California primary’s lesson for pundits: Don’t speak too soon in the age of mail-in voting

- Share via

In the hours after polls closed in the closely watched California primary on June 7, reviews from pundits were quick to come in.

Turnout: abysmal. Progressive reforms: rejected. Ex-Republican Rick Caruso: the surprise star of the night in liberal Los Angeles.

But with the proliferation of mail-in voting, messages from California voters now arrive with a lag — one that hasn’t proved friendly to the quick takes of social media and cable news.

“We used to have a single election day, and often have decisive results for most contests on election night,” said Kim Alexander, president of the nonpartisan California Voter Foundation. “Now, we have election month, and a month of vote counting.”

Reforms making it easier to vote by mail in California have severed the state’s electorate into three distinct tranches: early voters, in-person election day voters, and those who mailed or handed in their ballots on or just before that day, the deadline for postmarks. Ballots from the latter group are often tabulated after election day and new state regulations allow them to arrive up to a week afterward and still be counted, extending wait times for definitive results to come in across the state.

With a pandemic-induced acceleration in mail-in voting, election day results mean less than ever, representing an increasingly small part of the picture.

“It’s been a growing challenge to get the word out before election day to the general public and news media alike to not expect to have definitive results on election night,” Alexander said. “This new ballot flow frustrates the longstanding conventions of how we think about election day and election night.”

Perhaps the most dominant narrative in the media coverage and commentary coming out of election night was that California voters were sending a clear message on public safety and progressive criminal justice reform efforts that could have national reverberations. But in the weeks since California’s primary, some key races across the state have reshuffled or tightened — turning upside-down some of the early punditry about the message Golden State voters are sending this cycle.

“Anybody paying attention to California politics should know that election night results have no bearing on what the final outcome will be because we allow every registered voter to be able to vote, and then we do our best to count every valid ballot cast,” said Ludovic Blain, executive director of the California Donor Table, a progressive fundraising group. “So, it’s really a rookie mistake for people to be doing hot takes the night of or the day after.”

