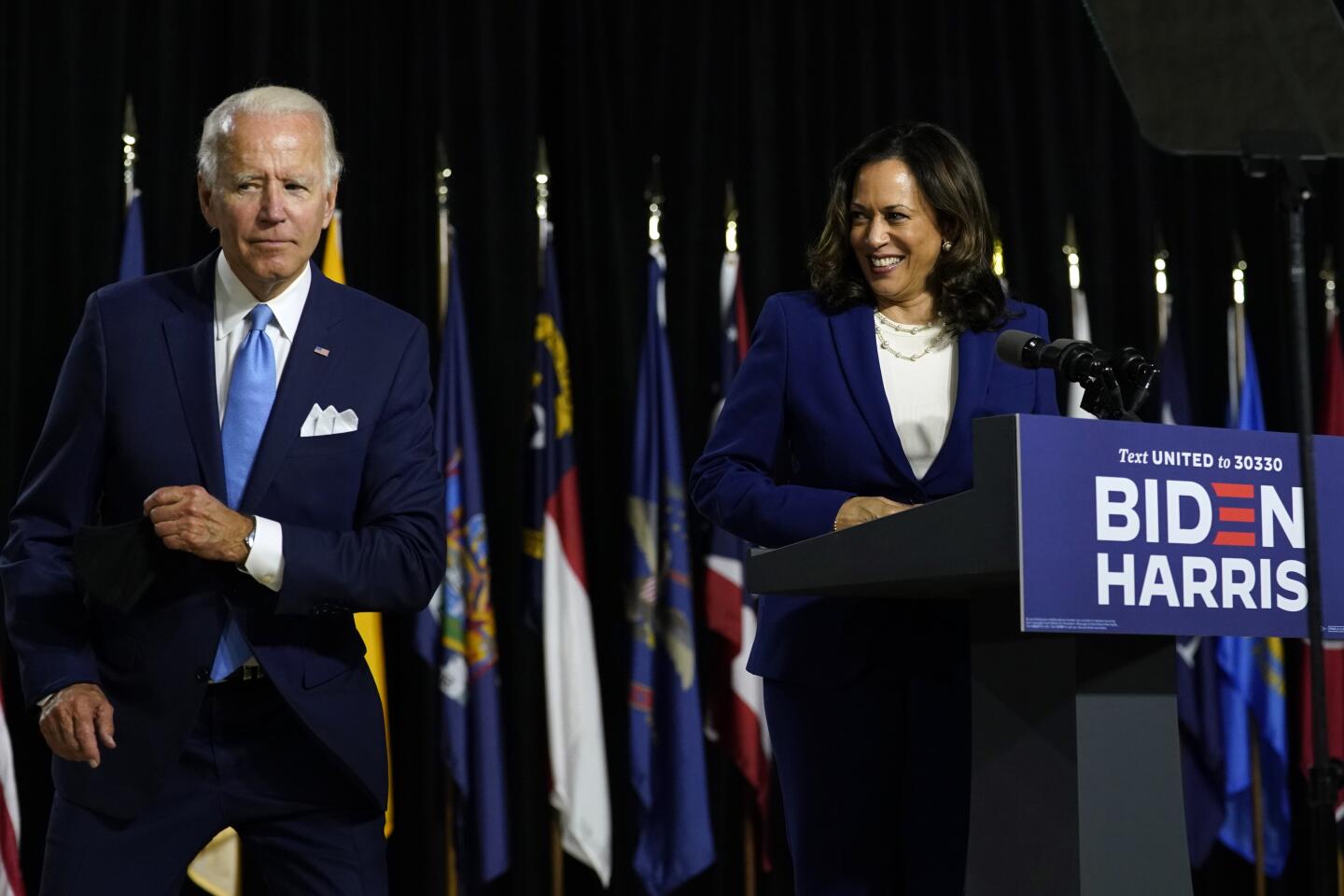

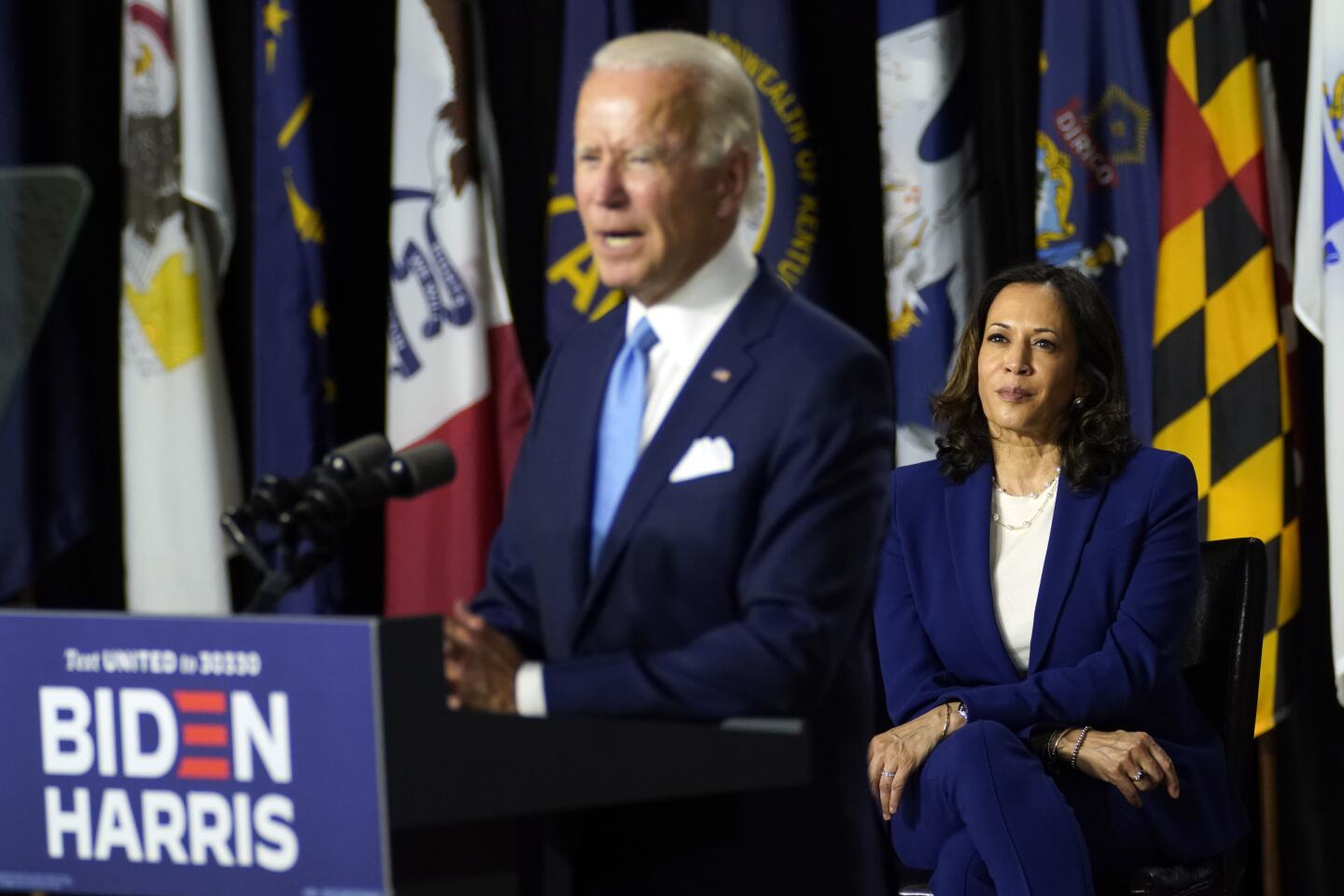

WILMINGTON, Del. — The vetting Kamala Harris endured to earn her spot on Joe Biden’s presidential ticket was like none other in recent history.

