Column: Will the 2020 presidential campaign turn out to be the low point in modern political civility?

- Share via

If you’re wondering when American politics hit its low point in civility, I’d nominate Aug. 6, 2020. That was the day when President Trump had this to say about his rival for the presidency, lifelong Catholic Joe Biden: “He’s against God.”

Partisan polarization has been part of American politics for decades, but in 2020 our national fault line expanded into dangerous new territory: demonization and delegitimization.

In his reelection campaign, Trump didn’t merely denounce Biden and other Democrats as misguided; he accused them of being enemies of the nation — and being evil.

“They’re vicious, horrible people,” he said at one campaign rally.

“They hate our country,” he said at another.

That isn’t normal political language in the United States, not even in the heat of an election campaign. And when a president abandons all norms of civility, the problem is bigger than a mere lapse in etiquette; his words and actions encourage others to behave badly, too.

Democracy rests on a principle of mutual tolerance: We may hate our opponents’ ideas, but we accept their legitimacy and their right to compete just as they accept ours.

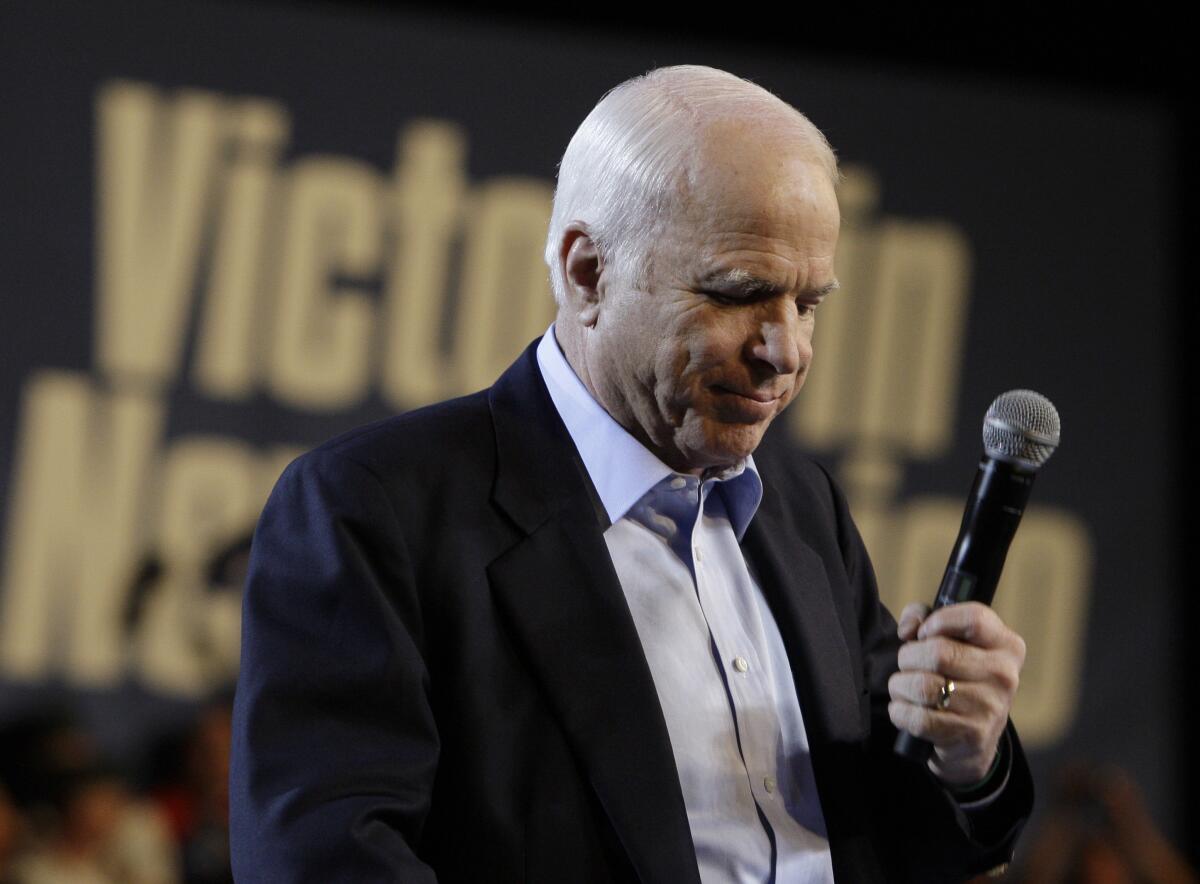

Think, for example, of what Republican presidential nominee John McCain said of Democratic nominee Barack Obama during their 2008 campaign: “He’s a decent family man [and] citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues.” That’s the norm we once expected our politicians to maintain.

Now imagine Trump saying anything close to that.

When protests erupted after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, most presidents would have called for calm and national unity; Trump seized the moment to attack Democratic governors and mayors.

His norm-busting campaign of division extended even to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you take the blue states out … we’re really at a very low level,” he claimed in September. (The assertion was not merely false; it was wildly false.)

Polarizing language has consequences. A Pew Research Center poll in October found that about 9 in 10 voters in both parties said they believed an election victory by the other side would result in “lasting harm” to the country.

That’s a dangerous trend. “When one group views the other as a threat, they’re much more willing to accept undemocratic moves by their side — because they want their guy to stay in power,” political scientist Jennifer McCoy, who studies authoritarian regimes, told me.

The Year in Review

The belief that each party poses an existential threat to the other also makes it more difficult for politicians to negotiate with each other after elections are over — if only because many of their voters loathe the idea of compromising with the other side.

In one of his last acts as president, Trump broke one more political norm, perhaps the most basic of all: the principle that a losing candidate accepts the outcome of an election.

Even after Republican-controlled state legislatures certified Biden’s victory in swing states such as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, he refused to concede.

So, the election resolved only one question: which candidate would be inaugurated Jan. 20. All our other divisions — political, geographical and racial — remain unhealed.

The next four years will tell us whether 2020 will be remembered as the modern era’s low point in American civility, or whether we have further to fall.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.