20 Western Hemisphere nations sign Los Angeles Declaration on migrants despite key absences

- Share via

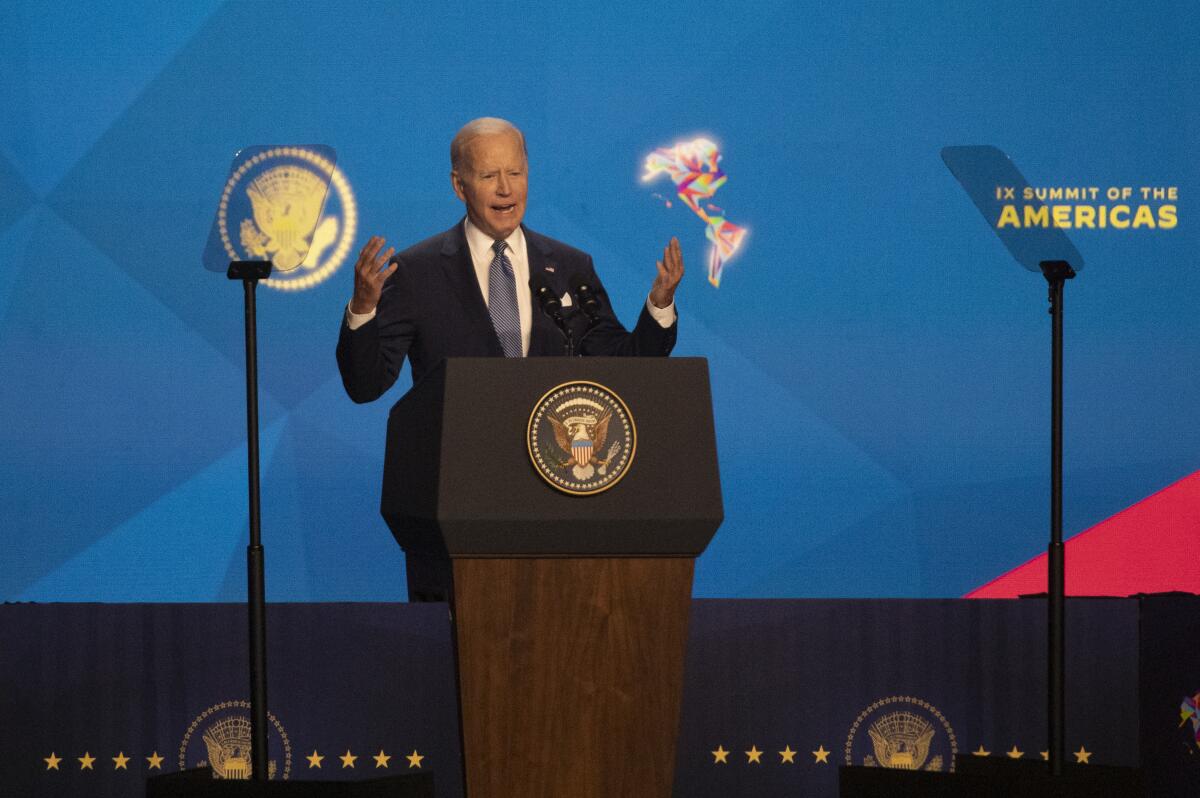

No nation should alone bear the responsibility of managing a historic surge in migration across the Western Hemisphere, President Biden declared Friday as he and 19 of the region’s leaders and their representatives signed a much-anticipated pact to expand legal pathways for migrants and refugees and provide new funding to assist countries in hosting them.

“Each of us is signing up to commitments that recognizes the challenges we all share, and the responsibility that impacts on all of our nations,” Biden said as he joined a group of regional leaders to sign the so-called Los Angeles Declaration.

For the record:

10:37 p.m. June 10, 2022An earlier version of this article said that President Biden and 19 Latin American and Caribbean leaders signed the Los Angeles Declaration on migration. It was signed by Biden and officials from Canada and 18 Latin American and Caribbean nations, in some cases by officials other than their heads of state.

2:20 p.m. June 10, 2022An earlier version of this article stated that Bolivian President Luis Arce publicly criticized the Biden administration’s decision to leave out some leaders from the Summit of the Americas. It was Belize’s Prime Minister John Briceno who criticized the decision.

The signatories to the agreement, announced on the last day of the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles, included Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras — four countries whose commitments were in doubt after their leaders boycotted the conference over the U.S. decision to exclude several countries it considers to be antidemocratic.

Mexico is a key player in the region, and its cooperation is essential to stemming the flow of migrants to the U.S., while the three Northern Triangle nations of Central America — El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras —produce a large share of the region’s migrants.

Though their leaders’ absence had cast doubt on how comprehensive migration talks at the summit would be, Biden administration officials maintained that the pact would include a diverse group of countries coping with the surge in migrants across Latin America.

Migration patterns in the Western Hemisphere have shifted as the region has grappled with a pandemic-fueled economic crisis, exacerbated by political upheaval, violence and environmental disasters. Biden pointed out that millions of migrants who fled Venezuela now make up as much as 10% of Costa Rica’s population.

“[Our] economic futures depend on one another.... And our security is linked in ways that I don’t think most people in my country fully understand — and maybe not in your countries as well,” he said.

The pact includes commitments from Mexico to launch a temporary labor program for 15,000 to 20,000 workers from Guatemala. The country will expand eligibility for that program to include Honduras and El Salvador “in the medium term,” according to a fact sheet provided by the White House.

