Democrats aim for paid family leave and aid well beyond Biden’s expected plan

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Congressional Democrats unveiled a far-reaching — and costly — plan for aid to American families on Tuesday, including a guaranteed 12 weeks of family leave for most American workers and permanent extension of help to low- and middle-income families with children.

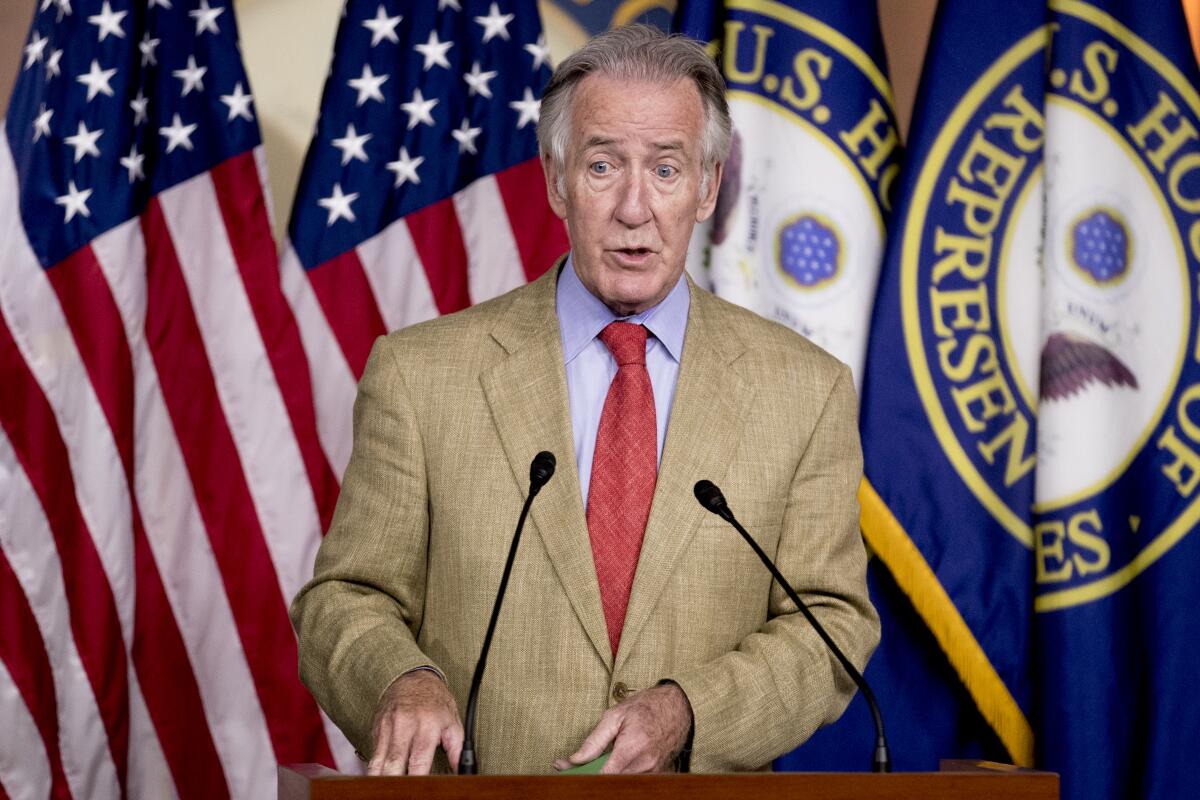

The proposal by the head of the House’s tax-writing committee, Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), would go significantly further than the family assistance plan that President Biden is expected to release Wednesday in a speech to a joint session of Congress.

The move marks the latest step in an intense debate among Democrats about how aggressively to use their narrow congressional majorities to push their top-priority social programs.

It sets down an important marker going into negotiations with the White House and Republicans over the next few months aimed at producing a final package by late summer or early fall. It also could have the effect of making the White House proposal appear as the moderate alternative, providing Biden some cover in the face of Republican attacks on his spending plans.

A key element of Neal’s plan would make permanent the expansion of the child tax credit that Congress adopted for one year as part the $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief bill in March.

The COVID bill turned the tax credit into a near-universal child benefit by making it fully refundable, meaning that families that make too little money to owe taxes will get a refund check from the government. Under the new law, the benefits will be paid monthly, starting as early as July.

That expanded amount could reach an estimated 27 million children who haven’t previously been eligible for the full benefit, lifting several million out of poverty. A single parent with two children working a minimum-wage job could see a roughly 25% increase in income under the plan. The measure could reduce the number of children living in poverty by nearly half, according to a study by the National Academies of Sciences.

