As L.A. fights port gridlock, U.S. and global leaders pledge to curb shipping emissions

- Share via

The United States, Britain and 17 other countries committed at the United Nations global climate summit Wednesday to curb emissions from the shipping industry by creating zero-emission shipping routes, a move that comes amid growing concern over shoreline air pollution from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

The agreement, called the Clydebank Declaration, says countries will work together to invest in clean energy infrastructure at ports at both ends of major trade routes, establishing at least six “green corridors” by the middle of the decade, which will eventually make it possible to transition ships away from fossil fuels toward cleaner sources of power. If these changes are enacted, governments could require that only emissions-free ships travel from Shanghai to Los Angeles, for example, or from Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, to New York. The initiative is part of an effort announced last week to reduce the maritime sector’s emissions to zero by 2050.

The other countries that signed the pledge at the summit in Scotland are Denmark, Japan, Canada, Australia, Germany, France, Chile, Costa Rice, Belgium, Fiji, Finland, Ireland, Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden.

Globally, the shipping industry is a major emitter of planet-warming greenhouse gases, largely because one of the dirtiest kinds of diesel fuel powers most of its ships. It’s a fuel with a much higher carbon content than the diesel used in cars. Cargo ships collectively spew an average of 1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year, about as much as all U.S. coal-fired power plants combined.

Calling the declaration “a big step forward,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said Wednesday that the U.S. would help lead the effort to limit the industry’s environmental impact.

“In shipping, in particular, there’s a paradox. On one hand, pound for pound, it is typically the least carbon-intensive means of moving goods,” he said. “And yet there is so much of it, consuming so much fuel, that it represents an enormous source of emissions.”

The announcement comes as the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, the busiest in the U.S., face increased scrutiny over cargo ship logjams and worsening air pollution.

When cargo ships burn fuel, they emit more than carbon dioxide, belching a combination of smog-forming pollutants, including ozone, nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, that has been linked to an increase in deaths.

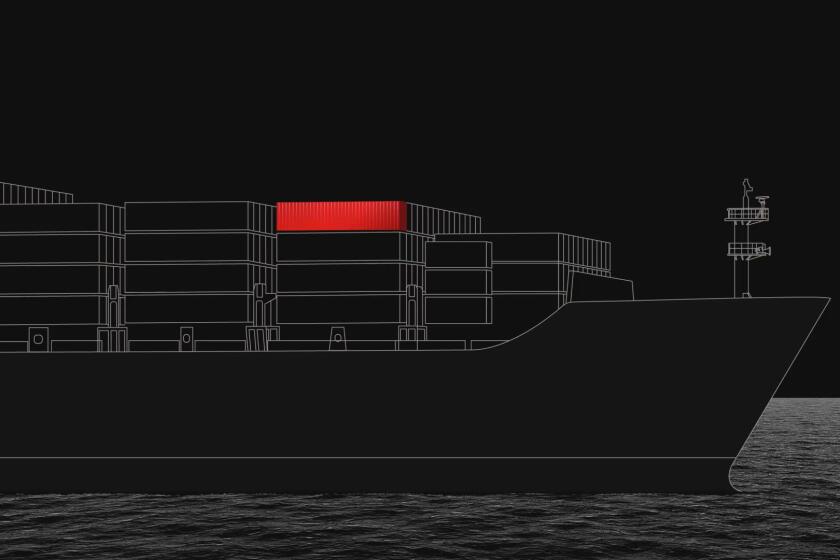

Amid a global supply chain snarl that has persisted for months, dozens of cargo ships have been idling off the coast of Southern California while they wait to dock, sometimes for several weeks. According to the Marine Exchange of Southern California, 103 ships bound for L.A. and Long Beach were sitting at anchor Tuesday, roughly the same number as the week before. During normal times, it’s typical for one ship to be waiting — or none at all.

A global supply chain breakdown has resulted in gridlock at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and beyond.

The traffic jam has mostly gotten attention for the resulting shortages and higher costs that could affect holiday shopping. But environmental advocates are far more worried about the health effects for people living near the ports in Wilmington, San Pedro and Long Beach.

Air quality data for 2020 released by the Port of L.A. show that pollution increased sharply beginning last October, as the number of ships waiting to unload began to grow. Similar data for this year are not yet available.

“This just makes what was an already bad situation worse from an air pollution perspective,” said Adrian Martinez, an attorney for the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice, which has been pressing local air quality regulators to intervene. “It’s a one-two punch for our region, and it doesn’t seem like the public health crisis is getting central attention. The only crisis is the inability to move cargo.”

By 2023, ocean-going ships are expected to surpass heavy-duty diesel trucks to become Southern California’s largest source of smog-forming nitrogen oxide pollution, according to projections by the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

Worldwide, greenhouse gas emissions from the shipping industry are expected to double by 2050. The threat of this increase has put new pressure on the U.N. body responsible for regulating shipping to adopt more ambitious climate targets that align with the commitments countries made to cut emissions under the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

But there have been few signs of that. The organization, known as the International Maritime Organization, has repeatedly delayed regulations to limit emissions in recent years.

A final determination for the cause of the spill may take months, but Coast Guard investigators have come up with no other explanation than anchor drag, federal sources said.

At the heart of what’s made the shipping industry difficult to reform are many of the same problems countries face with electrifying cars and trucks. The technology exists to switch ships from diesel fuel to cleaner energy sources such as hydrogen, green ammonia and batteries, but these fuels aren’t available at the scale needed.

Although a group of large companies, including Amazon and Ikea, committed last month to using zero-emissions ships by 2040, it’s currently not possible for such ships to travel along major routes, as most ports aren’t equipped to refuel them.

In response to Americans’ growing frustration with the disrupted supply chain, President Biden announced last month that the L.A. port would stay open “24 hours a day, seven days a week” to help address the backlog. Major retailers agreed to clear their cargo from the ports more quickly, freeing up space for more shipping containers. A similar plan was already underway at the Long Beach port.

Chris Cannon, chief sustainability officer for the L.A. port, said it is too soon to know whether the port’s extended hours have succeeded in reducing the amount of time ships spend waiting to dock.

The port is still grappling with huge stacks of shipping containers and is looking at new locations away from the terminal where they can be moved so that arriving ships can be unloaded faster.

Ed Avol, a professor at USC’s Keck School of Medicine, said it’s difficult to predict how air pollution from the idling cargo ships will affect residents along the coast.

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

“There’s no direct line we can draw to say, ‘If you get exposed to this kind of concentration, you will get this outcome,’” Avol said. “But we know from lots of research there are associations between increased exposure and short- and long-term health impacts.”

For residents living near the ports who already suffer from asthma and other respiratory or cardiac problems, a months-long increase in air pollution could “push them over the edge,” Avol said.

Under a plan adopted by the L.A. and Long Beach harbor commissioners in 2017, the port complex is supposed to be transformed into an emissions-free facility by 2035. In their first major step to reach this goal, the ports voted last year to impose a roughly $20 fee on shipping containers that would be used to help trucking companies buy less-polluting vehicles.

But when the pandemic began, the ports delayed the fee. Under a recently announced plan, they won’t begin collecting it until April.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.