Harry Reid dealt first blow to filibuster, leaving Democrats to decide whether to kill it

- Share via

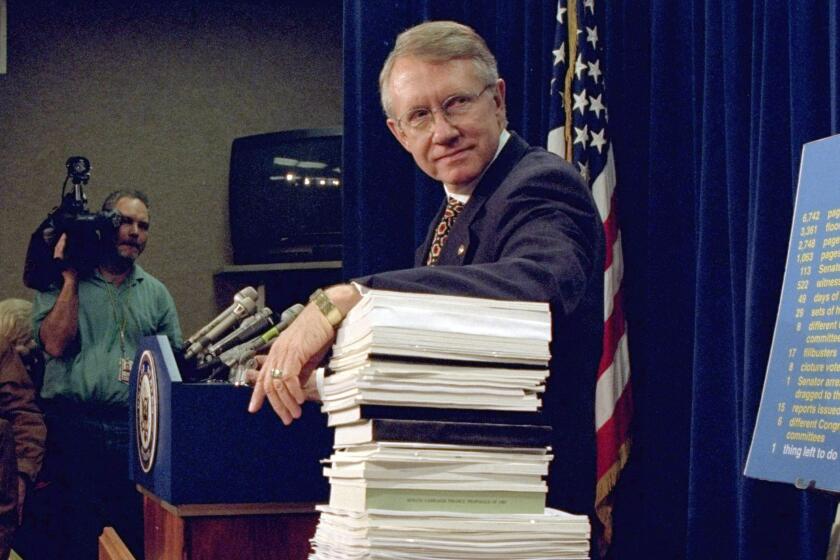

Harry Reid, the pugnacious Nevada Democrat and former Senate majority leader who died Tuesday at age 82, never regretted having gone nuclear.

In 2013, Reid ended the filibuster — the rule that requires 60 votes to prevent a lone senator from speaking at length to block approval — for executive branch and judicial nominees other than those for the Supreme Court. It was among his most consequential decisions as majority leader and allowed President Obama to appoint more judges to key posts than in any other two-year stretch in his presidency. It also opened Reid up to criticism that he accelerated the chamber’s evolution into a partisan battlefield.

The former Senate majority leader helped make Nevada a Democratic state and urged Barack Obama to run for president.

As news of Reid’s death spread Tuesday, many Democrats praised his decision to deploy the “nuclear option” — so called because opponents said ending the filibuster would badly damage the Senate — but they acknowledged it may not have gone far enough.

That has left Democrats weighing whether to finish what Reid started — by nuking the longtime Senate rule for legislation as well as they seek to pass what they say is a crucial voting rights bill.

Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), who since last year has been signaling openness to ending the filibuster altogether, said in a letter to colleagues last week that the Senate would consider “changes to any rules which prevent us from debating and reaching final conclusion on important legislation” if Republicans use the rule to block voting rights legislation.

Reid “saw what was happening to the Senate,” Schumer told MSNBC on Tuesday night. “He was a strong advocate of changing the rules in the Senate, which I hope we carry forward in the next few weeks.”

Such a change is hardly guaranteed: It would require all 48 Democrats and 2 independents to vote to kill the rule, with Vice President Kamala Harris breaking a likely tie with the Senate’s 50 Republicans. At least two centrist Democrats — Sens. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona — oppose the move. That doesn’t mean Democratic leaders are not willing to try to jettison a rule that has existed in its modern form since 1917.

If lawmakers scrap the filibuster, it could result in a seismic shift for the Senate, a chamber that has many members who pride themselves on upholding tradition and building consensus to pass legislation. It would likely mark the formal end to the era of bipartisan deal making.

Reid had predicted the filibuster would ultimately be killed off, and in September told his party in an op-ed to “act with the urgency that this moment demands and abolish the filibuster once and for all.”

“The sanctity of the Senate is not the filibuster,” he wrote in a guest column for the Las Vegas Sun. “The sanctity of the Senate — in government as a whole — is the power it holds to better the lives of and protect the rights of the American people. We need to get the Senate working again.”

Politicians on both sides of the aisle remember former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid as a skilled dealmaker who was both strong and compassionate.

Democrats are facing a dynamic that’s similar to their situation in 2013 — with a Democratic president and control of the Senate by a small margin. Their chief nemesis is also the same: Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.).

Reid acted that year because Democrats were deeply frustrated by Republicans’ use of the filibuster to stall and torpedo Obama’s nominations for key judicial posts.

“I was around when Sen. McConnell famously was quoted as saying he wanted to make President Obama a one-term president. And to give credit for consistency, that’s what he’s trying to do here with President Biden,” said Jim Manley, a Democratic strategist who spent six years working for Reid in the Senate.

“The president’s an institutionalist, just like Sen. Reid was — but if you look at it objectively, something’s got to give,” Manley added.

The tables turned on Democrats in 2017, when Republican President Trump took office. McConnell discarded the filibuster for approving Supreme Court justices after refusing for months to consider Obama’s last nominee to the high court. Trump ultimately put three justices on the court, and also placed more than 230 judges onto district and appellate courts.

Those who support the filibuster say it was intended to give the minority party a voice, particularly on controversial and wide-ranging legislation, and to force the majority to build broad consensus. They have also noted that Democrats will not always be in the majority and may pay a heavy price for eliminating the rule by making it easier for Republicans to pass their own controversial bills and undo signature legislative accomplishments of the last few decades.

Opponents of the filibuster say the rule is a relic that gives the minority outsized control of the agenda in Congress, and that Republicans have abused that power.

Democrats have pointed out that Republicans began to increasingly use the tactic after losing control of the Senate in 2006, and again at the start of Obama’s second term in 2013.

Calls on the left to end the legislative filibuster have increased in recent years. Obama, speaking at the funeral of Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) in 2020, called the filibuster a “Jim Crow relic” and said it should be eliminated if necessary to pass voting rights legislation.

Biden, who spent 36 years in the Senate before serving two terms as Obama’s vice president, has long supported the filibuster, saying getting rid of it would “throw the entire Congress into chaos and nothing will get done.”

But as Democrats have become increasingly concerned this year with Republican-controlled states passing laws restricting voting access, the president‘s views have evolved. Last week, he told ABC News that he would support a filibuster exception for voting rights legislation.

Carving out exceptions, opponents said, would only hasten the filibuster’s ultimate demise.

“It opens Pandora’s box,” said David Winston, a Republican strategist and pollster. “Once you open the door for a particular type of legislation, you potentially open the door for all of it.”

As Reid wrote in September, he would not consider that such a bad outcome.

“How could Washington be any more dysfunctional?” his former aide Rebecca Kirszner Katz said in an email. Katz is a co-founder of the Battle Born Collective, a group that helps advance progressive policies.

“Harry Reid was not quite a progressive, but he was a realist,” she wrote. “He knew what was fair. And the filibuster ain’t it.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.