The debate now is over how long to extend that program. Although Biden has said he supports making the child allowance permanent, he is expected to propose a five-year extension for now. The cost of the program, roughly $110 billion a year now, with a rising price tag later in the decade, could push out other priorities if the plan has to factor in the cost of a permanent extension, White House officials fear.

Leading Democratic members of Congress, including Neal, however, say they plan to include a permanent extension in this year’s bill.

“The House is going to write the bill, and we will make it permanent,” Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), the chair of the House Appropriations Committee, said at a news conference Tuesday.

Senate supporters of permanently extending the child allowance said at the news conference that they believe they can figure out ways to offset the cost so that it can fit within the confines of a budget bill later this year.

Although a future Congress in five years might vote to extend the program further, “bad things happen in the middle of the night” during such negotiations, said Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio). “We shouldn’t take that chance with our kids.”

Added Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey: “I don’t mind having negotiations over bridges and tunnels and corporate tax cuts,” but children “should not be up for negotiations.”

“The children should come first, then everything else can be subject to the sausage making of D.C.,” he said.

Asked about the congressional comments, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Tuesday that Biden “agrees that the child tax credit has a huge impact on … reducing child poverty.”

“There’s also a cost” involved in extending it, she added, “that is part of the discussion we expect to have with Congress moving forward.”

Neal’s proposal would cost upward of $2 trillion over the next decade; Biden’s plan is expected to pencil out at just over $1.5 trillion, although final details remain in flux. That’s in addition to the roughly $2.2 trillion in additional spending over the next eight years that Biden has proposed for repairing roads and bridges, expanding broadband coverage, upgrading power grids and other infrastructure projects.

Neal’s plan, which incorporates measures offered by other Democratic leaders, has two major pieces in addition to the permanent expansion of the child credit: a new paid family-leave plan and expanded aid for childcare.

In the 2020 campaign, pollsters said Biden was well-known, but not known well. As his presidency nears its 100th day, the blank spots are filling in.

The family leave plan is similar to laws in California and five other states plus the District of Columbia that provide paid leave for the birth or adoption of a child, family health crises and other major events. The benefit would cover at least two-thirds of most workers’ incomes, although top earners would get a lower percentage.

The childcare plan includes a payroll tax credit to boost the pay of workers at childcare centers, a traditionally low-wage industry, and it would fund improvements in such facilities. It would also make childcare more affordable by increasing the tax credit for those expenses.

“These are things I’ve always wanted to do,” Neal, who has served in Congress for more than three decades, said in an interview.

The “grimness” of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused public attention on the need for greater government assistance to working families, he said, adding that Congress should act quickly before the focus dissipates.

“This is the moment, and we’ve got momentum. In legislative life, momentum is everything,” he said.

Biden, in his speech, is expected to offer proposals on each of the three topics covered by the congressional plan. But his bill would spend less on each element.

The president has pledged to cover most of the cost of his spending plan with tax increases on corporations and wealthy individuals. Neal, by contrast, has not outlined how he would pay for his plan, deferring that contentious debate until after agreement is reached among Democrats on the spending side.

“There’s a rhythm to legislating,” he said in the interview.

Congressional aides who were not authorized to discuss the plan on the record said House leaders expect the eventual bill to include taxes to offset some of the new benefits.

Many of the Democratic proposals are popular with voters — a newly released Monmouth University poll on Monday, for example, found Americans by 64% to 34% support “a large spending plan” on healthcare, childcare, paid leave and other domestic spending. But such proposals have stalled in the past because of their price tags.

Democrats have only a few-vote margin in the House and a 50-50 split in the Senate, so they need near unanimity among their members to pass the legislation, assuming that most if not all Republicans will be opposed.

Neal said he hoped for Republican support, noting that some GOP leaders have backed proposals for family leave and other benefits in the past. But he made clear that Democrats were prepared to move ahead on their own, taking advantage of the same budget procedures they used to pass the COVID-19 relief bill without GOP support.

Although some Republicans have supported increased spending on infrastructure needs and increased support for families, there’s strong opposition in the party to any bill that includes a tax increase.

White House economic advisor Brian Deese on Monday defended one of the tax increases that Biden plans to propose — an increase in the capital gains tax rate for people earning more than $1 million a year. The hike would largely eliminate the current break under which income from investments gets taxed at a significantly lower rate than income from work.

The tax hike would hit only the highest-income three-tenths of a percent of American households, Deese told reporters, yet would still generate tens of billions of dollars that could finance “really high-return investments” in “early childhood and in our children.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.