Biden’s vow to put a Black woman on the Supreme Court stirs mixed emotions among Black lawyers and judges

- Share via

As President Biden prepares to deliver on his promise to make history by nominating the first Black woman to the U.S. Supreme Court, Black Americans in the legal profession say they feel conflicting emotions: vindication and pride, exasperation and dread.

While they appreciate Biden’s determination as he vets candidates, they worry about his overt use of race as a prerequisite at such a hyperpartisan time. Black Americans already find themselves having to defend against accusations that they’re not as skilled, intelligent or prepared as their fellow citizens.

“My initial reaction was probably like most Black folks: It’s about time,” says Merle Vaughn, an attorney and recruiter in Los Angeles who specializes in helping big firms hire lawyers of color. “He’s keeping his promise to Black women because Black women put him in the White House.

“My second reaction is: I can’t believe we’re still seeing headlines that say ‘first Black this’ and ‘first Black that’ — that to me is so old,” says Vaughn, 62. “What’s sad about it is we just can’t be seen as people.”

For South Carolina lawmaker Todd Rutherford, an attorney who serves as the Democratic minority leader of the state House, his happiness with Biden’s goal comes tinged with frustration.

“Saying that [the nominee will be a Black woman] makes it look like white people don’t have a chance — and white people are a little sensitive about that,” says Rutherford, a friend of J. Michelle Childs, a U.S. District Court judge in South Carolina who is reported to be on Biden’s list of candidates for the nomination.

MY COUNTRY

As a Black man in America, I’ve always struggled to embrace a country that promotes the ideals of justice and equality but never fully owns up to its dark history of bigotry, inequality and injustice.

Now, more than any time in recent history, the nation seems divided over this enduring contradiction as we confront the distance between aspiration and reality. Join me as I explore the things that bind us, make sense of the things that tear us apart and search for signs of healing. This is one in a series we’re calling “My Country.”

“You almost wish that the president had said, ‘I’m going to pick the most qualified person,’ and then nominated an African American woman,” says Rutherford, 51. “Without intending to do so, he created the framework for affirmative action that upsets a lot of Americans.”

The cries of “reverse discrimination” that rang out on cable shows and social media in response to Biden’s pledge sounded all too familiar to Vaughn and Rutherford. They know some Americans can’t get past the notion that if a Black person succeeds, it must be because a more qualified white person was passed over.

Biden’s promise puts the contenders, who also include California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger and U.S. Appeals Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, in the uncomfortable position of being doubted despite their stellar careers, Rutherford says.

The questions over the contenders’ fitness sting on a personal level, he says, because he has seen for himself how formidable Childs can be on the bench.

“I’ve been there in front of her in the courtroom, and she is by far the most qualified person that Joe Biden could pick — period,” Rutherford says. “Notice I didn’t say ‘most qualified African American.’”

A Yahoo News/YouGov poll found that while a majority agreed that the top contenders are qualified, only a third of respondents expressed confidence that Biden would choose “the right kind of person” to fill the vacancy.

It’s also hard for Rutherford to feel completely at ease with the president’s approach when Americans are ambivalent at best about the idea that the government and businesses should rectify hundreds of years of enslavement and racism by giving special consideration to the inequities that resulted from that oppression.

During the Jim Crow era, many Southern communities banned Black residents from even serving on juries, and aspiring Black college students had to file lawsuits, protest and face racist violence to gain admittance to public law schools.

Yet even today, only 23% of Americans agree that nominating a Black woman to the Supreme Court is “very important,” according to the same Yahoo News/YouGov poll of 1,628 adults, conducted earlier this month.

The Democrats’ fragile Senate majority, frustrating as it is for passing legislation, is crucial and powerful for confirming federal judges.

Vaughn finds it “ridiculous” that in 2022, Black Americans still have to convince some of their fellow citizens of the need for government institutions to reflect the diversity of the nation they’re sworn to serve, the Supreme Court included.