The Biden administration plans to dole out $314 million in humanitarian aid, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department, as well as provide billions in existing development bank funding to help promote new programs to accept migrants and refugees in countries such as Ecuador and Costa Rica.

The U.S. also will provide H-2B nonagricultural seasonal worker visas to 11,500 nationals of northern Central America and Haiti.

U.S. unwillingness to squarely face migration at this week’s Summit of the Americas in L.A. has turned the issue into the elephant in the room.

Biden also announced stepped-up efforts in conjunction with other countries to combat human smuggling.

“If you prey on desperate and vulnerable migrants for profit, we are coming for you. We are coming after you,” he warned.

Other countries will also be taking steps to address the jump in the number of migrants traveling to the United States. U.S. border officials encountered more than 1.7 million migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border from October 2020 through September 2021, and an additional 1.3 million from October 2021 through April, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Canada, too, will provide $26.9 million for the 2022-23 fiscal year for migration management and humanitarian aid, and Spain is pledging to double the number of labor pathways for Hondurans.

In an email, Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington think tank, characterized the declaration as “a big deal” that “shows how important the issue of migration is to many countries in the Western Hemisphere, not just the United States.”

“If it was just about us, it wouldn’t happen,” she wrote.

But she cautioned about the challenges ahead in working out the details and implementing the declaration’s provisions.

“Our immigration systems are already overtaxed and overburdened — everything from border operations, to [U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’] asylum and legal visa adjudications, to immigration courts, to visa offices abroad, all have serious, record-level backlogs and no end in sight,” Brown wrote. “We must address that for any of this to be workable in the short term.”

Protesters decried the absence of leaders from Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela, Nicaragua and other countries. But some suggest that countries that skipped the summit are hurting their own people.

The declaration caps off a week of meetings among foreign dignitaries, advocates and more than 20 heads of state, who convened in Los Angeles to discuss regional challenges including the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, economic inequality and migration.

Diplomatic cracks over the Biden administration’s decision to exclude the leaders of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela have splintered the summit, which is being held in the U.S. for the first time since its inaugural meeting in Miami in 1994.

On Thursday, the leaders of Belize and Argentina publicly criticized the U.S. decision to leave out some leaders in the region as Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris looked on nearby. Belize’s Prime Minister John Briceño called it “inexcusable” that some leaders were not present.

The migration pact also includes a pledge by the Biden administration to resettle 20,000 refugees from the Americas over the next two years, and a plan to resume in coming months the family reunification parole programs in Cuba and Haiti, which allows U.S. citizens and permanent residents to apply for parole for their family members in those countries.

U.S. unwillingness to squarely face migration at this week’s Summit of the Americas in L.A. has turned the issue into the elephant in the room.

Costa Rica plans to renew a temporary complementary protection program for migrants from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba.

The declaration also commends efforts by Colombia and Ecuador, which have enacted policies to welcome some of the over 6 million Venezuelans who have fled their country in recent years. Colombia pledges to legalize permits for an additional 300,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees by the end of August.

Ecuadorean President Guillermo Lasso, who praised the “political will” of the heads of state and delegations participating in the agreement, said it was important to promote development opportunities in migrants’ and refugees’ countries of origin in addition to assisting the countries receiving them.

Savi Arvey, policy advisor on the migrant rights and justice team at the Women’s Refugee Commission, said that the declaration included some “positive initial steps,” and that advocates are hoping participating countries will follow through on their pledges.

“These are good, initial steps, but as countries work together, we’re hoping for bigger, bolder action, especially on international protection,” she said.

Louis DeSipio, a political science professor at UC Irvine with expertise in immigration, said the declaration’s labeling of migration as a regional challenge and responsibility is important both symbolically and substantively.

It “has the potential to slowly reshape migration patterns in the medium- and long-term future in important ways,” he said.

But DeSipio believes that while the declaration outlines a multilateral, region-wide approach to migration, rather than the bilateral, largely piecemeal strategies of the past, in the short term that will “probably be of little solace to Latin American migrants in the United States and their family members trying to migrate to the U.S.”

“President Biden’s support here is primarily financial, but several Latin American leaders are making substantive contributions by creating new migration opportunities,” DeSipio said. “Over time, if these early efforts are successful … this could create the foundation for more routine labor migration within the Americas, or at least South America.”

Since Biden took office, he has struggled to deal with domestic blowback over a record increase in the number of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. Republicans have seized on the issue to paint him as weak on border security, while progressive Democrats have been frustrated by what they see as a lack of progress in implementing more-humane immigration policies.

Tyler Mattiace, an Americas division researcher with Human Rights Watch who closely followed the declaration’s drafting process, said that this type of multilateral approach is long overdue to assist “the millions of people all across the continent who have fled their homes either because of violence or persecution or human rights abuses.”

“They often face serious abuses that are many times the result of the fact that government either tries to prevent them from seeking protection or make[s] it difficult for them to obtain legal status or implement enforcement strategies to lead to them taking dangerous migration routes where they suffer abuses,” Mattiace said.

He said the declaration is a departure from what’s happening on the ground at the U.S.-Mexico border, where immigration enforcement officials keep expelling asylum seekers under Title 42, a COVID-19-related health measure implemented under former President Trump and maintained by Biden. The measure is tied up in the courts.

“The declaration is a major step forward, but it could be meaningless unless Biden immediately does everything possible to restore access to asylum at the U.S. border and ends other abuses, other anti-immigration policies,” Mattiace continued. “The U.S. also has to stop focusing immigration policy on efforts to outsource immigration enforcement to other governments in the region.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.