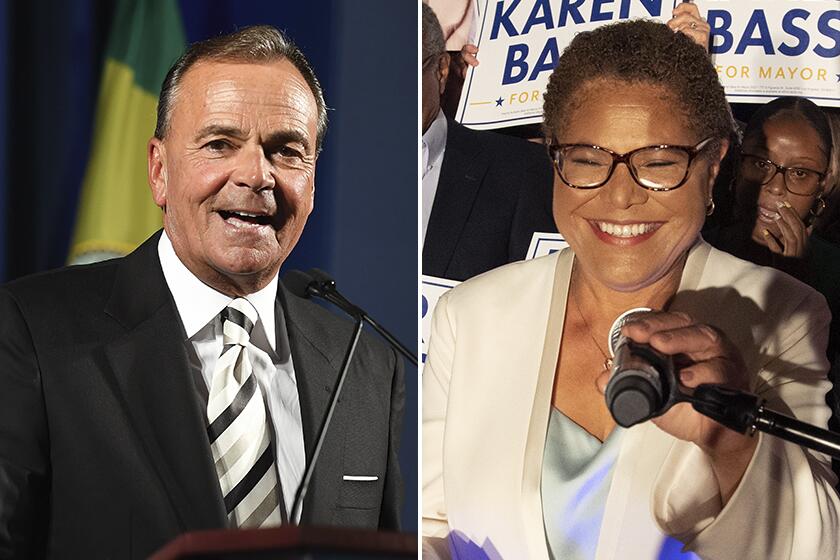

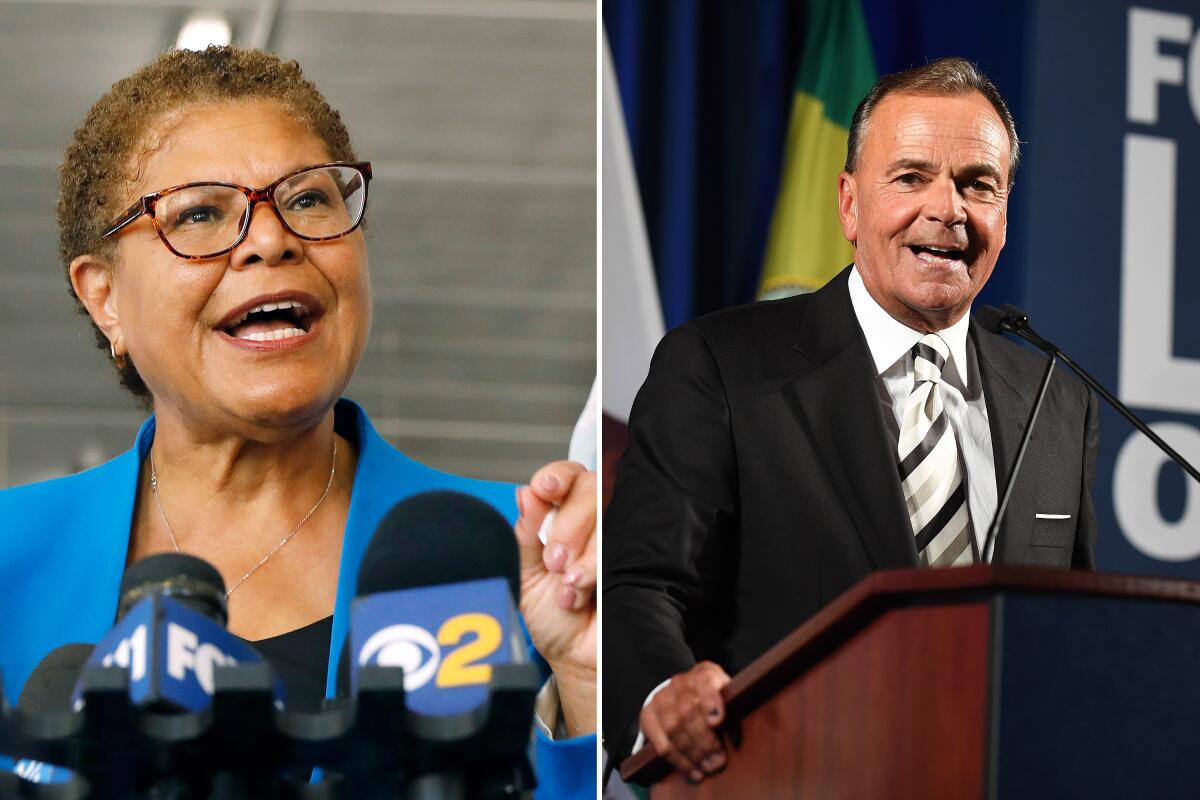

In L.A.’s mayoral race, Caruso, a billionaire developer who ran on a platform of expanding the city’s police force and clearing homeless encampments, celebrated with confetti on election night as he held a five-percentage-point lead over U.S. Rep. Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles), whom he will face in the November runoff.

But just shy of three weeks later, he finds himself trailing Bass by seven points.

The latest count in L.A.’s mayoral primary election has Karen Bass ahead of Rick Caruso, 42.9% to 36.3%.

Bass may have to thank late-deciding progressives who were seeking to assess which of Caruso’s opponents was most viable, said Paul Mitchell, vice president of the consulting firm Political Data Intelligence.

“When the message comes across that it’s a two-person race between Caruso and Bass, those voters get signaled, ‘OK, I guess we’re with Bass,’ and those late votes come in,” Mitchell said.

Mike Madrid, a longtime GOP political consultant, said the late-arriving mail ballots give “a sense of what the waning days of the campaign reflect, as opposed to the conventional wisdom heading into election day.”

“The late vote count tends to reflect the closing sentiment of the elections, regardless of whether it’s a rightward or a leftward shift,” Madrid said.

The late-arriving mail ballots turned the narrative in other races, too. On election night, one of the country’s top progressive prosecutors in one of its most liberal cities, San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin, was losing a recall, 60% to 40%. In the weeks since June 7, the margin in the closely watched recall tightened by 10 percentage points.

Boudin will still lose his job, but progressives say the result shouldn’t be viewed in isolation.

“Voters in San Francisco seemed to vote against Chesa. But in every other opportunity, they voted for reform,” Blain said, pointing to Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s strong performance in the city.

In surrounding Contra Costa and Alameda counties, voters backed a pair of progressive prosecutors, Diana Becton and Pamela Price.

“Chesa’s results have no bearing not only on the country or the state, since it’s just 1/40th of the state, but not even for the Bay, because most voters in the Bay voted for reformers,” Blain said.

Turnout numbers, too, have grown. The figure remains low — just shy of 33% as of Sunday morning, according to state data — but it has risen more than some observers initially expected.

In part, the late surge in turnout may be because likely voters “got their mail ballot and held on to it and returned it on election day,” said Alexander, of the California Voter Foundation.

Still, she says, turnout remains disappointing. It is lower than the previous three June primary elections (including two presidential primaries), and it comes after every voter in the state was mailed a ballot.

But, Mitchell says, the state’s pool of registered voters — the denominator in the voter turnout equation — has grown because of automatic voter registration at the Department of Motor Vehicles and other state reforms. Though turnout as a percentage of registered voters remains low, more people cast a ballot this election than in 2012 or 2014.

The proportion of voters who cast ballots by mail has increased drastically during the pandemic: Almost 87% of California voters in the 2020 general election voted by mail, and while the official breakdown for this year’s primary won’t be available until after the election is certified on July 15, Mitchell estimates that number will be north of 80% again. But the state’s election system has moved slow in order to account for mail-in ballots for several cycles.

In 2018, Republicans lost several U.S. House seats in districts where they initially led on election night. Democrats TJ Cox, Katie Porter, Josh Harder, and Gil Cisneros all pulled ahead of Republican opponents after late votes were counted, despite trailing on election night. In Cox’s race, the Associated Press had to issue a rare retraction after it initially called the race for his Republican opponent, David Valadao, on election night.

The post-election day flips prompted outcry among Republicans — including then-House Speaker Paul Ryan, who called the California election system “bizarre,” saying: “We had a lot of wins that night, and three weeks later we lost basically every contested California race.”

But experts and officials here say the delay simply amounts to the state doing its job by counting every vote.

“We just have to reconcile the fact that if we are going to be a state that is going to make every possible manner of voting available in order to reach people where they are and expand the franchise, we’re going to have to wait,” Madrid said. “And election night is different than the night when you learn the results of the outcomes of the races.”

This year, local officials have until July 8 to report final results to the secretary of state. As the unofficial tallies continue to dribble in, experts say the onus is on candidates, the media and pundits alike to resist jumping to conclusions.

“We’re adjusting to a growing and changing dynamic of vote by mail in California,” said Mindy Romero, the founding director of the University of Southern California’s Center for Inclusive Democracy. “And we just have to continue to be cautious.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.