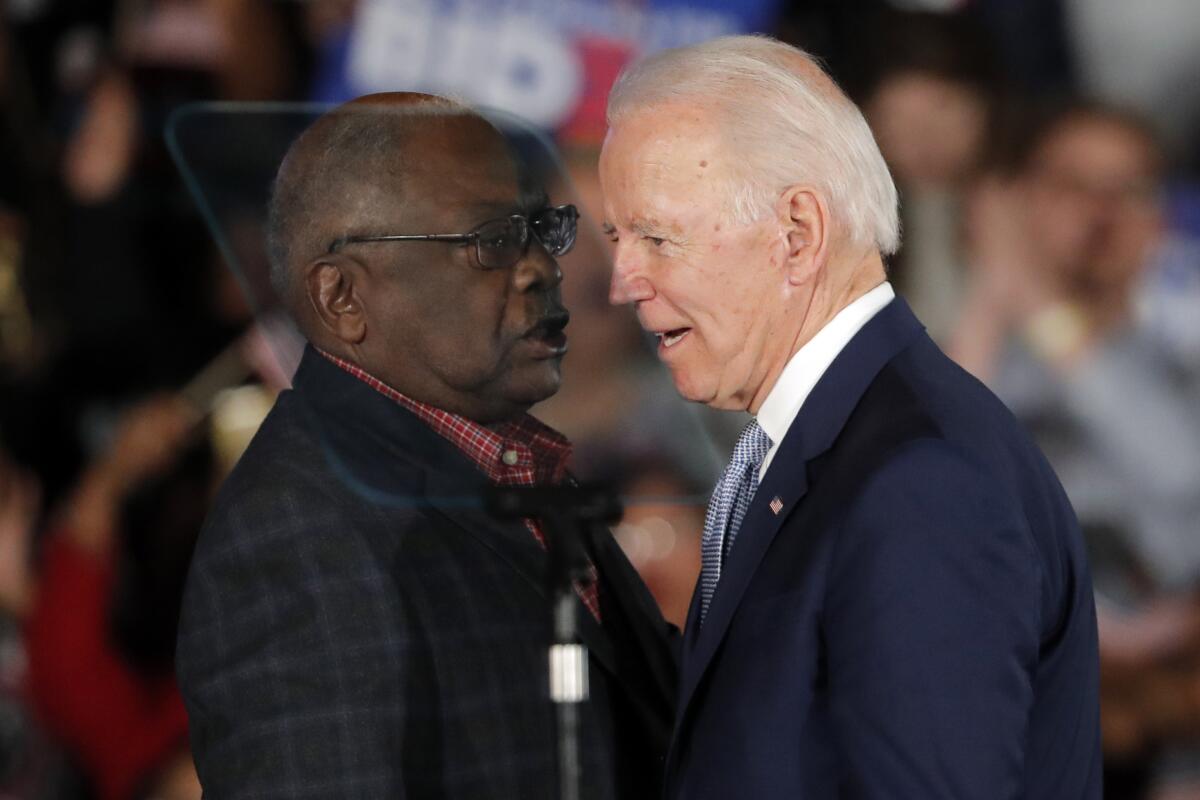

Biden’s pledge was born out of political necessity. During Democratic primaries in early 2020, he rolled into Rutherford’s state as an unexpected underdog. The deep bond he’d forged over decades with Black South Carolinians paid off when he received a last-minute endorsement from the elder statesman of Black Democratic politics there, U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn.

It was Clyburn who introduced Biden, sang his praises and stood by his side during his primary victory speech in Columbia as the candidate tearfully thanked Black voters for having his back and helping him win. And it was Clyburn who coaxed a promise from Biden to nominate a Black woman to the court if he won the presidency.

Justice Breyer’s retirement gives President Biden the chance to fulfill his campaign promise to put the first Black woman on the U.S. Supreme Court.

That sort of loyalty from a key wing of the Democratic base demands much in return, says South Carolina Circuit Court Judge Clifton Newman, another friend of Childs who was also a mentor to her early in her legal career.

The impending retirement of Justice Stephen G. Breyer has given Biden the opening to follow through on his promise. It’s gratifying to see the president keep his word to Clyburn, and by extension, all Black Americans, Newman says.

“For there to have never been an African American woman on the Supreme Court — that’s abysmal,” says Newman, 70, who presided over the state trial of the former white police officer who fatally shot Walter Scott, a Black man, in 2015 in a suburb of Charleston.

“It’s important for there to be an African American woman or man on the court who represents the mainstream of the Black community,” Newman says, turning his attention to conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Newman counts himself among the Black Americans who believe Thomas’ right-leaning political views are out of step with the majority of their community.

As for those who question the qualifications of any of the Black women Biden may be considering, or who think his approach unfairly excludes white prospects, “it’s a blemish on those who have such a closed-minded view,” Newman says.

The 1980 promise was about closing the gender gap, says top campaign strategist.

Vaughn says that she, like many other Black Americans, was raised not to use her race as a crutch in life, but rather to work twice as hard as everyone else just to be seen as equal.

She grew up in Compton and is the daughter of schoolteachers who attended historically Black colleges, then met in graduate school in their home state of Oklahoma.

“Black excellence” was always part of her family’s value system. You were expected to be able to compete with any American so that no employer could claim they were settling for less by choosing you.

“I’m proud that I’m Black,” Vaughn says, “but I’m aware of what that means.”

In her consulting work around the U.S. with the recruiting agency Major, Lindsey & Africa, Vaughn has led countless discussions in which she tries to convey the virtue of building diverse teams at organizations, especially given that Black Americans made up only 2% of partners at the nation’s law firms in 2020, and women just 26%, according the annual Law Firm Diversity Survey.

The first question she asks new clients who are struggling to recruit attorneys from different backgrounds is: “What are you willing to do differently to get a different result?”

The same challenge should be posed to our presidents, Vaughn says.

There have been 115 justices in the Supreme Court’s 232-year history. Only three of them have been people of color, and only five have been women.

“Now back to Biden — he’s willing to do something different to get a different result,” she says. “Whether he can actually pull it off has yet to be seen.

“It’s just unfortunate what these women are going to have to go through,” Vaughn says of the prospect of a racially divisive confirmation battle. “It’s not going to be pretty.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.