House sets deadline for EPA to limit toxic man-made chemicals in drinking water

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The House on Wednesday approved a bill setting deadlines for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to implement drinking water regulations for so-called forever chemicals.

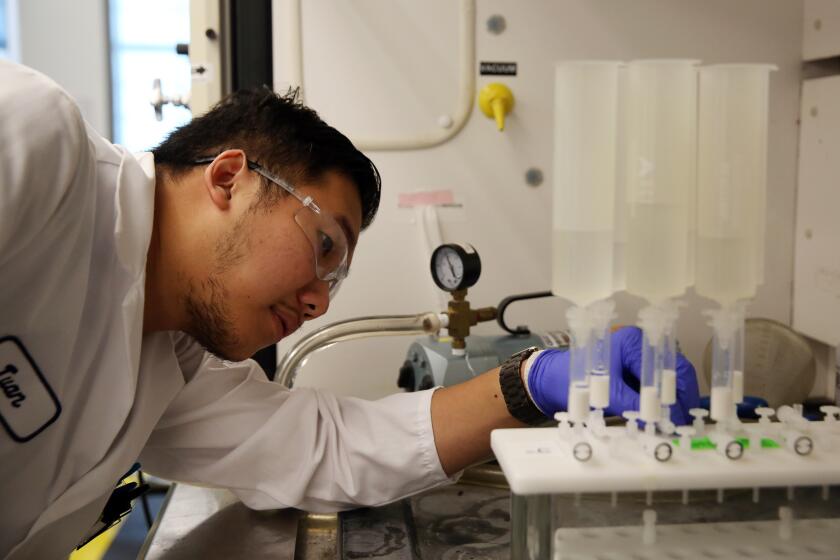

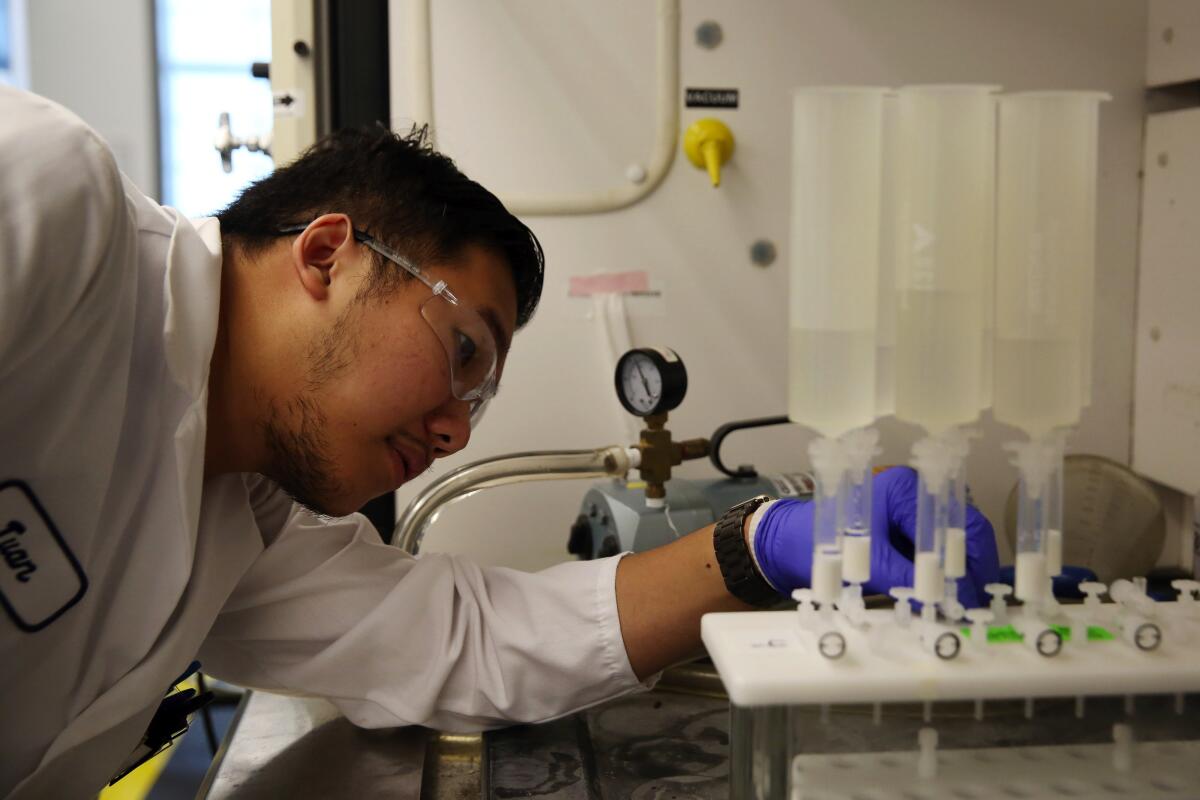

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly called PFAS, are widely used, man-made compounds that are found in manufacturing and consumer products like Scotchguard, flame-resistant materials, nonstick cooking surfaces and firefighting foam used on military bases since the 1940s. They have been found in water wells throughout California and thousands of water sources across the country.

The bill approved Wednesday by a vote of 241 to 182 orders the EPA to designate two PFAS compounds as hazardous air and water pollutants, and set drinking water regulations for their use within two years of the bill becoming law. For years the agency has only established a non-enforceable health advisory level on the compounds in drinking water.

It also gives the EPA four years to set regulations for the discharge of the chemicals in industrial runoff and wastewater, and gives the agency five years to set standards for the use of the thousands of other PFAS compounds.

The bill requires cleanup of PFAS-contaminated sites and reimburses local water agencies for their efforts to reduce the amount of PFAS in drinking water.

The compounds don’t break down in nature and build up the human body. A number of studies and investigations have tied the two compounds that would be designated as hazardous pollutants to cancer and other serious illnesses in recent years.

Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) said the chemical industry has known about the health effects of the compounds for years, but government has been slow to respond and set meaningful standards.

“We don’t even have labeling of PFAS ingredients to allow consumers to protect themselves,” Pallone said. “We can’t delay any longer.”