It was at once a public audition and highly secretive. It took sharp turns as the nation struggled with a pandemic and erupted in protest following the killing of George Floyd. In the era of Trump, the process even included considering what derogatory nickname the president might give her.

Biden’s vetting committee asked Harris for her guess, but sources familiar with the process wouldn’t say how close she got to “Phony Kamala” — the moniker President Trump quickly bestowed.

Harris emerged from a long list of candidates winnowed over dozens of hours of meetings by a small committee of Biden’s trusted allies, including Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, former Connecticut Sen. Christopher J. Dodd, Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester of Delaware and former Biden counsel Cynthia C. Hogan.

With the pandemic making travel and in-person meetings unsafe, the group resorted to convening over video links, which stoked concerns about hacks and leaks. According to a senior campaign official, the group resolved not to write anything down. “It was all done orally,” the official said.

As the legal team sifted through candidates’ records for potential liabilities, the vetting team focused on “getting to know the essence of who they are,” the official said. Biden’s vetters “understood what kind of people he works well with. They were looking to find out how the people on this list learn, how they think.”

After the protests broke out nationwide, the mix of candidates changed: Black women gained prominence. Earlier contenders who’d made the cut were called back to discuss racial justice.

Harris was always a front-runner. She was ready on Day One, tested in the rigors of a national campaign, a skilled orator. The major hurdle was repairing her relationship with Biden after a bruising primary campaign in which she demanded on the debate stage that he apologize for working years earlier as a senator to limit school integration.

“They had the right heart-to-hearts,” the senior official said. “They came back to a place they always had, of affinity for one another, even a love.”

Meanwhile, media speculation intensified, some of it wildly off-base. Under the radar, two relatively obscure governors made it farther than was known.

Michelle Lujan Grisham of New Mexico drew intense focus after a union leader close to Biden made a big pitch for her. During one online discussion, a committee member held up a Venn diagram showing that she checked more boxes than any of the other candidates. Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo’s appeal was a background that matched Biden’s — raised in a working-class Catholic household, saw her father lose his job, and became a political power in a tiny Eastern state.

Los Angeles Rep. Karen Bass entered the fray amid the Floyd protests. That put Garcetti in the awkward spot of judging two California politicians with whom he has worked closely. Some Harris allies complained that he and Dodd promoted Bass over Harris, but those involved disputed that and said the group didn’t rank candidates.

“He didn’t put his thumb on the scale for anyone,” said a Garcetti confidant.

The lobbying was intense, particularly for Harris. Among her advocates were prominent Californians such as Oakland Rep. Barbara Lee and Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalaki. Perhaps most effective was Ben Crump, the civil rights attorney who represented the Floyd family and others opposing police violence. An adulatory op-ed Crump wrote helped diffuse the campaign’s concern about Harris’ prosecutorial past, a source familiar with the vetting said.

Biden, having been through this process himself 12 years ago, was concerned about the runners-up. “He was very clear there is not going to be one winner and a group of losers,” the campaign official said. Biden personally called each one before his decision became known; some may yet find a prominent place in a Biden administration, should he be elected.

Not everyone escaped unscathed. Bass, a relatively low-profile, uncontroversial lawmaker, found herself under intense media scrutiny after video surfaced of a speech in which she praised Scientologists. Her past affinity for Cuba and its late dictator, Fidel Castro, drew condemnation in Florida, a crucial swing state.

By late July, Harris and Biden were meeting in person. She was one of four who made the trip, dodging media stakeouts and reporters tracking flights in and out of Delaware’s few airports. Others had one-on-one meetings over Zoom with Biden.

His public assurances that there were four Black women in contention, and that he would decide by Aug. 1, confused some of the people involved. The vetters were still sorting through an immense amount of material, including from party activists and interest groups.

“Sometimes people said, ‘You better choose this person or else,’” the official said. Yet Biden “chose the same person he would have chosen whether or not we were in this pandemic, or whether or not we were in the midst of this movement for racial justice.”

Times staff writers Melanie Mason and Janet Hook contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.