An earthquake alert system? You bet.

- Share via

A proposed earthquake warning system designed to alert Californians before the forceful seismic waves reach them faces a test this week in the Assembly, where questions about the cost and the technology are giving some lawmakers pause. That’s a good reason for legislators to be careful as they set the project’s parameters, but it’s not an excuse to stop moving forward. A new version of the bill offered by Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Pacoima) makes clear that the system will be a public-private partnership, while giving state officials a year and a half to find the money. The Legislature should approve it.

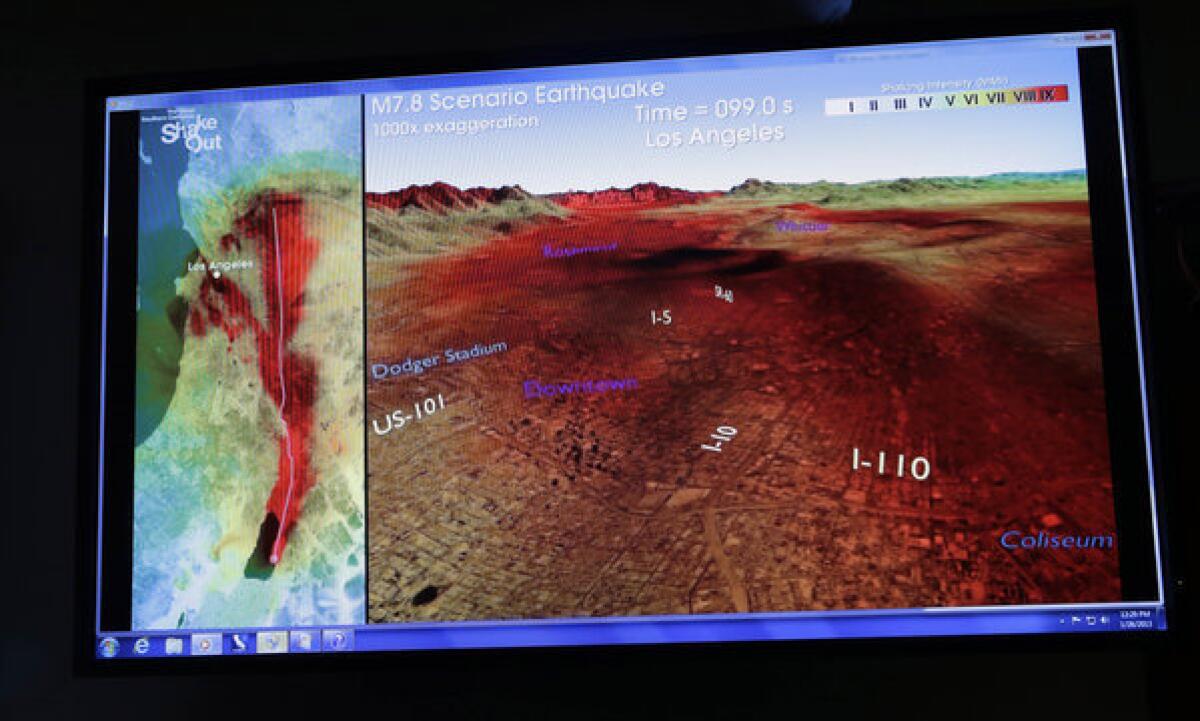

Although scientists can estimate earthquake risks based on the location and seismic history of fault lines, they’ve yet to find a way to predict when a temblor will strike. The system envisioned by Padilla’s bill, like ones currently being used in Japan, Mexico and other quake-prone countries, would send out alerts as soon as sensors detect the first signs of a sizable quake, which happen seconds before the more damaging shock waves reach the surface. For a quake that started in the high desert, Angelenos could be warned 30 seconds or more in advance. Such a system would require a network of sensors along the faults, plus the technology to gauge a quake’s severity, issue an alert and trigger the appropriate responses.

The U.S. Geological Survey has been developing a small-scale system with state officials and seismologists at the California Institute of Technology and UC Berkeley. But the federal government hasn’t put up the money for construction (an estimated $23 million) or operations (roughly$12 million a year). And according to one critic in the private sector — Seismic Warning Systems of Scotts Valley, Calif., which is building its own alert system — a recent demonstration showed that the state’s technology doesn’t work quickly enough to provide any warning to those near a quake’s epicenter.

Padilla’s bill would give the state Office of Emergency Services the ultimate responsibility for developing and managing the system, while leaving the door open for the state to collaborate with private companies that can prove their ability to upgrade the system. That’s the right balance. And as important as it is to reduce the delays that limit the alerts’ utility, such advancements in data crunching can still be achieved after the network of sensors is rolled out.

The Brown administration is exploring ways of funding the system without dipping into the state’s general fund, and that’s welcome. Considering that earthquakes cost the United States more than $5 billion a year on average, however, the investment called for by the Padilla bill is more than reasonable.