Nearly 300 drinking water wells and other water sources in California have been found to have traces of man-made chemicals linked to cancer.

Republicans say the bill is too broad and will essentially ban compounds that do have beneficial uses, including as coating on contact lenses and on law enforcement and medical safety gear. They say the bill set unrealistic deadlines to examine a broad group of chemicals that is not clearly defined.

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) called the bill heavy-handed, unscientific and a “de facto ban on 9,252 chemicals.”

“It creates a hostile environment for the manufacture and use of PFAS,” that threatens the viability of the industries that rely on them, she said.

Similar legislation passed the House in January 2020 with bipartisan support, but stalled in the Senate. Supporters hope increased public awareness of the compounds, including the 2019 film “Dark Waters” starring actor and environmental activist Mark Ruffalo, will help it gain support among senators.

The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee held a hearing on the compounds in late June, but did not consider legislation.

The White House has announced that President Biden would sign the bill if it reaches his desk.

Toxic chemicals linked to cancer have been found in dozens of California water systems. Here are some often-asked questions residents have about how to limit their exposure and reduce the level of PFAS in their tap water.

Groups that have pushed for regulations praised the vote as a necessary first step in cleaning up a problem government agencies have known about for decades. The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit advocacy group, estimates that 200 million Americans in thousands of communities are consuming PFAS in their drinking water.

“The PFAS Action Act will set much needed deadlines to ensure that the EPA will take the necessary steps to reduce PFAS releases into our air, land and water, to filter PFAS out of tap water and to clean up legacy PFAS pollution, especially near Department of Defense facilities,” said Scott Faber, the group’s senior vice president for government affairs, in a statement.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.