Secretary of State Blinken in Central America to target corruption, immigration

- Share via

SAN JOSE, Costa Rica — In search of trustworthy partners, the Biden administration dispatched its top diplomat to Costa Rica on Tuesday to take Central American officials to task on corruption in their countries and to examine how they can more efficiently block “irregular” migration to the U.S.

He could be facing a tough crowd. U.S. relations with the governments of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, in particular, are badly strained, complicating President Biden’s plan to use $4 billion over the next four years to boost democratic reforms and improve the economies in those three so-called Northern Triangle nations — the source of most migrants attempting to enter the U.S. illegally.

Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, arriving here on his first official trip to Latin America, held talks with the president of Costa Rica and most of that nation’s Cabinet, and was to meet with other Central American counterparts later Tuesday night, including a sidebar session with the representatives of the Northern Triangle countries.

“What we hope and expect to hear from our partners are commitments to address all the issues” that drive illegal immigration, such as an erosion in democracy, poor security, poverty and corruption, Blinken said in a news conference at the Casa Presidencial in San Jose, the capital.

“We’re in many of these challenges together,” he said. “What we’re seeing in too many places around the world, including this region, is backsliding from those basic principles” of democracy, human rights and rule of law.

Blinken is attending an annual meeting of the foreign ministers of the eight-member Central American Integration System, an economic and political association of all Central American countries plus the Dominican Republic.

Administration officials say they have already made clear to the Central American presidents that very little of the $4 billion will go to the central governments but instead will be channeled through nongovernmental organizations and other private entities.

Biden will condition billions of dollars in U.S. aid to Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala to push for reform. Will it work?

To underscore that warning, the U.S. Agency for International Development last week announced that it was diverting all aid it gives El Salvador from the government to “civil society” groups that monitor human rights and fight corruption. (USAID did not say how much money was involved.)

The move came after Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele fired the country’s attorney general and Supreme Court magistrates and then ignored entreaties from Washington and elsewhere to reconsider what was widely seen as an illegal power grab.

“We recognize that in some cases we don’t have perfect development partners,” said Mark Feierstein, special advisor at USAID, “but we’re confident that we can identify in Central America ... reformers within government ... [and] civil society actors who can hold their governments accountable.”

Relations with Bukele have been especially tense. He refused in recent months to receive Biden’s visiting envoy in charge of the Northern Triangle, Ricardo Zúñiga; he eventually relented, then appeared to be stunned by the scolding he received, officials said. He dug in afterward, saying the firings were “irreversible.”

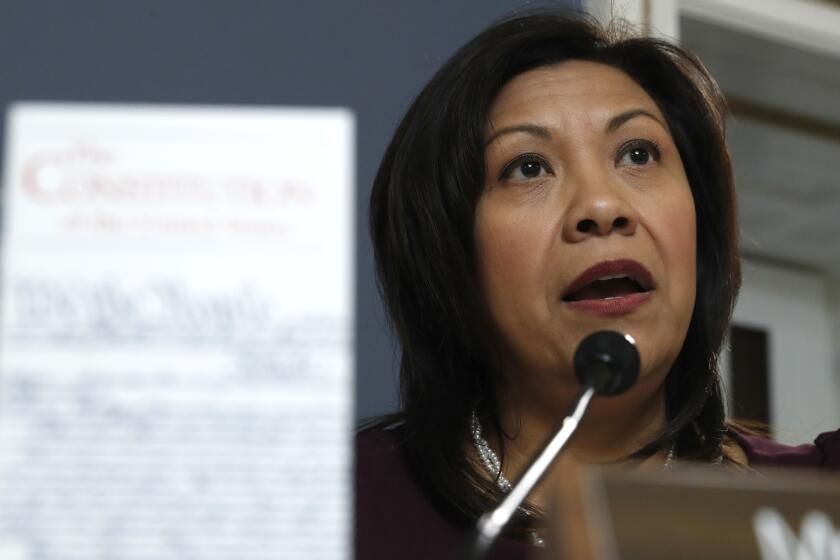

California’s Norma Torres fled Guatemala at 5. Now the only Congress member from Central America says the immigration debate is ‘very, very personal.’

The State Department announced last week that it was returning a former U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, Jean Manes, to the country as charge d’affaires. Officials said the situation was too delicate — and the potential for more abuses by Bukele too great — to wait for confirmation of an ambassador, which could take several months. Manes is considered a diplomat who can get Bukele’s ear.

The Biden administration is concerned about what it sees as similar erosions of democracy in Guatemala, where President Alejandro Giammattei has sought to undercut the courts, and in Honduras, which has an especially difficult problem. Its president, the staunch Trump ally Juan Orlando Hernandez, is under federal investigation in the U.S. on drug-trafficking allegations. Administration officials have said privately they will shun him.

Meeting with the foreign ministers of those countries might yield better results as Blinken hopes to enlist their cooperation on immigration and hear plans for reforms at home. Blinken scheduled one-on-one encounters with the foreign ministers of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. In addition to the Costa Rican president and foreign minister, Carlos Alvarado Quesada and Rodolfo Solano, he will meet with Mexican Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard, who is attending as an observer.

Dealings with Nicaragua, which was also present at the summit, could become a point of contention. No U.S. administration has had a good relationship with Managua for years, ever since President Daniel Ortega began cracking down on the opposition and news media and staying in power through suspicious elections.

Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega has carried out a war on the press, jailing journalists and closing news outlets. In a blow to the storied La Prensa newspaper, he barred delivery of newsprint and ink.

For the Central Americans, the pressing issue is the COVID-19 pandemic. They are hoping to be near the top of the list if and when the U.S. starts giving out vaccines overseas. Costa Rica has seen its worst spate of infections and deaths in recent weeks.

Blinken announced that procedures for the U.S. to distribute 80 million doses to other countries should be finalized within the next two weeks, but he did not say who would get them. It will be based on need and an effort to counter “inequity,” he said.

China, on its march to make inroads everywhere, including Latin America, has been offering vaccines to Central American countries, notably El Salvador, where Bukele has turned his country’s diplomacy closer to Beijing after years of recognizing Taiwan.

Alvarado, asked if Costa Rica would turn to China for vaccines despite concerns about conditions Beijing reportedly puts on them, said any decision to accept vaccine doses would be based on his country’s “dignity,” with “no strings attached.”

Blinken’s trip to Central America will be followed by the first official visit by Vice President Kamala Harris to the region. Harris, whom Biden put in charge of dealings with the Northern Triangle states to combat the “root causes” of immigration, plans to visit Guatemala and Mexico next week.

Harris announced last week that 12 major corporations, including Microsoft and Nestle’s Nespresso, have agreed to invest in Central America. She has said the private investment is a key component of the administration’s plan to shore up economies and employment opportunities.

“To maximize the potential of our work, it has to be through collaboration, through public-private partnerships,” Harris said at a “Call to Action” meeting with the business executives.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.